Microbird talk about shaping Hinterberg's Austrian town through characters who both love and hate its sudden magical draw.

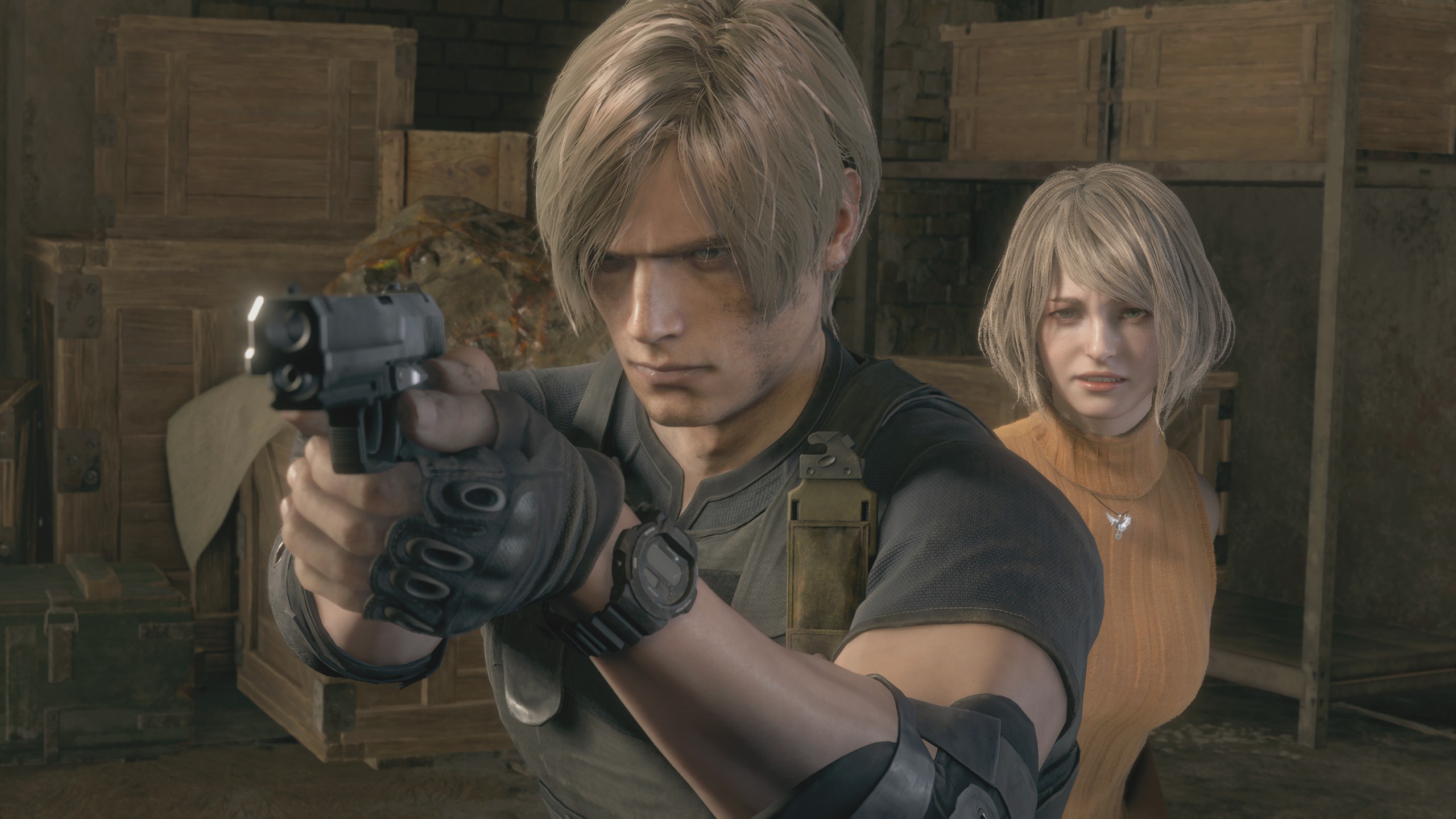

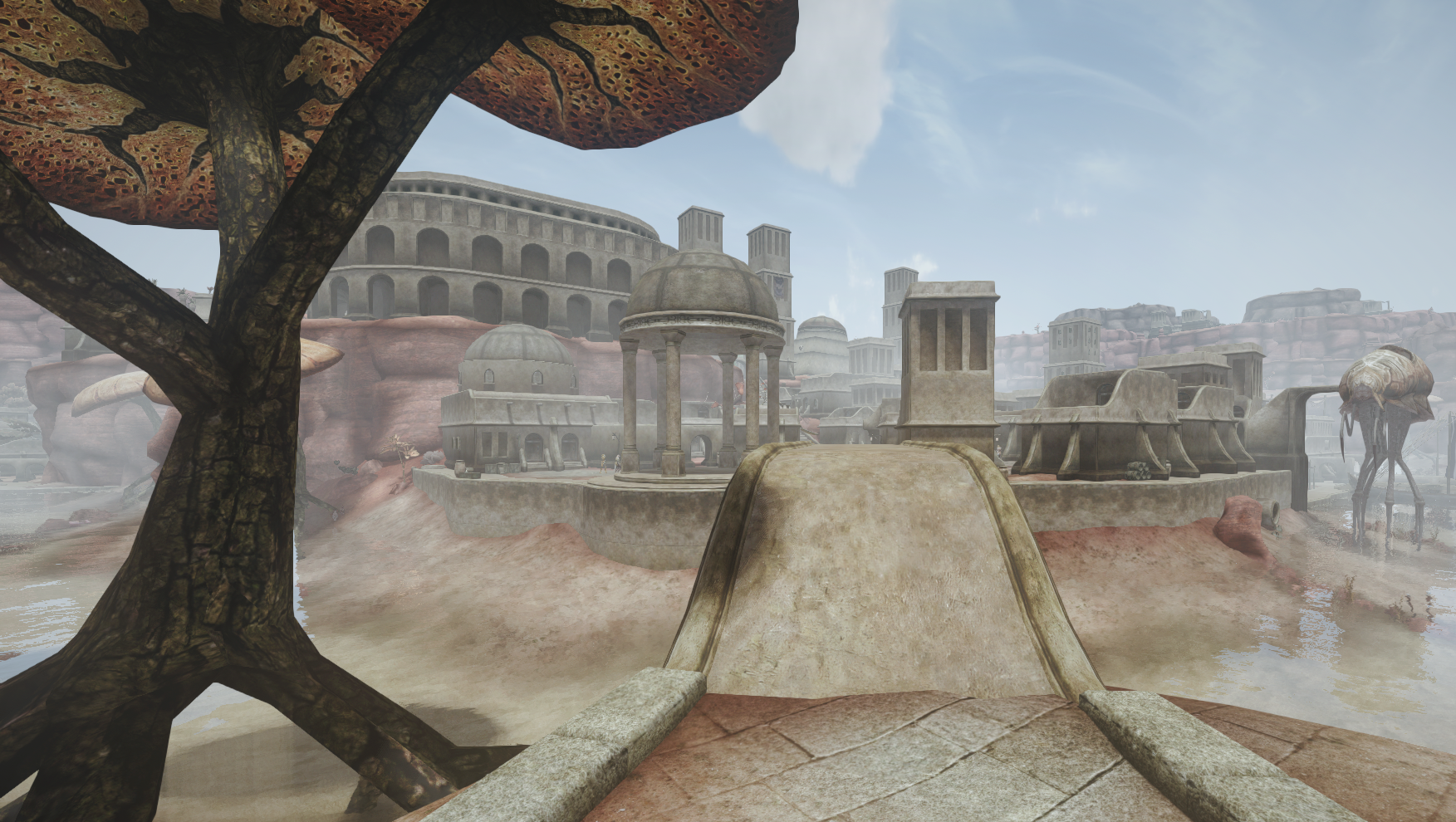

Since Dungeons of Hinterberg is a game about a vacation, it’s fittingly also a game about tourism. People flock to the imaginary Austrian village not to ski or sightsee but to explore dungeons, fight monsters, and use magic, which appeared seemingly randomly in Hinterberg a few years before the beginning of the game. Protagonist Luisa comes to Hinterberg to destress and have some fun, but by the end of the game she is knee-deep in questions about the impact the commercialization of magic has had on the city.

