Always the same. Always different.

If there’s one game everyone—and I mean almost literally everyone—has played, it’s Tetris. It’s on every digital device going. We all end up with at least one copy even if we don’t remember buying it, the gaming equivalent of a Queen’s Greatest Hits CD that somehow, some way ends up on your shelf. There are at least four different versions of it in the room I’m sitting in right now, and almost certainly as many in another.

Which made Tetris Forever, a collection of more than a dozen versions of Tetris out now on Steam from the ’80s and ’90s, sound a bit redundant to me. Tetris isn’t gaming history; at least not in the traditional sense of being old and done with and needing to be preserved lest we all forget about it. The game is so big it’s part of all of our lives. Tetris is vibrantly alive. I’ve already played several of the games contained in this collection, and I managed that just by existing in the ’90s. Heck, I still own one of them on its original cartridge.

And the rest? Well, they’re just more Tetris, aren’t they?

What I was missing was the context Forever’s playable timeline provides. Playing the original Electronika 60 version of the game (the Soviet-era PC Alexey Pajitnov created Tetris on), with its monochrome display and pieces crudely made out of square brackets, really brought home just how quickly—instantaneously, really—Tetris came together. Not as a brand or even as an entertaining game, but as a timeless puzzle concept.

Without wishing to diminish Pajitnov’s astounding work, Tetris feels less like something invented and more like something that naturally emerges whenever people are found, like fire and basket weaving.

