Vvardenfalling in love again.

It’s strange experiencing a sense of urgency in a game I’ve played for hundreds of hours. But that’s what happens when I begin a new adventure in Morrowind: a Pavlovian response that makes me want to charge out of the character creation section and start exploring, even though I know I’ve seen it all before.

This article first appeared in PC Gamer magazine issue 408 in March 2025, as part of our ‘Reinstall’ series. Every month we load up a beloved classic—and find out whether it holds up to our modern gaming sensibilities.

Before I can even get to that, however, are the waves of nostalgia. Hearing the creak of timber ships and the reassuring calm of Azura’s voice rockets me back to 2002, and the overwhelming promise of freedom, the likes of which, back then, I’d never experienced.

Watching the intro reminds me of the stories sparked from my previous experiences: vampire knights, noble savages, reluctant messiahs, hired killers. It’s abandoned shacks full of books, sunrises at the foot of statues.

I’m getting ahead—or perhaps behind—myself. I’m not even off the ship yet. The guard arrives and all I can think about is rushing past him so he doesn’t slow me down as I sprint to freedom: a manoeuvre I’ve repeated hundreds of times to speed up the intro. In the best possible way, the opening 30 minutes is pure muscle memory.

I make my character, steal everything I can from the first room so I can sell it, collect Fargoth’s ring, return it to him to improve my reputation with his friend, Arrille. Even this small act reminds me why the game is so special: I’m five minutes in and I have a contact in the first area, whose backstory I know, and a preferred vendor, from whom I’ll get better prices.

This specificity is what makes the game sing. On the one hand, Arrille is just another High Elf trader with the exact same face and voice as a hundred other NPCs; on the other, he’s the person who sold me my first sword, and a character who means more to me than most of the cast of Skyrim. I wonder if the people and places in Morrowind have the strange emotional resonance precisely because it’s a simpler game than its scions. There’s more room here for players to use their imaginations, carve their own stories. I’m filling in narrative gaps that aren’t present in Skyrim or Oblivion.

I roll a Redguard and choose a custom class, specialising in skills I know will help me survive Morrowind’s often frustrating opening hours. This choice is mainly to aid with combat: I want to begin with the highest possible Long Blade skill, so I don’t spend the next six hours swinging at Cliff Racers and missing. But it’s also a narrative leg up: I decide to make my hero, Mundas, a privateer, because it a) feels like a good match to my skill set and b) it sounds more civilised than pirate. Skilled of blade, sharp of tongue, swift of foot; Mundas is the consummate adventurer.