“It was for sure an angle that we wanted to explore, right from the start,” said Phillipp Seifried, cofounder of Microbird, in an interview with PC Gamer. “There’s this huge debate about tourism going on in places like Barcelona, which gets millions of tourists a year.”

“Three years ago magic appeared, and before that, it was a sleepy tourist place,” said cofounder Regina Reisinger. “Some people came for hiking or skiing, but it wasn’t a grade-A destination, it was just a mundane, normal place before something weird like magic happened. This balance and tension was what really interests us.” The effects the appearance of magic has on the city provide much of the central focus of the game.

When talking about inspirations for Hinterberg, Regina and Phillipp both spoke of the Austrian city of Hallstatt, a famously picturesque village with a population of 700 that sometimes hosts up to 10,000 tourists per day.

“You get a lot of debate about what to do with this, because on one hand, it’s beautiful that people from all over the world want to come and see your culture,” says Phillipp. “But at the same time it has an effect on the place that you’re visiting. […] There are people that profit immensely off of that. If you own a restaurant, you’re set for life, but if you’re a school teacher your life is not necessarily going to improve if there’s thousands of tourists to walk past every day.” This tension plays out directly in Dungeons of Hinterberg, as both locals and visitors take stock of magic and its impact in the face of the mayor’s increasingly determined commercialization of the village. The game, however, stops short of entirely taking a side.

“We didn’t want to make a political statement,” Phillipp said. “We wanted to show a real place.”

Regina added that the developers “don’t want the game to make a pro or con statement. We want it to explore all these layers. And this is the perfect sandbox to have all these different characters where some like it and some don’t, and you can let those characters speak to all the sides of the issue.”

