SGF's fascination with small staff sizes discredits the integral work of external contractors and contributors.

While opening last night’s Summer Game Fest showcase, host and Game Awards founder Geoff Keighley noted how 2025 has been marked by the surprise successes of smaller game projects. Alongside “indie creations” that “stand side by side with heavyweights,” Keighley shouted out Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 from Sandfall Interactive, which he called “a monumental achievement” made by “a team of under 30 developers.”

Given Clair Obscur’s critical reception and its millions of sales, it’s compelling to think that fewer than three dozen people could produce such a success. That “under 30 developers” figure has circulated in conversation and coverage—it’s a claim we quoted from the game’s creative director in our own pre-release reporting. It’s an inspiring idea.

It’s also factually incorrect.

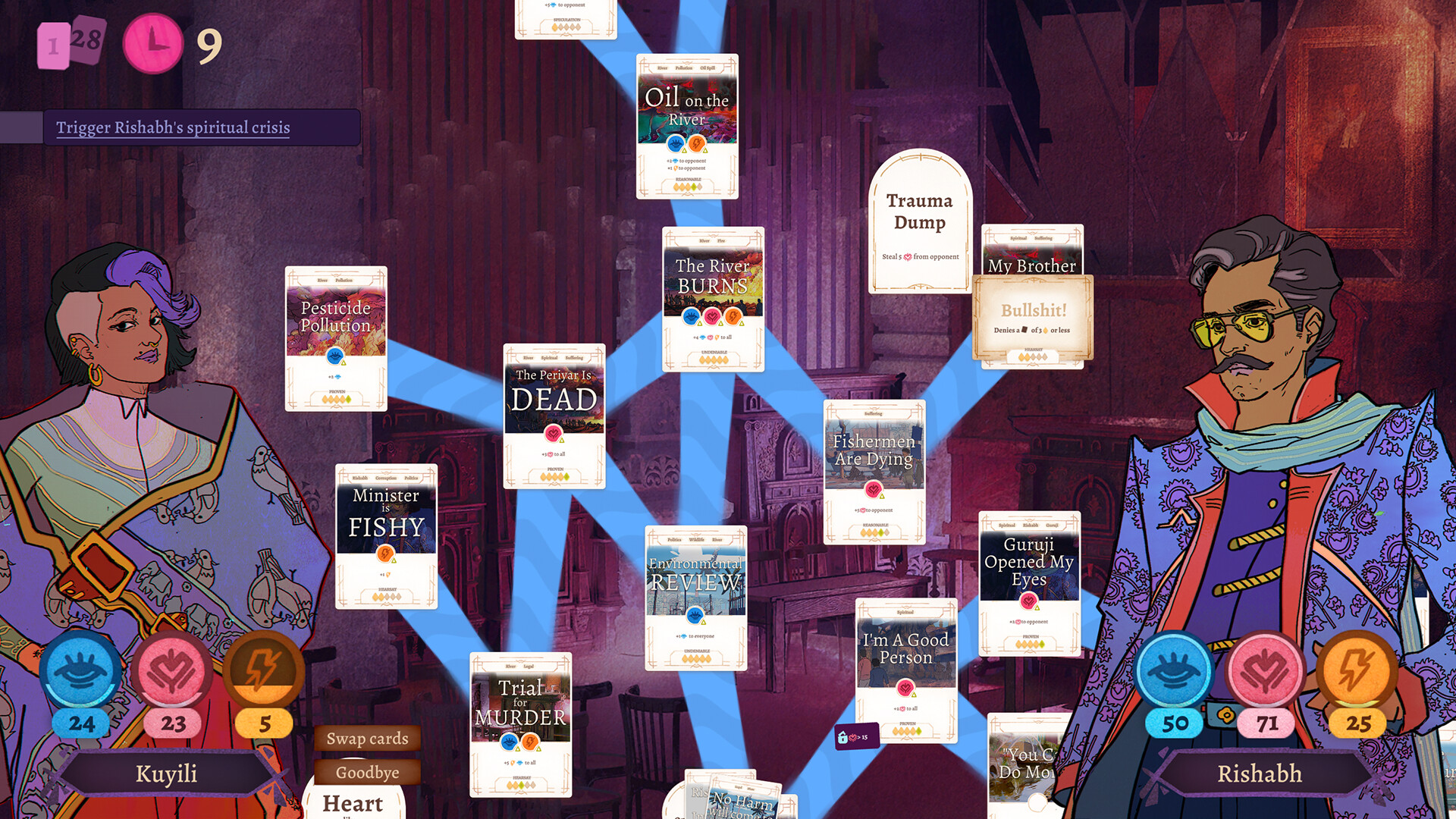

If you seek out a video of Clair Obscur’s credits (via Rock Paper Shotgun), you’ll find that—to its credit—Sandfall’s core development team does indeed number around 30 people, a small studio by industry standards. But the in-house Sandfall staff compose less than half of the game’s credits runtime, the rest of which is devoted to “production partners”—the kinds of external contractors and contributors that today’s games industry relies upon.

Clair Obscur’s credits include dozens of contributors: a team of Korean gameplay animators, QA staff from Polish firm QLOC, porting support from Ebb Software, performance and compatibility analysts from Huwiz QA/UX, audio producers and vocal performers from Side UK and Studio Anatole, localization staff from Riotloc, voice actors, performance capture artists and specialists, musicians, choir singers, retail distributors, interns, playtesters, mock reviewers, and more—all of whom were responsible, in part, for Clair Obscur’s quality, character, and global success.

Acknowledging those contributions detracts nothing from Clair Obscur’s achievement. It is, by an overwhelming majority of accounts, a good-ass videogame, and Sandfall’s core team should be celebrated for that. But misrepresenting the scale of its production, intentionally or otherwise, draws an implicit distinction between what does and doesn’t qualify as “real” game development.

