One level designer’s journey from quality assurance to independent, and decidedly weird, worldbuilding.

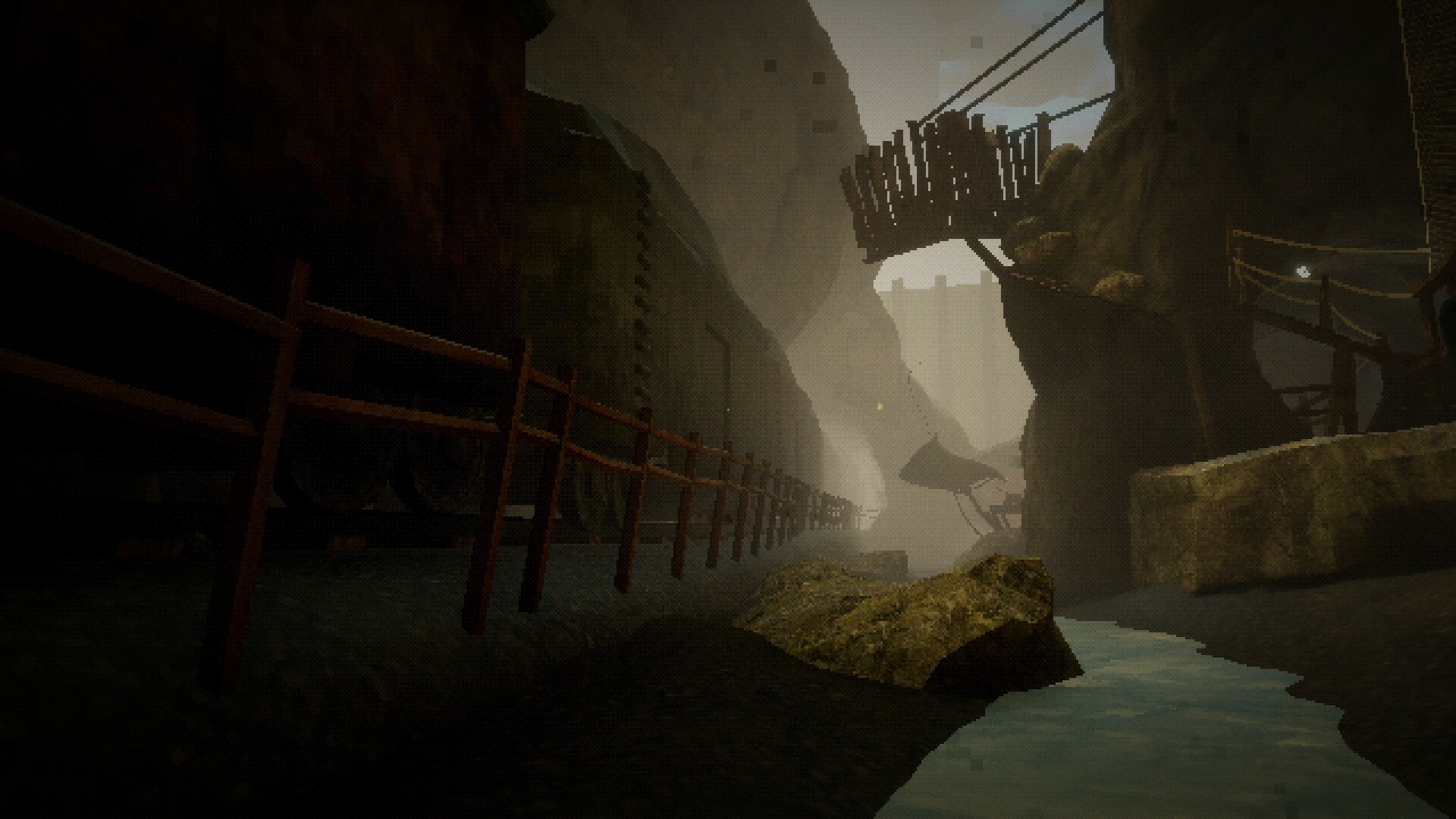

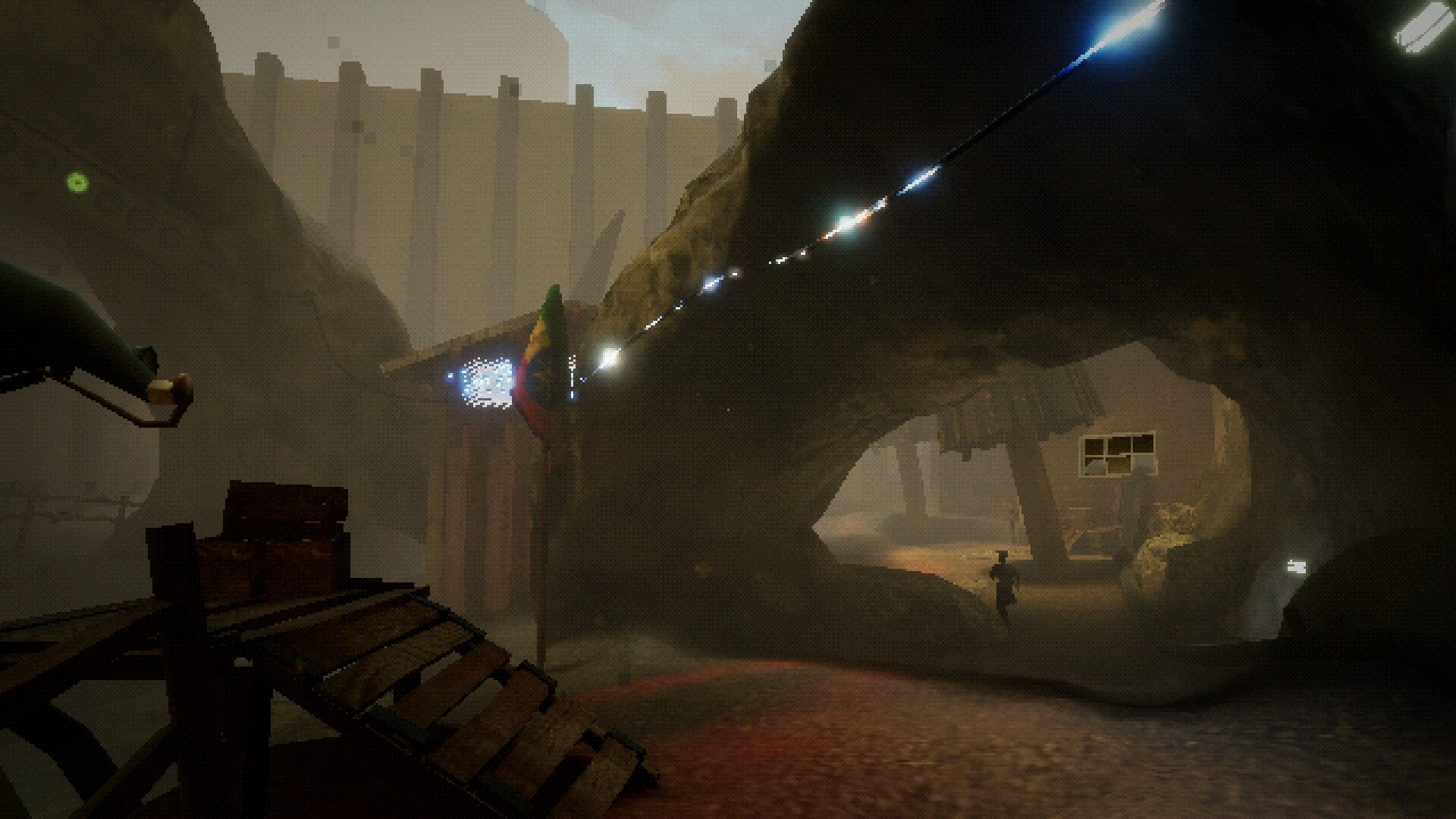

The clerks who work on the side of Mount Zugspitze enjoy free dental care. But it’s less a perk and more an apology, for what the job will do to your teeth.

Clerking is, somewhat unexpectedly, an outdoor role—and up here, the air is thin. You’re best advised to save your breath, walking slowly and deliberately, and jumping only when absolutely necessary. Because sooner or later, you’ll run short of oxygen, and when you do, you’ll need to bite down on a canister—breaking the glass and releasing that sweet, life-giving high directly into your mouth. Your clerk grunts in pain as his molars push against the brittle cylinder, until it cracks. Suddenly, he’s spitting blood and shards from between his lips. “We get used to it,” says your line manager, Mo. Only he doesn’t say it—he writes the message on a scrap of paper. Another breath saved.

Your purpose is clear: the freight train must run. An unending chain of carriages passes behind an imposing border wall, and it’s your job to ensure the locomotive meets its expected pace. Ironically enough, everything that matters is operated by whistle: the elevator that brings Mo to your station, the door to the eerie shack where you speak to your superiors—even the speaker that signals to the train’s unseen engineer, and is answered with a burst of flame from the locomotive’s furnace. All require deep, hard blasts of breath that leave you lightheaded and desperate for more O2.

Air canisters are paid for with tickets, which are earned by keeping the pace and cleaning the cack-covered filters of the stream that runs beneath the wall. As you feed yet another ticket into the machine that keeps you breathing, you might well wonder whether your employers designed it this way—incentivising hard work through a dependence on the bare minimum needed to survive.

