What I learned from a visual novel about debating undead philosophers.

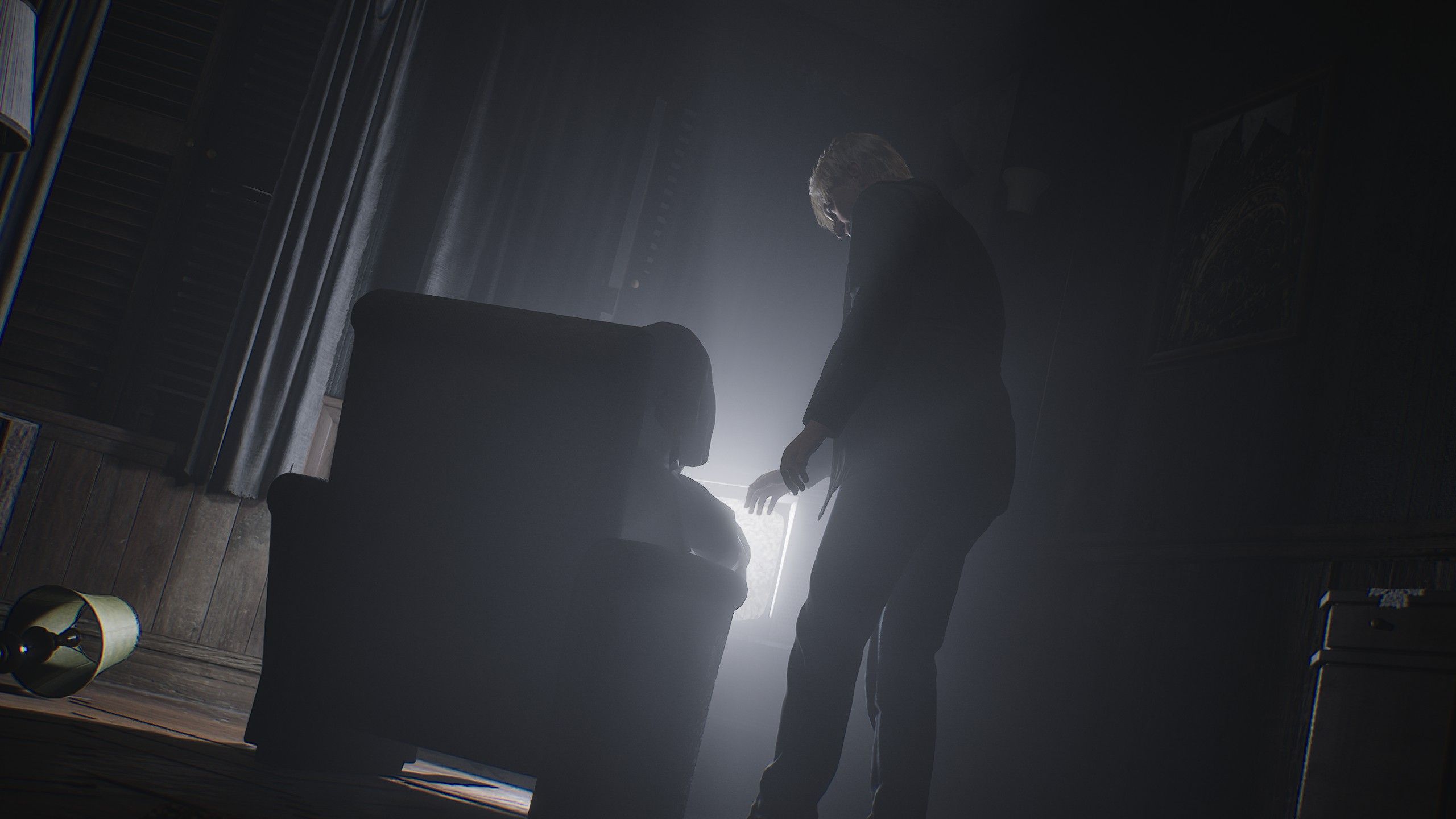

Ariadne Jones is having the worst night. Her mom’s on TV campaigning for reelection, and she doesn’t need any reminders of their strained relationship. There’s a loud party downstairs her roommate really thinks it’d be good for her to go to, but she’s an introverted nerd and she has a test tomorrow she can’t study for because of… everything else.

