Toss a coin to your Witcher so he can pay for a better haircut.

To celebrate its 10th anniversary, all this week we’re looking back on The Witcher 3—and looking ahead to its upcoming sequel, too. Keep checking back for more features and retrospectives, as well as in-depth interviews with the developers who brought the game to life.

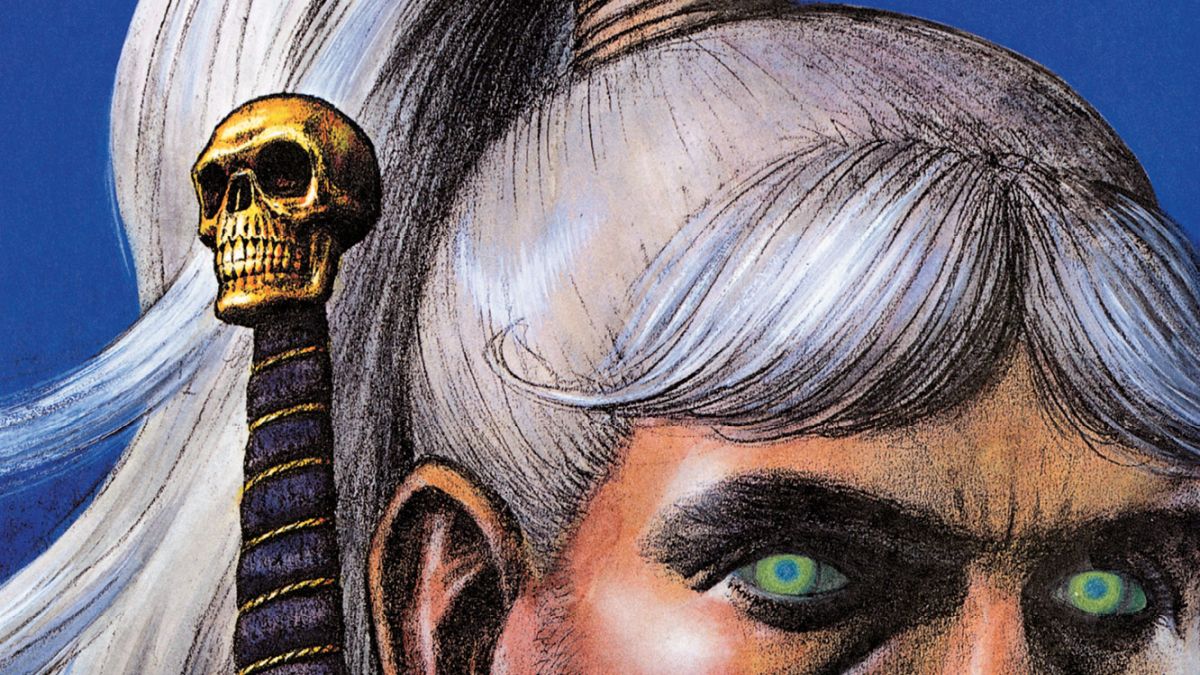

Let’s get this out of the way right up top. Yes, Geralt has bangs that look like they belong under the lip of an anime mad scientist. I don’t know if we can blame this on Poland or the 1990s or just fantasy comic books in general, but it does make for a rough first impression.

In 1993, seven years after Andrzej Sapkowski’s first Witcher story was published, writer Maciej Parowski and artist Bogusław Polch began adapting Geralt’s adventures into comics. Long before the videogames and TV shows, this was the first attempt at adapting The Witcher for a visual medium, so it’s not surprising that it’s idiosyncratic. It was Polch who turned Sapkowski’s red-eyed vrans into lizard-people, a depiction the videogames followed. Some of his other ideas weren’t so influential. Geralt’s fringe for starters.

Polch also has a thing for eyelashes, with his elves in particular having overgrown proliferations of them, like spiderlegs emerging from behind their eyeballs. Other likenesses are spot on, however, and his Yennefer is immediately recognizable. And even at its goofiest the art’s kind of charming, in a Métal Hurlant Eurocomic kind of way. Geralt punching a rider off a horse as he somersaults into the saddle is communicated with a pleasing economy, and when sorceresses work magic their hair stands on end and they end up looking uncannily like ’70s David Bowie.

Among these six chapters are adaptations of four short stories—The Witcher, The Lesser Evil, The Last Wish, and The Bounds of Reason—as well as two more unusual offerings. The first is an expanded version of a short story Sapkowski wrote about Geralt’s parents, originally part of a separate fantasy novel he was working on repurposed to provide more material for the suddenly in-demand Geralt of Rivia. The second is a new story based on an outline provided by Sapkowski in which young Geralt undergoes his Witcher trials as the School of the Wolf prepares to face off against its rival School of the Cat in a tournament.

Though this story was published last, in this collection the stories are ordered chronologically so it comes second, meaning there’s a fair chunk of prequel to get out of the way before the Geralt we’re here to read about takes centre stage. There’s a lot of added interconnectedness in the stories too, a very comic book thing to do—in this version of events Mousesack’s mother was killed by Geralt’s father, Yarpen the dwarf was one of Renfri’s original band of companions, and a young Dandelion shouted insults at a young Geralt in passing for no particular reason. I’m not sure filling them with crossover cameos adds much to the stories, but you can tell the writer’s having fun fitting the puzzle pieces together.

The later chapters are the more famous monster-hunting fairytale-parodying stories, which have been told multiple times now, in The Hexer and Netflix’s Witcher series and the more recent Dark Horse comics. While those versions seem like they’re in conversation with each other—the Dark Horse versions feeling like they’re only evoking the original stories to give Netflix haters something to latch onto, rather than out of any actual desire to do something interesting with them—these early interpretations are figuring things out as they go.

It’s a version of The Witcher where wizards wear stereotypical conical hats even when they’re drunk and acting up, one that’s closer to the aesthetics of trad fantasy, which emphasizes the grim-and-gritty elements even further. It makes some bold and colorful choices a modern adaptation wouldn’t, and while sometimes that results in a laughable haircut, sometimes the result’s a refreshingly skewed take on Sapkowski’s original stories.