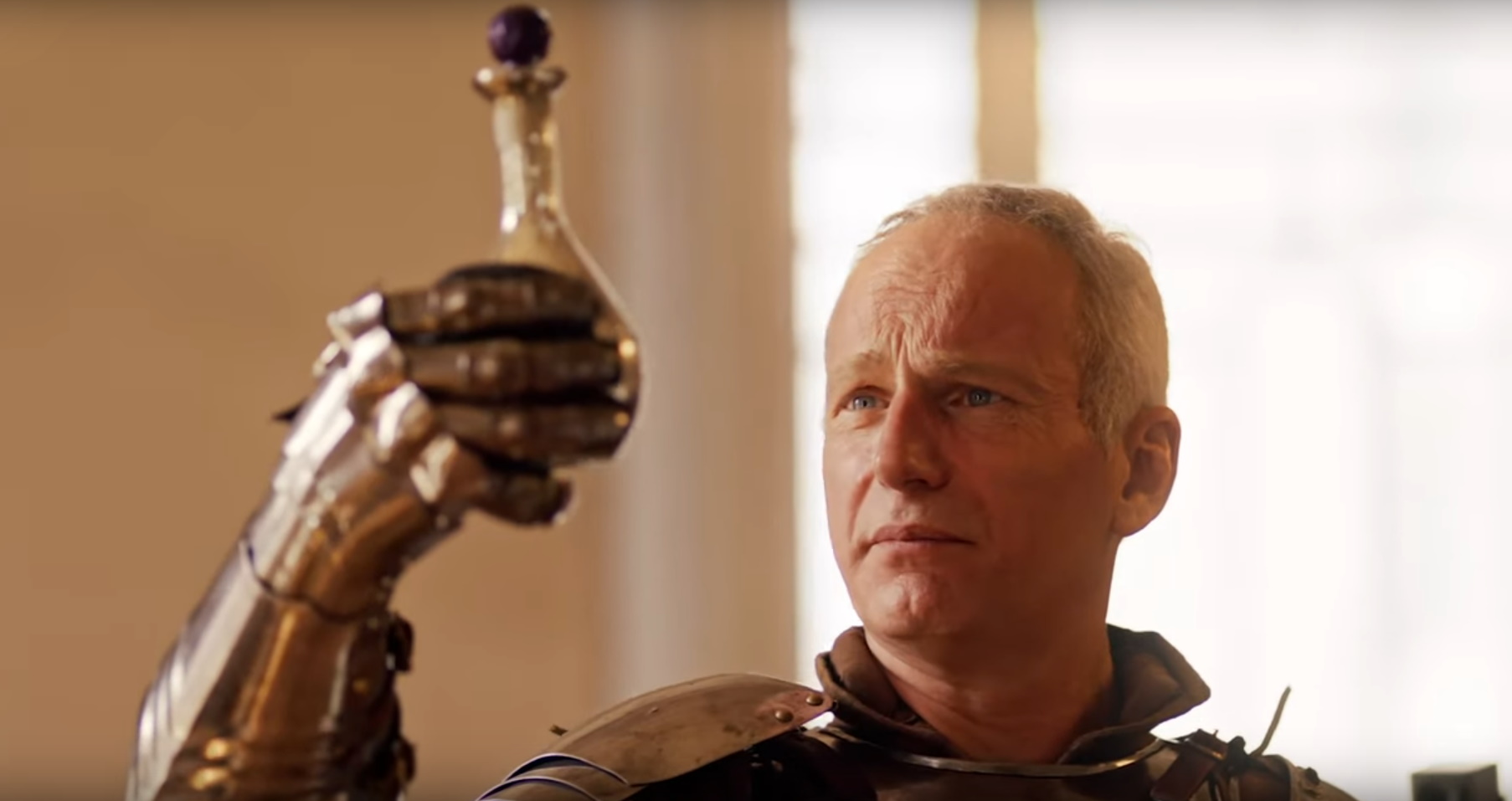

The diverse ways that characters in Hinterberg approach this issue is one of the strongest parts of the game. Of course there’s the mayor, whose drive to market the city internationally and compete with other magical hubs forms much of the story of the game. Though she’s in many ways comically greedy, almost a caricature, there are moments in the game where even she comes dangerously close to having a point. The tourism industry in Hinterberg has already begun, she argues in one scene; without the dungeons, that industry would disappear overnight, and with it the jobs and the economy around it. It’s a sleazebag politician’s argument, but it’s not untrue.

Other characters weigh in as well. Luisa’s first friend in Hinterberg, Alex, defends the dungeon industry when Luisa criticizes it, arguing that people from around the world getting to experience magic and share something special is a good thing. Klaus, a famous mountaineer turned dungeon trainer, struggles with how his job has degraded as the village has gotten busier, with higher traffic making dungeons less safe and visitors less respectful.

Collecting litter that is left in the wilderness and the dungeons and selling it back to him is a great, though sad, way to make money.

Thea, a local teenager, peers through her veil of careless adolescence to sarcastically criticize how little the money-obsessed government cares about the regular lives of Hinterberg’s citizens, and Gertrude, a rich widow who began visiting Hinterberg long before the arrival of magic, mourns the sleepy mountain town she first fell in love with. And then of course there’s Luisa herself, who came to Hinterberg to relax and finds herself caught between her own desires as a tourist and the impact she sees the dungeons having on the city.

Despite the magic and the dungeons and the monster-slaying, this commentary is effective because it’s sturdily rooted in reality. “People have asked us before if we think in reality, if magic and dungeons showed up, would it happen in the same way?” said Regina. “Because yeah, some of the game feels absurd, but we thought about it, and we do actually think it would kind of happen like that. It’s just in the nature of humans to be like, oh, a shiny new thing, we can do stuff with it! And then we rush ahead, and maybe five years later you start thinking of regulations.

“Some of it was easy for us to write because this is the country we grew up in, and we can pick inspiration easily, but the commercialization and this kind of politician that just takes these opportunities—that’s very universal.”

You can read more about how Dungeons of Hinterberg balances a captivating puzzle adventure with the social elements of the town in my review. The developers also spoke to us about why it’s not quite your typical cozy game.