"The definition of a gamer is becoming a lot broader and more inclusive, and it might be fair to start calling me one".

Bill Gates has written a new blogpost about a “terrific” novel by Gabrielle Zevin called Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. Titled “This novel about video games felt personal to me,” Gates discusses the book’s plot, some of his own personal gaming history, and uses this lens to muse about his relationships with key Microsoft players.

“I never thought I’d relate to a book about gaming, but I loved Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow,” writes Gates. “Am I a gamer? For a long time, I would have said no because I don’t spend hundreds of hours going deep on one game.

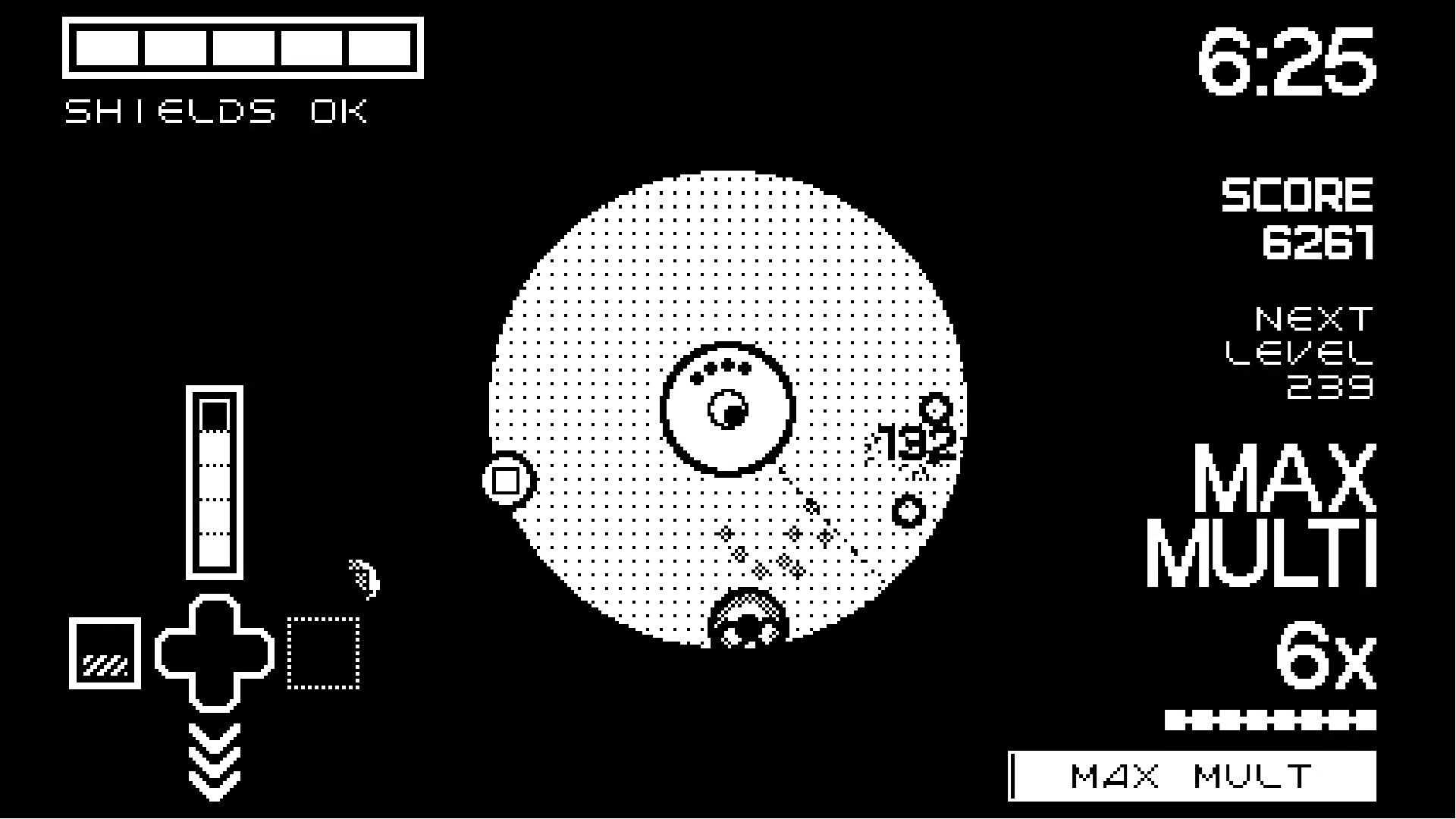

“But when I was younger, I loved arcade games and got very good at Tetris. And in recent years, I have started playing a lot of online bridge and games like Spelling Bee and a bunch of the Wordle variants. The definition of a gamer is becoming a lot broader and more inclusive, and it might be fair to start calling me one”.

