And calls Project Soul "an elite group, a sophisticated development team."

Soulcalibur 6 released in 2018 to a decent reception, though it’s fair to say it didn’t set the world alight. The best thing about it was a ludicrously impressive character creator, though on PC even further treats would await thanks to modders: how about a fight to the finish between Bernie Sanders and Geralt?

Things have gone quiet on the Soulcalibur front since then, while stablemate Tekken’s star has continued to rise. Bandai Namco has developed these two very different flavours of fighting game simultaneously since the late 1990s, but with no new entry seemingly even planned some fans are beginning to worry that the success of Tekken will see Soulcalibur fade away.

“Where are those arcade titles that we were so crazy about? Where did that fighting game franchise with those great mechanics go?”

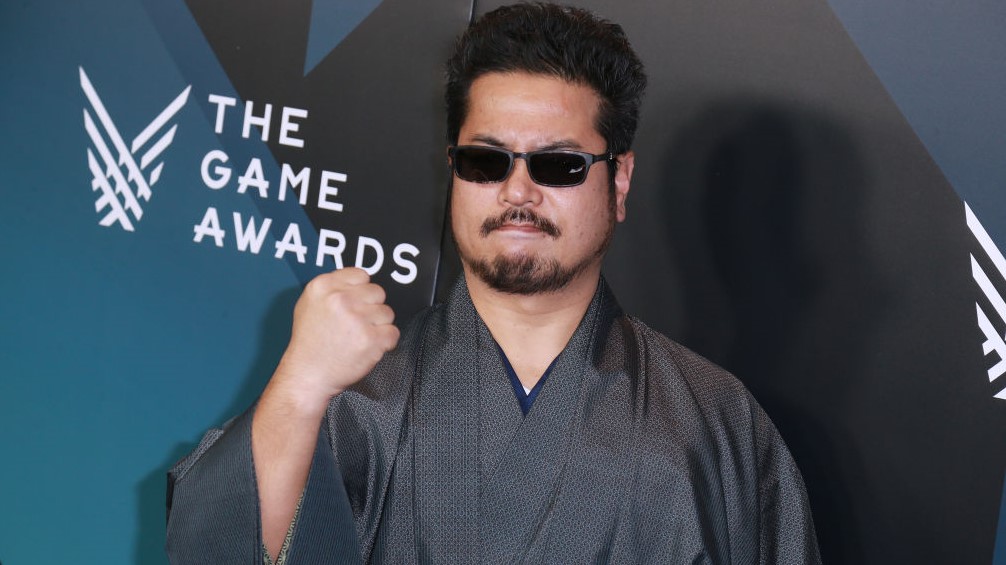

Katsuhiro Harada

A series fan posted a long thread outlining the reasons they felt Soulcalibur was in the doldrums, including the claim that it lacked a strong focal point like Tekken chief Katsuhiro Harada, and some spitballing about various game mechanics. Just another day on the gaming internet, but this sparked a remarkably long response from Katsuhiro Harada himself, who clearly had something to get off his chest.

Harada’s missive is detailed and somewhat brutal about what goes on behind-the-scenes at a giant publisher like Bandai Namco, and what it takes to keep pushing forward a massive brand like Soulcalibur or Tekken.

Harada begins by addressing the idea that various game mechanics affect a series’ survival or otherwise: “things are not that simple.” He points out that these games began in the heyday of arcades (the first Soulcalibur, Soul Edge, was an arcade cabinet before home conversions followed) where people could experiment more with games, and move between favourites, but in the home market your players have already purchased the game.

He calls this a “paradigm shift” in how games are marketed and sold, and for “historical video game franchises” this can be a big problem.

“It is too naïve and innocent a point of view to leave everything to game mechanics when talking about the survival of a game franchise,” writes Harada. “If they are so innocent, why did that game title that was so fun to play disappear?

“Where are those arcade titles that we were so crazy about? Where did that fighting game franchise with those great mechanics go? Why did that fighting game with those good mechanics disappear?”

Harada says there are many beloved titles that have disappeared, and points out how many different fighting game series there were in the late ’90s compared to now, joking that “there must have been some titles you rated as having much better mechanics than Tekken!”

(Image credit: Bandai Namco)

Boss mode

Then Harada gets to the point that really seems to have roused him: the idea that if Soulcalibur had long-term leadership like Tekken it would still be vital. With Soulcalibur, says Harada, it “was not simply a matter of sales and marketing, but I can tell you that the organizational changes and decision makers at Namco Bandai had a great deal to do with it.”

Harada has worked on Soulcalibur titles in the past, and was co-director on Soulcalibur IV, but says he’s always maintained “a certain distance” from Bandai Namco’s other big fighting game.