And now she’s just so tired she’s falling asleep, which means she’s gonna wake up in the Intelligible Realm—an afterlife full of dead philosophers. It’s a long story.

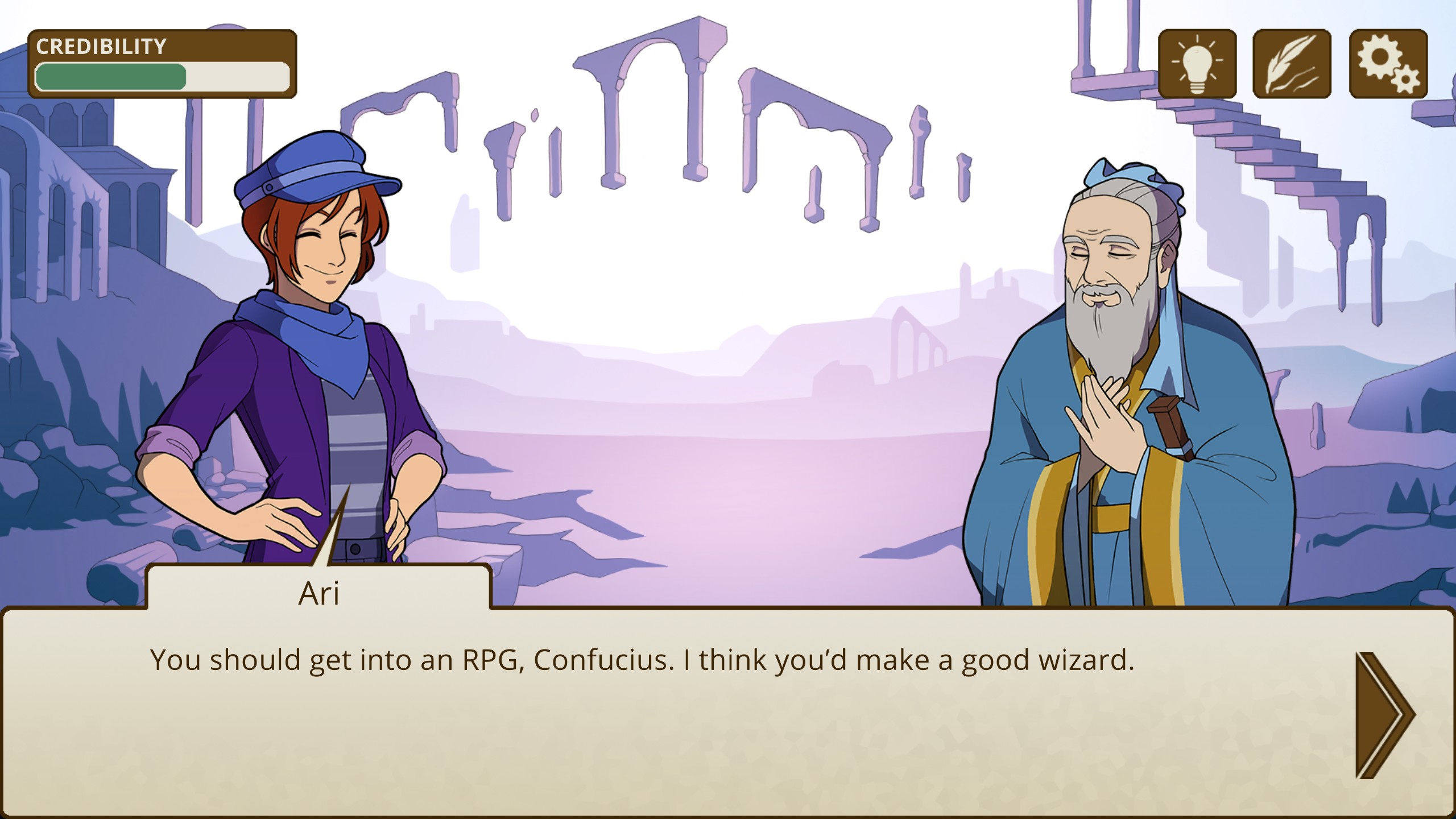

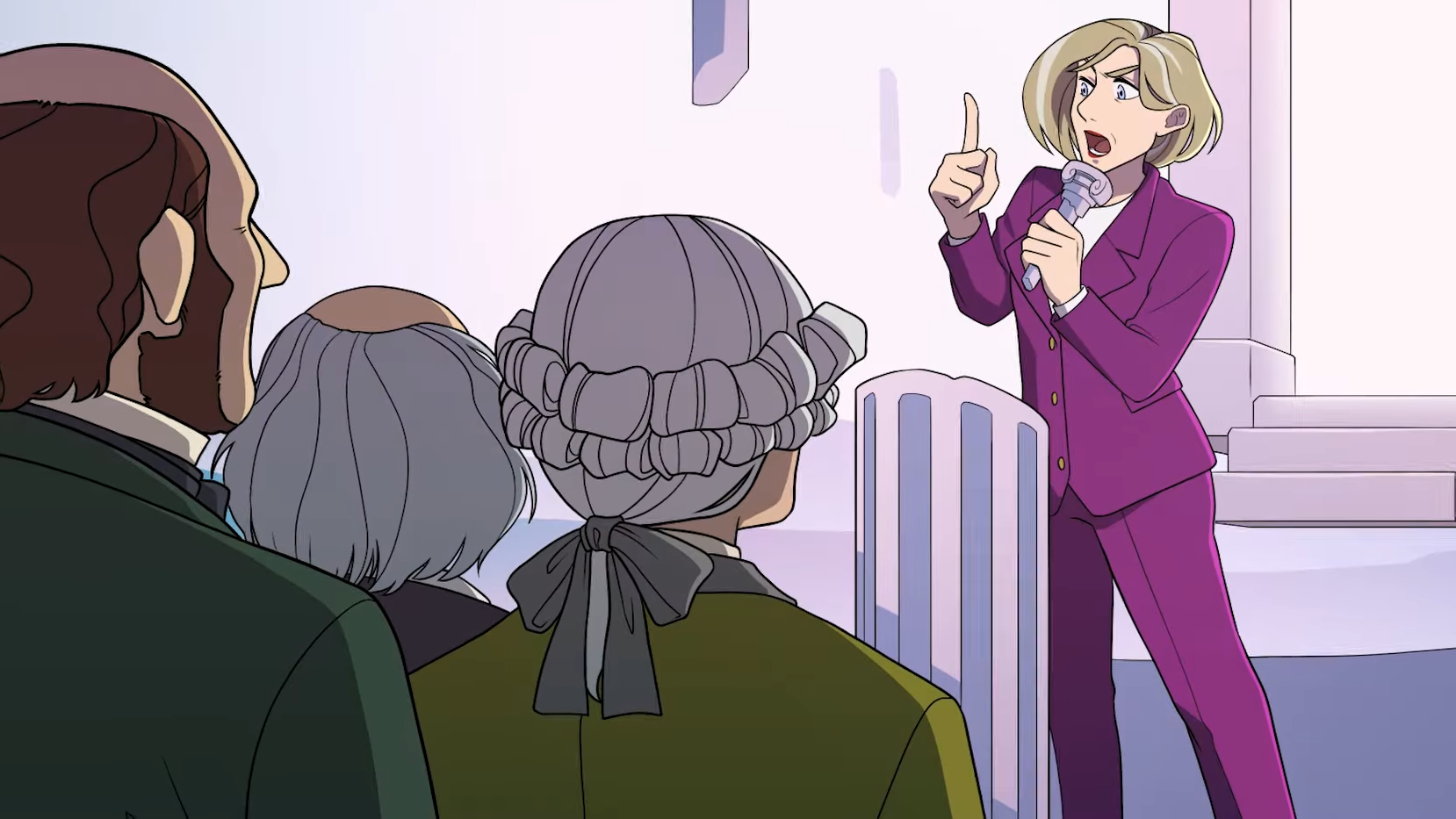

Developed by Seattle-based Intelligible Games—a self described “nights-and-weekends” studio of Riot, Bungie, and ArenaNet veterans—Pro Philosopher 2 is a follow up to 2013’s Socrates Jones: Pro Philosopher. Mechanically identical with an updated art style that has matured from webcomic to visual novel status, the sequel is about Ari’s journey through the “philosophical afterlife” to save her (maybe dead?) mom ahead of her reelection, where she must debate her way through great political thinkers from Confucius to Nozick who have shaped society through centuries of galaxy brain ideas. Along the way she has to find an answer to the ideal form of government and convince her mom that—like liberal democracy—she’s not perfect, actually, but also that’s okay.