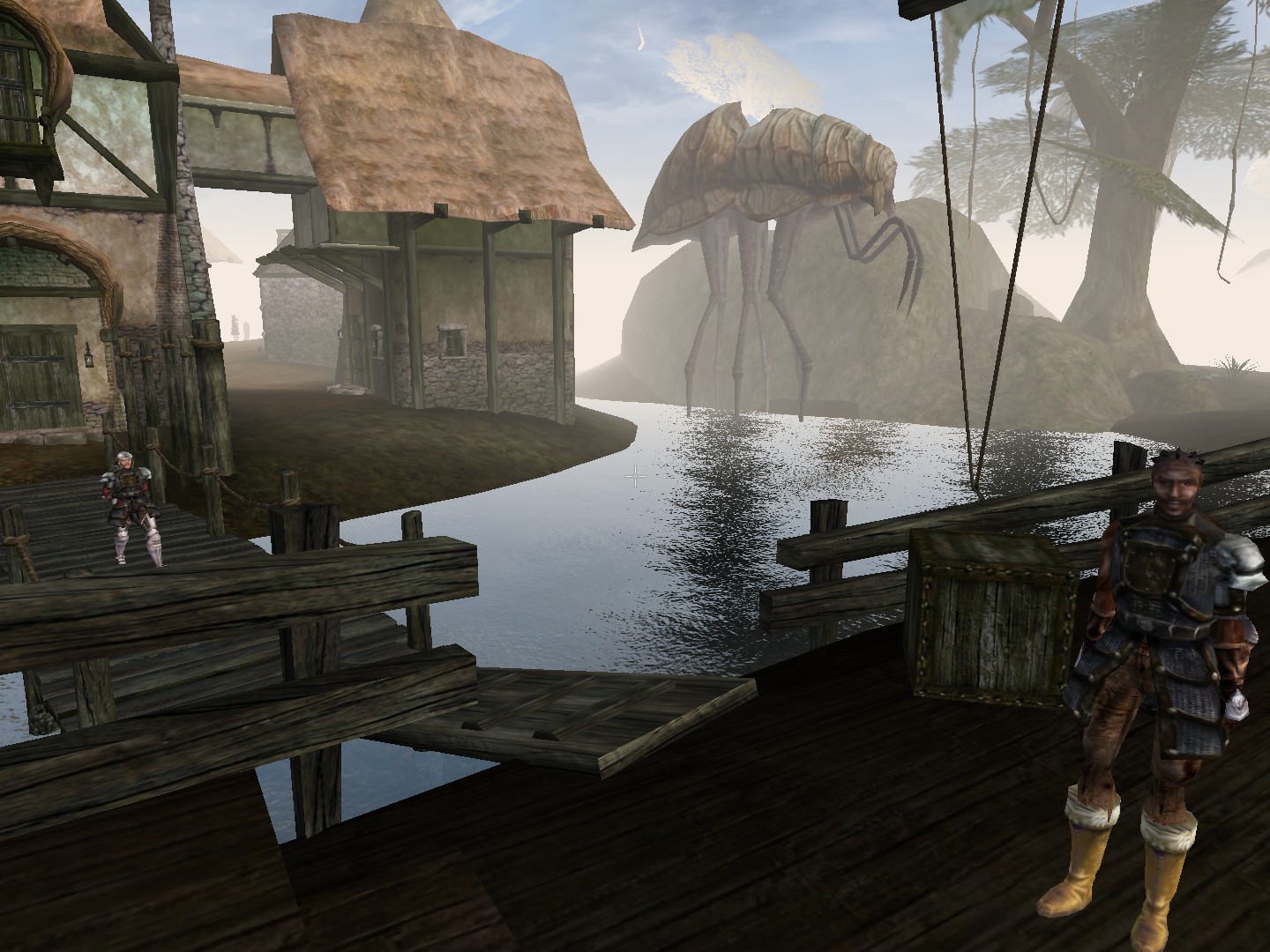

From here, it’s a mix of routine adventure and semi-religious experience. Getting off the boat and seeing the light reflecting off the water, Silt Strider shrouded in the distant mist, is like revisiting the locked storeroom in my mind palace.

I’d forgotten how much this world means to me. The stupidest moments suddenly feel transformative: murdering smugglers, fighting my first mudcrab, hearing Tarhiel wail as he falls to his ignominious death. It’s glorious to be back.

I could take public transport to my next destination, Balmora, but adventure dictates that I use the slower, more interesting path. I remember my first journey from Seeyda Neen to Balmora: how long it took, how often I got lost, how I had to use an actual, physical map for guidance. And, doing it again, I can see why. I stop off at Pelgiad and accidentally make special friends with a horny Khajit called Ahnassi after she compliments my smooth moves. For some players, their adventure would end there: engaged to a gregarious cat-lady before they’ve even completed the first quest. It’s like a trap.

