Is asking not to sell data the same as asking not to track it?

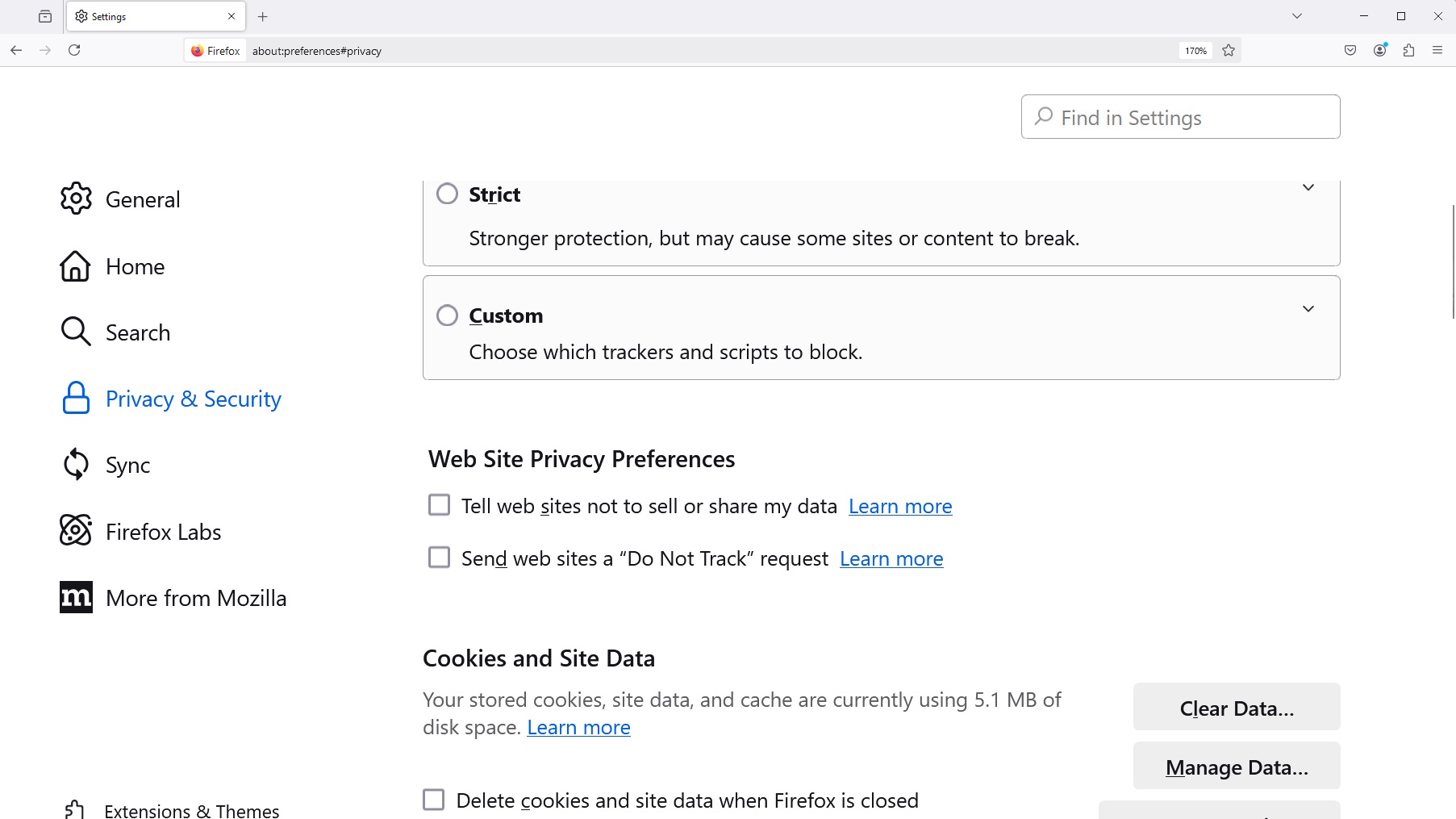

Anyone else feel like the past decade has been one of the gradual normalisation of privacy-defiling practices? If so, you’ll be saddened to hear that Mozilla is binning the ‘Do Not Track’ (DNT) privacy option in version 135 of Firefox. It’s already gone in the Nightly developer release and it should be gone from the standard release on February 4, 2025, when 135 launches.