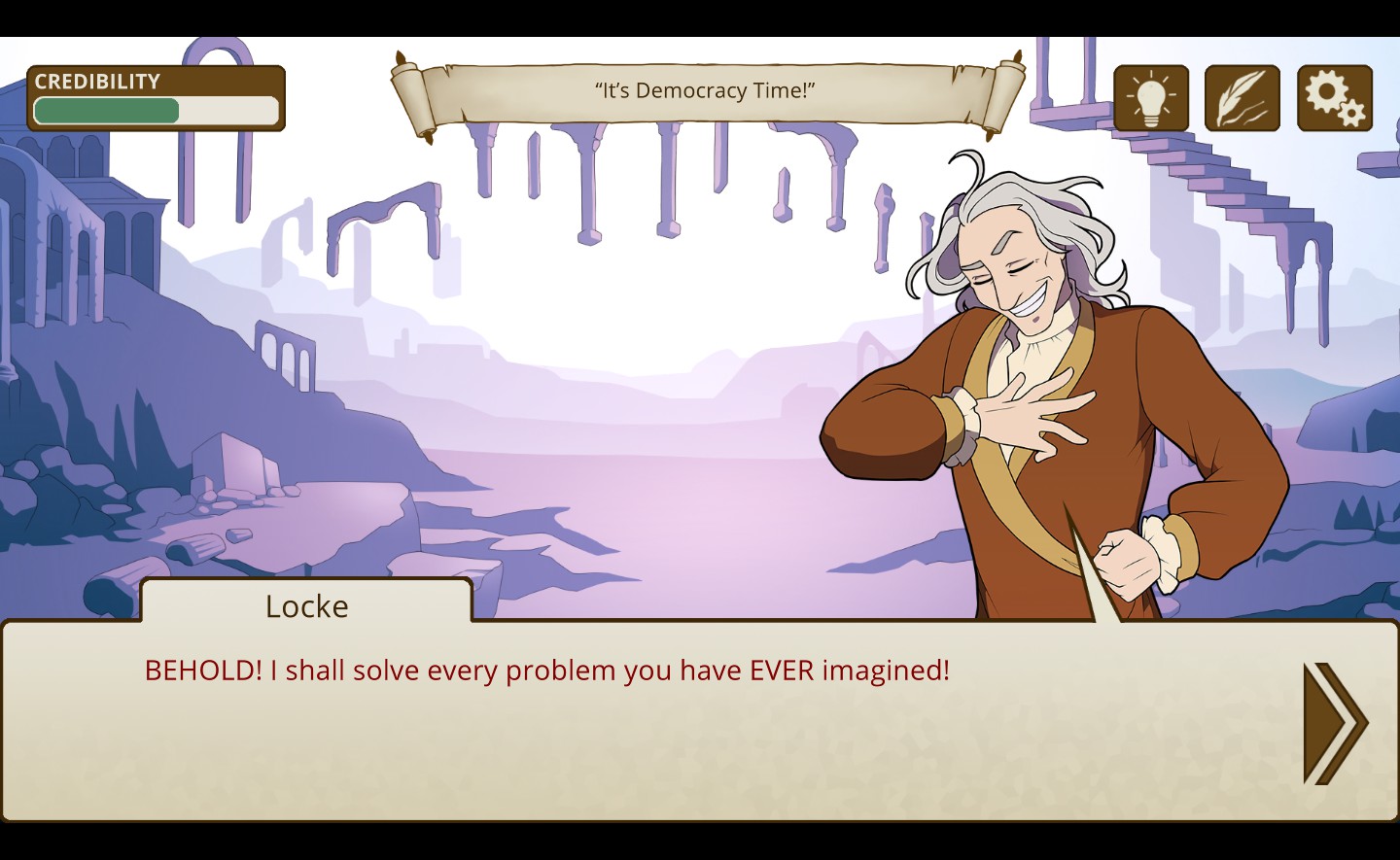

It’s an outrageous premise that’s executed artfully. From the anime-esque caricatures of its cast of philosophers (picture John Locke with Bishie sparkles) to contemporary memes (not just Hamilton references, but those too) to the comedic voice and personality that matches each philosopher’s vision, the game remains humorous and lighthearted by avoiding anything too specific as to be a sore spot for American players dealing with their own election season anxiety. The problems are all general issues we’d recognize from any nostalgic era of politics past.