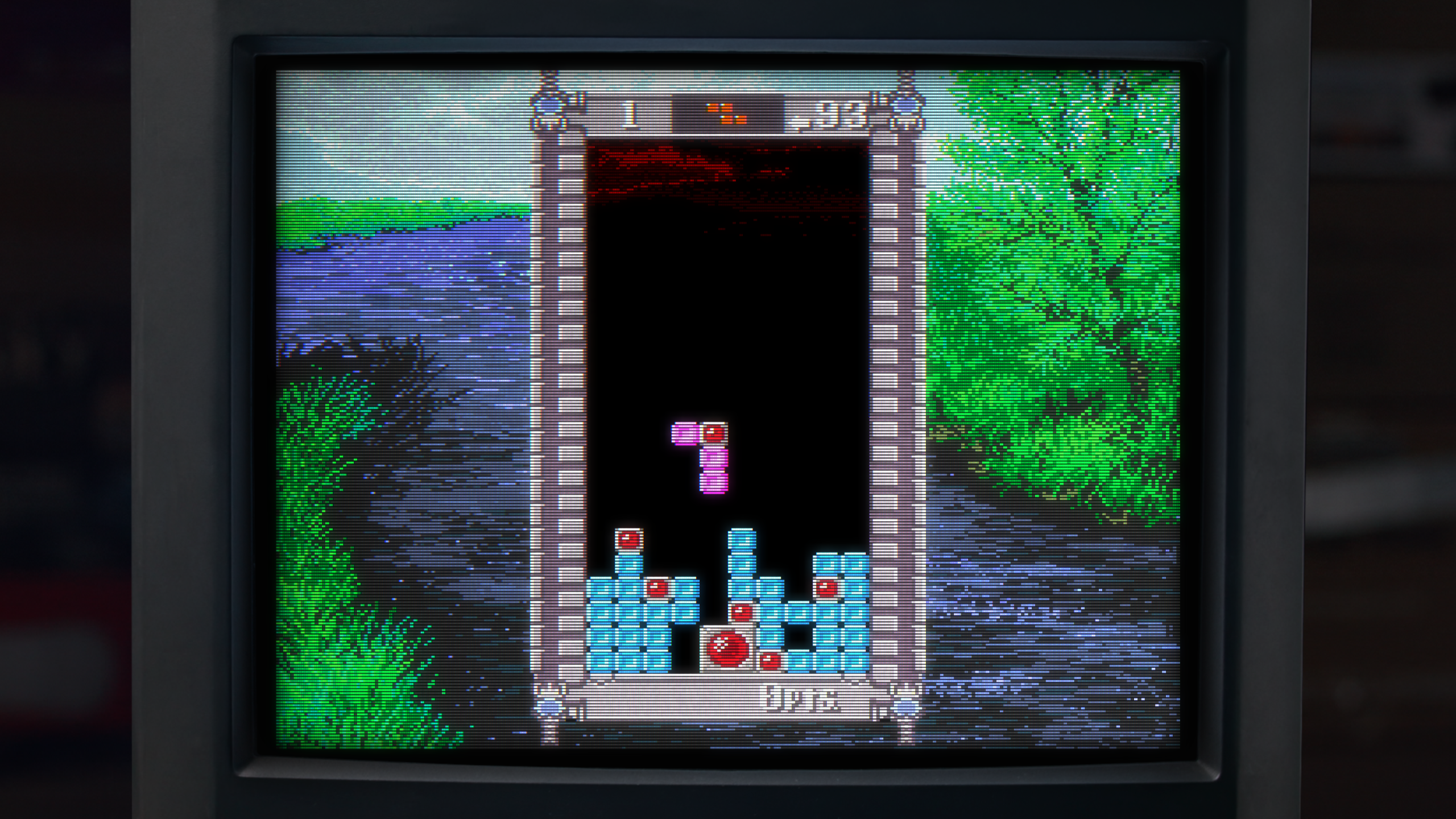

There’s something almost primal about it. The seven shapes are always instantly recognisable, whether rendered in soft SNES tones, fuzzy Apple colour, or the crisp lines found in the more modern versions of the game. It’s easily understood within moments—of course the falling blocks need to be neatly arranged, what else would I do with them? Slotting the long “I” block into place and clearing four lines at once will forever be one of the simplest yet most satisfying actions ever committed to code. But further time spent with Forever’s collection, where DOS games with ASCII borders rub shoulders with cute SNES titles, reveals just how diverse and malleable this apparently unchangeable game is—and actually always has been.

The rules the game’s iconic tetriminos abide by change often and without warning. Being able to rotate clockwise and anticlockwise feels like a standard ability (and it certainly helps a lot when the game picks up speed) but hasn’t always been a feature. Hard drops—that’s when the current piece instantly snaps to the ground—used to be the only way to force a tetrimino down to the ground until it suddenly wasn’t available at all, and then came back later. Being able to slide pieces along the bottom for a short while before they “set” isn’t a universal feature either, but it did debut earlier than I’d imagined—in the Famicom’s Tetris 2+Bombliss, at least as far as this collection’s concerned.

Even the number of players fluctuated. Tetris Battle Gaiden generally plays a lot like recognisably “ordinary” modern Tetris apart from the ninjas, pink bunny creatures, princesses and the special skills they can use to cause trouble for the game’s mandatory second player. Super Tetris 3’s “Familiss” mode allowed four players to puzzle it out at once.

Like Tetris Forever’s approach to interactive history? Check out our feature on its previous game:

The Making of Karateka proves the best way to tell gaming history is with a game, and the rest of the industry must follow its lead

All of this is without mentioning the really odd parts of the series’ history when it wandered off to be Hatris—a hat-stacking game—for a bit, or the time it pondered whether what Tetris’ formula had been missing all along was screen-clearing explosives and new shapes.

Tetris’s presentation shifted just as freely, changing with the era, the gamers the developers hoped to entice, and even the sort of mood they wanted their version of the game to convey. Many of the earlier games lean hard into the Russia-flavoured advertising of the time (“The Soviet Challenge”, as the DOS/Apple II box says), and make the effort to show space scenes, hockey matches, and of course the iconic form of Saint Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow. In context it’s striking and “worldly”, almost as if this brand-new game was so strange and special it had to be imported from another country.

And then Tetris 2+Bombliss comes along and couldn’t be more different. This little NES game looks comfortable, welcoming, soothing. The Tetris side of it goes for a homely look with a cute wallpaper-effect background and a nice pot plant on the screen just for good measure. Bombliss takes its players on a fantasy world tour, starting in space but soon moving on to castles nestled in rolling green countryside and casual coffee dates by the Arc de Triomphe. To ask if it’s better or worse than any of the others is missing the point, because this Tetris isn’t interested in competing at all. This is Tetris made for a casual evening, Tetris with nothing to prove.

Tetris Forever’s curated selection of experiences show this primal creation’s true strength over and over again, and I was surprised to realise that greatness wasn’t as closely tied to the minutiae of block-tidying as I’d previously assumed. Fussing over wall kicks and T-spins is all well and good, but Tetris is really at its best when it’s trying to capture a feeling.

It can be cozy, like Tetris 2.

It can be a chaotic tetrimino-stealing scrum, like Battle Gaiden.

It can be an awe-inspiring home theatre experience like Tetris Effect, a simple thing played on a battered old Game Boy in the park, or anything in between.

It is always bigger and more important than any rules, and will not just survive but thrive whenever it tries to connect with the people playing it, wherever and whenever it finds them.

Forever, even.