This is Threshold, the striking indie horror game from French designer Julien Eveillé. Often, knowing Eveillé’s background at Arkane, it puts me in mind of Dishonored. This must be what it’s like to work on a whaling trawler, or on the factory floor, in the overindustrialised city of Dunwall—rather than pinging between the rooftops as a supernatural assassin.

Eveillé first joined the Dishonored 2 team in quality assurance, before working his way onto the level design team for its follow-up, Death of the Outsider. “I started making maps in my spare time,” he says. “And I sent one or two to the lead level designers.” A few weeks later, they pulled Eveillé into a room to offer him feedback. “For five minutes they told me everything that was good with it,” he says. “And then for 30 minutes they told me everything that wasn’t really good with it.” But Arkane’s master level designers, the ones who build those gorgeous warrens riddled with interconnected routes and intriguing paths, recognised that Eveillé had potential. They gave him a chance.

My architectural skills were a bit absurd to some degree.

Julien Eveillé

“My architectural skills were a bit absurd to some degree,” he says. “Not everything was making a lot of sense in the way it was structured.” It’s this spatial sense that defines Arkane’s revered style of level design—the idea that a building should be structured in a way that feels natural and functional. If there’s a dining room, there ought to be a kitchen. If there’s a bed, there ought to be a bathroom. “Making everything quite consistent helps with going deep in the immersion,” Eveillé says. “You feel like you are part of the world. And I think that power fantasies work even better in that way, if you feel like the world is credible, and you’re in control of cool powers in some place that feels real.”

Eveillé worked on Death of the Outsider’s revamp of the Royal Conservatory from Dishonored 2—a nest of witches that was now in the process of being purged by puritanical Overseers. “That was cool for a junior level designer, because I could grab something that was already done at first and just refurbish the space,” he says. “Try to change the layouts and pacing but not make something from scratch entirely. That was nice to practice and get going.”

Afterwards, Eveillé moved onto Wolfenstein: Youngblood, where Arkane Lyon collaborated with the custodians of the classic shooter series in Uppsala, Sweden. “We at Arkane were mainly focusing on the streets of Paris,” he says, “and MachineGames was on the interiors, the big towers. They were taking care of that part.” Arkane Lyon had history with Paris, which was intended to be the setting of its legendary cancelled project The Crossing. But bringing the studio’s style of vertical, weaving level design to the French capital was no easy feat.

“Paris is mainly Haussmann architecture,” Eveillé says. “Very simple, big walls. It’s too high, basically.” That’s unlike Dishonored’s riff on Victorian London, with its many different rooftops of varying height, perfect for parkour. “We had to find solutions for that,” Eveillé says. “It’s a lot of big avenues, but you can go in apartments, and we made sure to exploit balconies as much as possible.” The introduction of a double jump helped. “Because it’s kind of a constraint actually, Paris, when you are not that mobile,” Eveillé says. “You’re not Spider-Man or anything.”

From there, the only way was Updaam. Eveillé worked next on Deathloop’s cliffside town map—home to Blackreef’s library, Dorsey Manor, and the LARP castle of Charlie Montague. Not only was the level brimming with assassination targets and opportunities to sabotage NPC parties, it had to double as a deathmatch location for player invasions.

“There was this idea of having some sort of an invasion system, like the Souls games, from I think the beginning,” Eveillé says. “So we had time to think it through. It mainly drove the fact that levels are a bit more open. They are less of a corridor, with a lot of options at any time, no matter the tools you have in your skill set, to be able to tackle every situation, or have a way to escape when you’re in a dangerous place.” Some buildings, like Updaam’s library, were opened up during online showdowns for the sake of mobility—so that players had shortcuts available to them. “It was in the air, so we had to think about it every time we made a decision.”

Deathloop was an odd game to work on—a smaller-scale experiment that grew in scope after it was announced, and launched to huge critical acclaim. “It wasn’t an easy project to do,” Eveillé says. “There was a lot of uncertainty. I recall that it was a bit tough. But we were nicely surprised about the reception. It was a cool moment.”

Today, Eveillé works at Crytek, as a designer on Hunt: Showdown. But he’s managed to make and release Threshold in his spare time, and sees the influence of his old employer in the reliable consistency of its strange, unique world. The bucket that can be used to clear mysterious white matter from the stream’s filters, which also works just as well when digging up a grave.

“If you put too much gravel in the machine, at some point, it will just break,” Eveillé says. “You can kind of soft lock yourself that way, but that’s intended—if you fucked up too often, that’s on you. And I think that comes a bit from Arkane. ‘I’m told I can use a tool in that way, but what if I try other things? What if I find cool new things to do with that?'”

You might say it’s design with teeth. For as long as we have any left in our heads, anyway.