“In the past, the SC series had a strong leader named [Hiroaki] Yotoriyama (who was also once the animation team leader of Tekken), and above all, the team of engineers was more knowledgeable about fighting games than Tekken, and had excellent programming skills,” says Harada, who goes on to call Project Soul “an elite group, a sophisticated development team.”

Internally, the rivalry between the two series “was intensifying,” recalls Harada. “I was in the same game designer department as Yotoriyama of Project Soul, but we had friction to the point where we fought daily.” Harada says after this period “we were very close” but then after that Yotoriyama “quit Bandai Namco”, and the rivalry between the two brands remained high.

“The two projects had different visions, different development policies, and very different ways of thinking about the brand,” says Harada. They didn’t hate each other, but “they were such rivals that it was not surprising to think so.”

Or as the other side put it, per Harada: “Yotoriyama always said, ‘There is no point in putting the needs of Tekken into Soulcalibur,’ and I agreed with him.”

Harada goes on to say that “Project Soul certainly had a leader and staff with ‘soul’ and ‘clear vision’… The enthusiasm of the game designers on site could have surpassed that of the Tekken team, and it was enough to make us feel impatient. If Project Soul had been able to maintain that structure, I sometimes wonder if things might be a little different today.”

Soulcalibur apparently outperformed Tekken on consoles in North America, whereas Tekken did very well in arcades and sold well across all regions. “SC was always seen as having a promising future, even within Namco, and was considered to be capable of expanding beyond the realm of fighting games in a rather global perspective,” says Harada.

(Image credit: Bandai Namco)

Soul survivor

“We were never obedient, but always a wicked group with a strong will.”

Katsuhiro Harada

But things changed as the games industry expanded and Namco itself became a much bigger company through its merger with Bandai. Harada says few of today’s executives have backgrounds in game design, while most designers are spread across multiple disciplines in service of career progression rather than mastering their field.

“Each time a project’s key players were peeled away, the big dreams and visions that the project once held became weaker,” says Harada. “Project Soul was struggling to survive (or so it seemed to me), especially among its younger members.” The same thing happened to him as he became head of a global business development unit at Bandai Namco. That could’ve been the end of his involvement in Tekken… but Harada had other plans.

“I made the decision to lead the Tekken Project despite the fact that I was in a different company, department, and division, and had no budget authority,” says Harada. “I practically manipulated the creative and budget planning.”

Harada felt that Tekken’s survival depended on the team being willing to swim against the diktats from above. “A head appointed solely for career advancement, with no love for that game title and no long term vision, cannot be good for the survival of the series or the fan community,” says Harada.

“We, Tekken Project, always said that ‘the rights to the title belong to the company, but the fan community can only rely on the team that has the will to make the game’.

“I decided to continue to play the role of “Tekken Project leader,” which was not directly related to my original duties, and proceeded with the development as an independent team,” says Harada. “This move was very much disliked by the publisher, and the department head must have been very uncomfortable with it. Yeah, he hated me so much.”

Thanks to this Tekken Project survived as “a group of outlaws” and are able to make independent decisions within Bandai Namco.

“If there is only one major difference between Project Soul and the other groups, this is the only one”, says Harada. “In Tekken, Heihachi and Kazuya say ‘A fight is about who’s left standing. Nothing else.’ This line used to be my motto. I kept this in mind throughout our rivalry with Soulcalibur, and even when the market for 3D fighting games was becoming increasingly competitive, I continued to tell my team, ‘No matter how you do it, the last one standing wins’. And this motto remained unchanged even in the midst of the major trends that occurred within the group companies.

“So we were never obedient, but always a wicked group with a strong will. I’ve realized through these experiences that, unfortunately, I probably have a bad personality. I think this was the only difference between Tekken Project and Project Soul. I think that the fact that the number of members who had the drive to keep the title alive, even if they had to jump through all kinds of pressure, decreased as the organization changed, and that is one of the aspects that weakened Project Soul little by little. I am not saying that is all. But it was a big factor. Happened due to organizational policy, not individual problems.”

Lest that seem too downbeat a note to end on, Harada offers a little hope.

“From my point of view, I don’t think the fire of Project Soul has been extinguished. There are still a few people in the company who have the will to do it. I would like to believe that they are just not united now.”

This is one of the most in-depth answers I’ve ever seen a developer give on social media, and the original post clearly hit some sort of a chord with Harada. I’m more of a Street Fighter man but I love following Harada’s antics around the latest Tekken (“hello cracker“), and his style of engaging with the community is both very funny and occasionally belligerent. If nothing else this shows that the aggressive personality is not an act, and that Harada has had to fight to stay a part of his beloved Tekken over the years. It may well have been what’s kept the series so vibrant.

The fact that Project Soul may have been whittled away little-by-little under those same pressures… well, that’s just sad.