Fetcher Quest

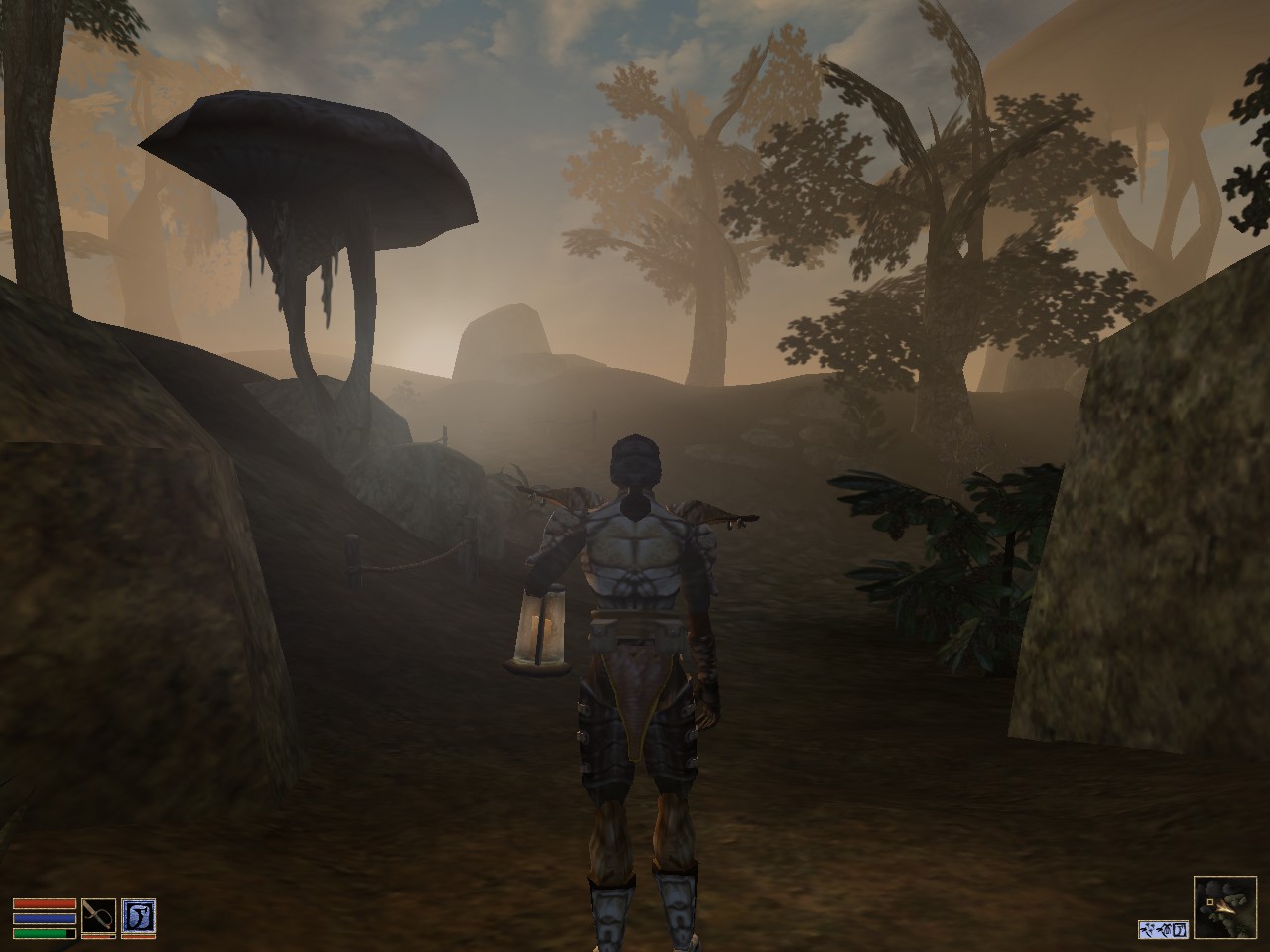

There’s so much else to see, even on this short journey. As well as all the distracting quests—including a damsel-in-distress who asks you to locate the robber she’s fallen in love with—the geography itself is strangely affecting. I love the horror and weirdness of Ghostgate, and the knowledge that the main quest will eventually take me there. I’m still captivated by the misty, liminal, mushroomy landscape.

Even public transport, infrastructure, and the economy feel alien, all based on the proliferation of giant insects in Vvardenfell. It’s such an unusual, specific take on high fantasy that it still feels fresh. The dragons and trolls and forests of Oblivion and Skyrim, by comparison, feel numbingly generic.