If you’re justifiably annoyed when a game launches as a buggy mess, you should want the contributions of QA testers, who do the complex work of identifying those bugs before release, to be properly credited and valued. Otherwise, that integral labor—in QA, in localization, in compatibility testing—is seen as disposable, a perception that contributes to abusive working conditions in overseas contractor studios and drives recent unionization efforts in the US.

Game developers on Bluesky have reacted with frustration and discomfort to SGF 2025’s preoccupation with mythologically small dev teams. “It’s incredibly noticeable how often ‘and an army of outsources outside America and Western Europe’ is left out of these team sizes,’ said game director and Bithell Games founder Mike Bithell. “That’s the part I find real uncomfortable.”

Balatro creator Localthunk noted how he, too, is often credited as the “one guy” who made Balatro, which he says contributes to a “David vs. Goliath narrative” that’s been oversimplified. TVGS, the developer of Schedule 1, was also shouted out as “a solo developer” by Keighley during last night’s SGF. Schedule 1’s in-game credits show that art and music were provided by two other contributors.

“No it was not ‘one guy’,” Localthunk said. “Look at the dang in-game credits.”

“I was really uncomfortable with this as well. And not just because the math doesn’t math. One dev plus nine friends working with him is 10 people… not one,” said games licensing producer and consultant Mike Futter, referencing a moment at SGF when Keighley described upcoming brawler Acts of Blood as made by “a solo developer in Bandung, Indonesia with the help of nine of his friends.”

“Expedition 33 is a triumph, but it wasn’t made by 30 people. Contractors provided vital labor. This is a dangerous path we’re walking,” Futter said.

It’s not hard to imagine ways in which repeating the myth of Clair Obscur’s team size could contribute to worse conditions for games and the people developing them. If publishers and investors are convinced that games like Expedition 33 were made with only 30 developers, they’ll be less inclined to support the necessary staff and production budgets that development projects require—regardless of whether it’s true.