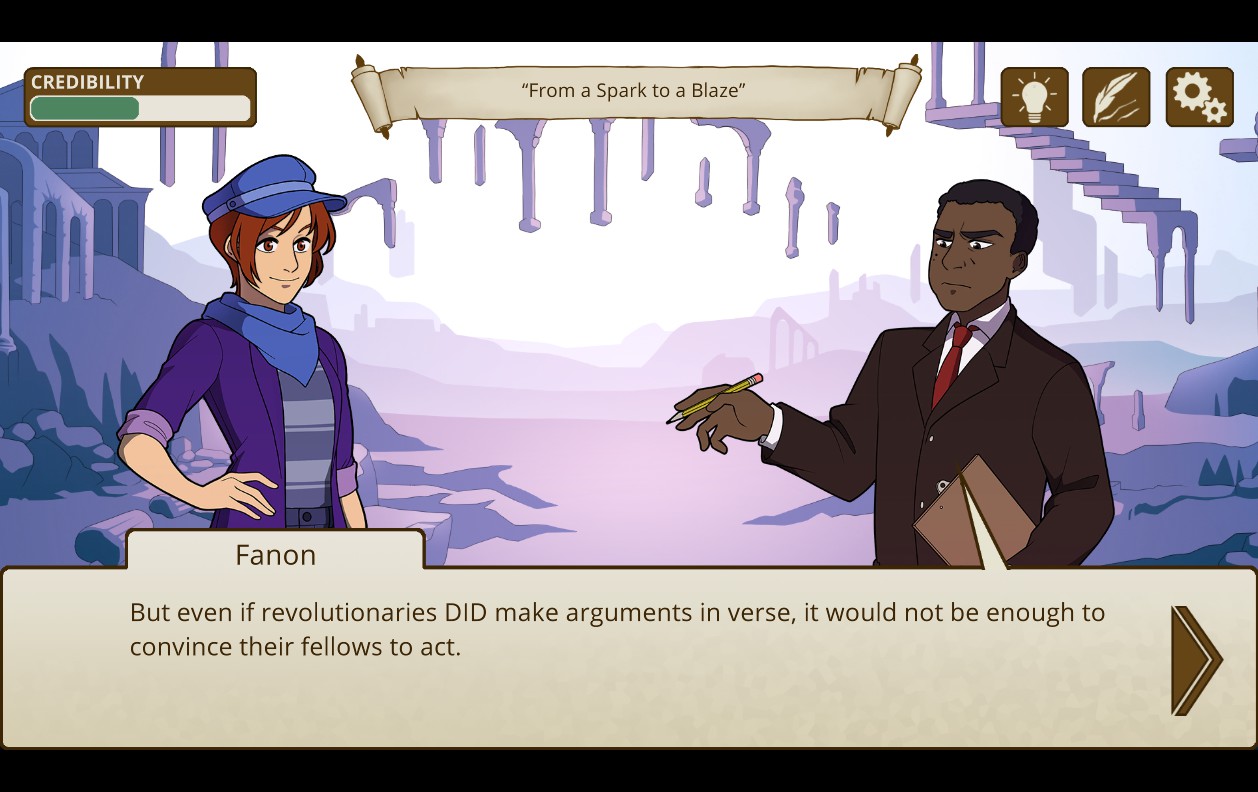

Pro Philosopher 2 shares more in common with deduction-based visual novels like Ace Attorney than the collegiate sport the most obnoxious men you know did in undergrad. Play consists of asking questions and finding challenges to the premises of your opponents’ arguments. Knowing all your fallacies will help, but really you just need to follow the line of reasoning and see where it snags—an assumption, a leap, a tangent, a knot that needs to be unwound and then challenged piece by piece.

Debates are won by proving your opponent’s logic unsound, finding the contradiction in an ostensibly perfect system rather than somehow proving them bad or wrong. Ari’s takedown of Machiavelli’s tyranny is not rooted in why torturing your political opponents is, like, bad, but in how it’s an unstable framework that cannot ever actually provide the stability its promises. Similarly, you can beat Fanon in an argument by teasing out the ways in which his philosophy may fail to establish a stable post-revolutionary government.

So, what did I learn from playing a visual novel about political philosophy in the weeks before the third straight “most important election of my lifetime?”

I certainly learned some specific terms and names I hadn’t ever read directly in intro to philosophy or my history courses, but what’s more important is the game’s lesson that as much as we rely on the past, perhaps no system is truly comprehensive or applicable to every historic moment.