By the time I finally reach Balmora, I’ve seen enough distractions to make me feel like I’ve already been on adventure. And I’m met with conflicting feelings. On the one hand, I’m glad to be out of howling winds and into a place of comfort. The ash storms and howling winds of Morrowind make getting inside even more appealing. But another part of me wants to keep walking north, to the strange, crab-shell buildings of Ald’Ruhn, past the West Gash, all the way to Khuul and the northern shores of the island. For some reason, for me, the geographical changes here are more tangible and compelling than in anything that followed. I might be imagining it, but certain areas feel like they have more danger, too; the further from the starting area I stray, the more often I find myself fleeing from flocks of blighted cliff racers or roaming daedra.

I stick around Balmora, mainly so I can reacquaint myself with the locals. I drop off a package to Caius Cosades, a member of the Emperor’s spy network who’s gone so deep undercover that he’s accidentally become a genuine drug addict. He’s one of Bethesda’s best written characters: a fatherly tangle of honesty and ambiguity, who guides you through the main quest and supports you when you declare yourself the reincarnation of an ancient Dunmer god; a level of support I aspire to provide as a dad and/or manager.

This is one of the elements that benefits from the reams of text. There’s more depth and subtlety. I find myself trusting people who Caius trusts, and it guides my choices. And even the early missions introduce you to the depth and ambiguity of the game. Yes, I’m killing rats and dealing with egg poachers, but I’m also dealing with Eydis Fire-eye, a Fighters Guild member who assigns quests early in the game. And while some of them seem normal—see the rats above—it quickly becomes apparent that not all is as it seems.

The cool thing here is that the onus is on me, as the player, to dig deeper. By asking trusted contacts, such as Caius, I can end up uncovering the rot within the heart of the Fighter’s Guild. Or I can just do as I’m told. It’s magnificent.

Nerevar-ending Story

To finish with, I decide to explore a Dwemer ruin at the request of one of Caius’s contacts. He wants a mysterious puzzle box, which absolutely feels like the sort of cursed artefact that I don’t even want to be in the same room as, let alone hold. And even finding the ruin is a challenge, because Morrowind doesn’t have map markers. Instead, I have to follow vague instructions in my journal, like a waddling tourist asking for directions to the Arc de Triomphe in broken French.

When I finally arrive, I delve too deeply into the ruins, reaching a ghost-infested lava pit filled with monsters I can’t fight because I only have an iron saber. I heroically flee, and, on the way out, I accidentally discover a room that contains the puzzle box. This, then, encapsulates the joy and madness of Morrowind. The item isn’t on any map. It’s not in the possession of a notable NPC. It’s on the bottom shelf of a Dwemer MALM bookcase, in a room most people will walk right past. You engage with your surroundings in Morrowind, or you fail.

It’s insane. And I love it. I could play this game forever. There’s an enforced slowness that will make some players gnaw through their mouse mats, but, for me, it adds a sense of narrative richness that’s rarely been bettered since. It takes time to do everything. I can level up skills faster in real life than I can in-game. When you finally ascend through the ranks of the Fighter’s Guild, for instance, it feels like it has value.

Pace and ambiguity improve it, somehow. You’re not blindly waddling towards a map marker: you’re reading descriptions, analysing your surroundings, becoming familiar with the world. I know the towering fungi and volcanic holloways of Vvardenfell with the same clarity as the pastry counter at Greggs.

There’s nothing stopping me playing Skyrim like this—or modding it to be more like Morrowind—but it’s not just a case of avoiding fast travel. The design decisions are supported by a foundation of detail and wonder that’s less present in later games. It’s the difference between wearing armour that consists of four parts, compared to eight. I will never be as proud of the set in Skyrim as the one I had to fight hard to find in Morrowind.

I hope that the upcoming Elder Scrolls game has a similar level of complexity. I’m not expecting levitation, magic locks, spears, staffs, short blades and throwing weapons; just a world of complexity and mystery, where my boss is a drug addict and I can accidentally marry a cat.