The Mozilla Do Not Track support page states (via The Register): “Starting in Firefox version 135, the ‘Do Not Track’ checkbox will be removed. Many sites do not respect this indication of a person’s privacy preferences, and, in some cases, it can reduce privacy.

“If you wish to ask websites to respect your privacy, you can use the ‘Tell websites not to sell or share my data’ setting. This option is built on top of the Global Privacy Control (GPC). GPC is respected by increasing numbers of sites and enforced with legislation in some regions.”

This might initially sound like not such a bad thing, the way Mozilla talks about it. But it is, in my opinion, part of a broader trend to bait and switch general privacy concerns for more specific ones. Let me explain.

DNT is a request header that asks sites you visit—you guessed it—not to track you. Websites can then decide whether to adhere to this request, but the idea is to make it so users can easily signal to sites their privacy preferences without having to set these preferences for every site. Whether sites have to adhere to these requests would then be a legal matter depending on the laws in different regions and so on.

While it’s true that most sites simply ignore these requests, I’d argue that’s a legal or enforcement issue and not an issue with the DNT request specification itself. This is in the same way that there’s nothing wrong with requesting people don’t punch you in the face. Even if people keep ignoring that request and get away with it, the request itself is reasonable, don’t you think?

The argument, or at least the implication, seems to be that we shouldn’t worry because Global Privacy Control (GPC) is the new replacement for DNT, and it’s better respected by websites and sometimes actually enforced.

This might be true, but seemingly buried in the small print is the crucial fact that GPC doesn’t as sites to stop tracking you like DNT does. It asks them to stop selling the data that it does track. Its specification refers to “do-not-sell-or-share” interactions or preferences, not do-not-track ones. Bait and switch, much?

This is, of course, better than nothing. And it’s perfectly fine for those who were only concerned about their data being sold. But I’d bet that at least some users who were keen on DNT didn’t want their data to be tracked at all, in principle—at least not by default. It’s not just that users might want privacy in the relation between themselves and the site in question, protecting information from outside sources. It’s that they might want privacy full-stop, including from whichever website they’re visiting.

Best gaming mouse: the top rodents for gaming

Best gaming keyboard: your PC’s best friend…

Best gaming headset: don’t ignore in-game audio

Plus, opening the door to “tracking, but not selling” could still mean companies you aren’t aware of accessing your data, because a website might not sell your data but might give it to a partnered company, for example. The corporate world is wild, and you can bet if there’s a way around things, some companies will find it.

It’s not as if DNT was in principle unenforceable, either. Only last year a German court ruled that LinkedIn had to listen to DNT requests.

Whether the trend towards swapping out general privacy concerns for more provincial ones is a sign of people throwing in the towel on general privacy because it’s difficult to enforce, or whether it’s people and companies actively deciding to allow companies to continue to guzzle our data, it doesn’t matter. The result is a continued normalisation of privacy erosion.

Of course, Mozilla might not intend any of this, and it might just be a “well, what’s the point anyway?” response to DNT not being taken up by websites and courts at large. But I can’t help but wonder: Why bother removing the setting instead of having it as an additional option? GPC and DNT request headers could both exist side-by-side.

One might argue that a DNT setting could mislead users into thinking that their activities aren’t being tracked when actually it depends on the website adhering to the request. But surely that’s something a simple warning could fix. And at any rate, the same would be true of GPC.

Mozilla was the first to implement DNT, so it’ll be particularly sad to see the option disappear from Firefox for that reason, too. Here’s hoping something better comes along, something which is legally binding and easily enforceable. I won’t hold my breath, though.