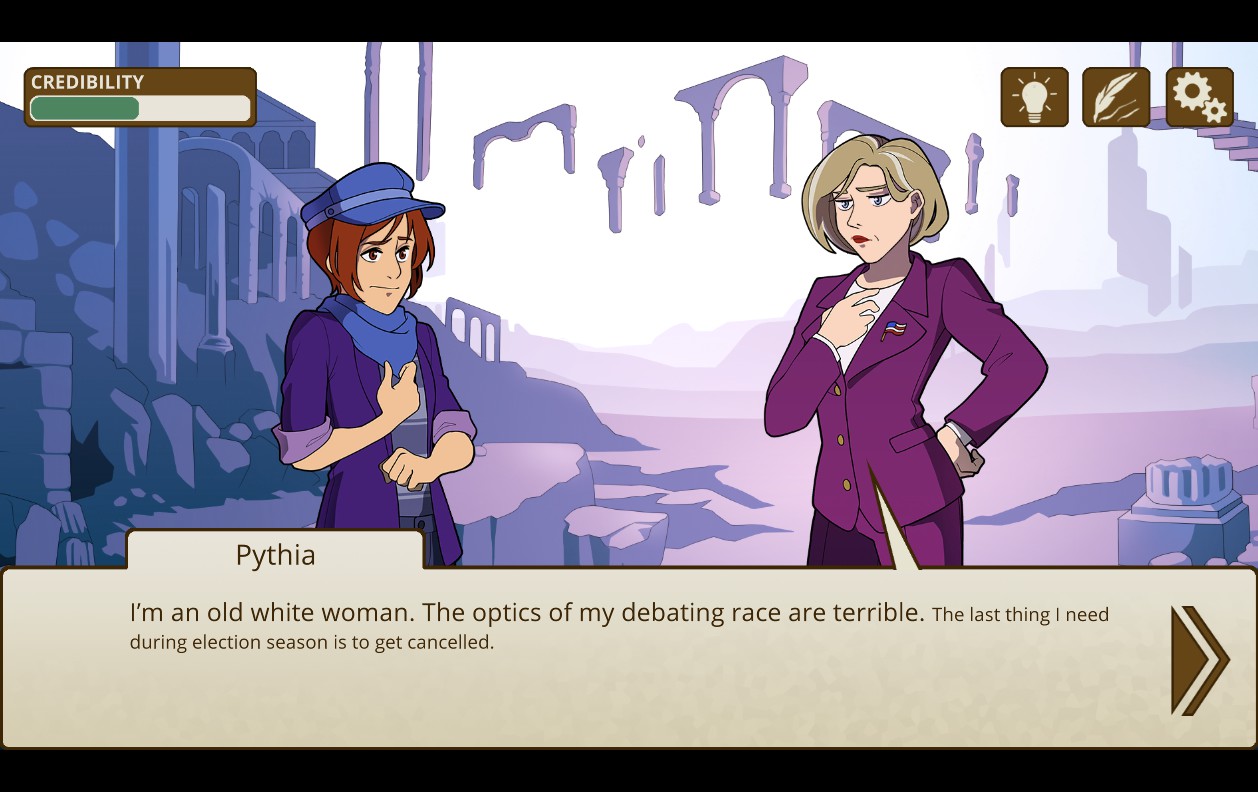

Clearly Locke’s Liberal democracy ain’t all it, but the dysfunction apparent in even Fanon’s revolutionary state and Nozick’s libertarian utopias makes her want to give up entirely. And that’s a sentiment I imagine you, reader, are familiar with. Though Americans would blush at having so many options as Ari (you can choose between Locke or Rawls!), it doesn’t take much time reading U.S. history to feel like representative democracy has never been good enough.

What breaks Pythia out of her spiral is the recognition that there is more good to draw on than just electoral politics in these ideas, and that philosophy can—is—still being written by the living for this moment.

The “final boss” of PP2 is Plato’s Republic—a government of Philosopher Kings. We know, having bested half a dozen of them, that they’re not the infallible paragons of Plato’s original vision. And to win that debate, you must challenge its assumptions not with radical new ideas, but with the contradictions and shortcomings you’ve found in each other philosophy you’ve already debated: alienation, self interest, oligarchy, etc.