I wonder just how good at Tetris qualifies as very good in Gates’ mind, because he’s obviously an exceptional individual and this claim only made me think of a recent Minesweeper story. A former Microsoft employee recalled that, when Minesweeper was being played internally prior to release, Gates got so hooked and was spending so much time on the game that staff had to engineer a high score he couldn’t beat. I half-suspect Bill’s hiding a World of Warcraft habit.

The novel Gates is discussing centres on the life and friendship of Sam and Sadie, who bond as kids over Super Mario Bros. before embarking on a game development career together. “Although there are plenty of video games mentioned in the book—Oregon Trail is a recurring theme—I’d describe it more as a story about partnership and collaboration,” writes Gates. Sam and Sadie create a big indie hit called Ichigo, but the success creates friction and problems in their relationship, with both straining to follow their own path: Gates sums it up as being “about how a creative partnership can be equal parts remarkable and complicated”.

It puts Gates in mind of his own remarkable career, and the friendships and collaborators he had along the way in building one of the world’s biggest software firms. A line in the book says that “true collaborators in this life are rare” and Gates says “I agree, and I was lucky to have one in Paul [Allen]”.

Paul Allen was a childhood friend of Gates, a member of the same computer club, and would later persuade Gates to drop out of Harvard in order to co-found Microsoft. In fact Allen came up with the name of the company, “Micro” from “microcomputer” and “soft” from “software.” Following Microsoft’s enormous success, he and Gates had a troubled relationship in the 1980s and things got a little nasty between them, before the pair patched things up, remaining friends until Allen’s death in 2018.

“An early chapter describing how Sam and Sadie worked until sunrise in a dingy apartment in Cambridge, Massachusetts, could have just as easily been about Paul and me coming up with the idea for Microsoft,” writes Gates. “Like Sam and Sadie, we worked together every day for years. Paul’s vision and contributions to the company were absolutely critical to its success, and then he chose to move on. We had a great relationship, but not without some of the complexities that success brings”.

Gates goes on to muse about one of the questions raised by the character Sadie in the novel, a feeling that the pair’s success is down to timing, to making their game at the right time and in the right era.

“I know what she means: Paul and I were very lucky in terms of our timing with Microsoft,” writes Gates. “We got in when chips were just starting to become powerful but before other people had created established companies”.

Another character in the novel is Marx, who isn’t a creative like Sam and Sadie but has a business savvy and feel for the realities of production that enables the company’s success. Gates calls him “a charming, funny character who you can’t help but root for” and says “If Paul and I were Sam and Sadie, Steve Ballmer was our Marx”.

Steve Ballmer joined Microsoft in 1980 as the 30th employee, and was the company’s first ever business manager. Ballmer had first met Gates at Harvard, where they had rooms in the same hall, and was with the company in various senior roles including president until he replaced Gates as CEO in 2000, a role he held until his departure in 2014. Ballmer and Gates are said to have had an incredibly close relationship, one Ballmer described as “brotherly” in 2016, but plenty of head-butting too, particularly in later years. In the same 2016 interview Ballmer said he and Gates had “drifted apart” ever since Ballmer resigned as CEO.

“[Steve Ballmer] didn’t write code, but the success of Microsoft was highly dependent on him,” writes Gates. “Like Marx, Steve made sure we hired the right people and had the tools we needed for the company to take off. The comparison isn’t perfect: We always appreciated Steve’s value, but in the book, Sam comes to resent Marx and downplays his contributions. (And of course Steve became Microsoft’s CEO, a position that Marx never reaches at Unfair Games.) But Zevin understands that dreamers alone can’t turn big ideas into reality—you need doers, too”.

Gates ends with a hearty recommendation for Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and says video games and the industry around them “is a terrific metaphor for human connection. As Zevin writes, ‘To allow yourself to play with another person is no small risk. It means allowing yourself to be open, to be exposed, to be hurt. To play requires trust and love.'”