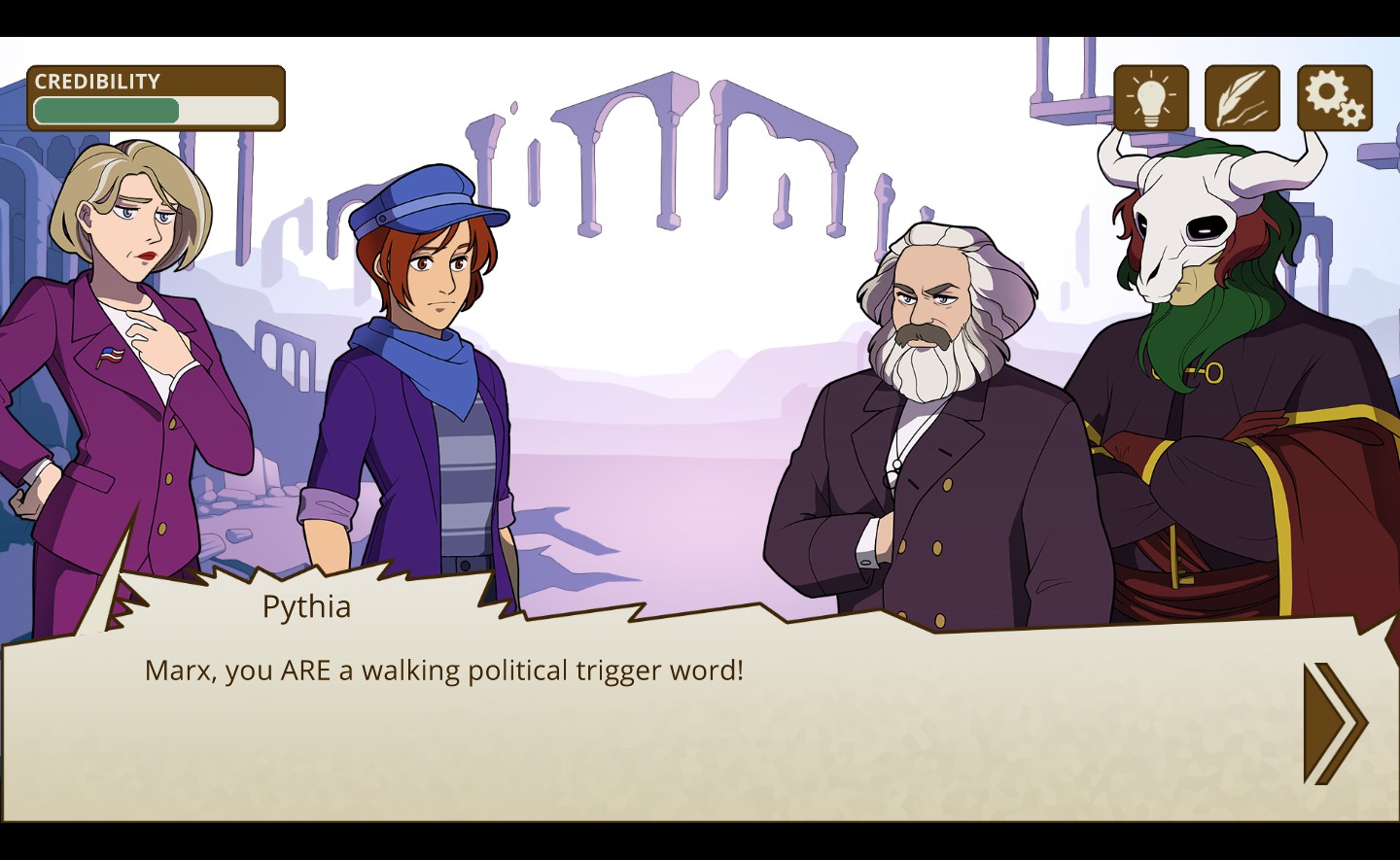

To say the absolute least, U.S. politics and philosophy have changed a lot in the 11 years since Intelligible Realms released its first debate sim. Political discourse is more reactionary. Party lines hold while policy shifts right. Alienation and burnout have driven many to anti-capitalist and anti-colonial philosophies, while masculinity-in-crisis has appropriated stoicism (presumably because it comes from ancient Rome).

PP2 has been in development in some form for much of the past decade. The world outside has changed, but the writings have not. Instead, they take on new meaning—like liberal, libertarian, Marxist, democrat, or republican all have. If even an anime Robert Nozick can yield, then I too can recognize contradictions in my own worldview.

But unlike in PP2, I can write my own argument for something better. The only explicit position the game ever takes is that an education in philosophy is a good thing (whether ethical or utilitarian). And that is a lesson worth taking outside of the game and into libraries that are funded by local electeds. As Ari and Pythia learn on their journey from the undead, with history and philosophy behind us, we don’t have to be tied down to what any ruling class is selling us this November.