Doom Is Having Its Halo Moment With The Dark Ages

The last thing I expected Doom: The Dark Ages to remind me of was Halo 3. And yet, half way through a recent hands-on demo with id Software’s gothic prequel, I was mounted on the back of a cyborg dragon and unleashing a salvo of machinegun fire across the side of a demonic battle barge. With the vessel’s defensive turrets destroyed, I landed my beast atop the ship and proceeded to charge through its lower decks, turning the entire crew into a few gallons of red slop. Seconds later, the warmachine was toast and I burst through its hull, leaping onto my dragon to continue my crusade against the machines of Hell.

Those familiar with Bungie’s landmark Xbox 360 shooter will instantly recognise the shape of Master Chief’s assault on the Covenant’s scarab tanks. The helicopter-like Hornet may have been swapped for a holographic-winged dragon and the giant laser-firing mech for an occult flying boat, but the core of the experience is all here: an aerial assault that transitions into a devastating boarding action. Surprisingly, this wasn’t the only moment in the demo that reminded me of Halo. While the combat core of The Dark Ages is unmistakably and singularly Doom, the campaign’s design seems to have a very “late-2000s shooter” spin thanks to its love of elaborate cutscenes and a greater push for gameplay novelty.

Across two and a half hours I played four levels of Doom: The Dark Ages. Only the first of them, the campaign’s opener, resembled the tightly paced, immaculately mapped design of Doom (2016) and its sequel. The others saw me piloting a colossal mech, flying the aforementioned dragon, and exploring a wide-open battlefield dotted with secrets and powerful minibosses. It’s a big departure from Doom’s usual pursuit of mechanical purity, instead feeling akin to the likes of Halo, Call of Duty, and – weirdly – old James Bond games like Nightfire, all of which thrive on scripted setpieces and novelty mechanics that guest star for a mission or two.

This is a fascinating direction for Doom to head in, because once upon a time the series made something of a U-turn away from this. The cancelled Doom 4 was set to resemble Call of Duty, not only due to its modern military aesthetic but also thanks to an increased emphasis on characters, cinematic storytelling, and scripted events. After years of work id Software concluded that such ideas simply weren’t a good fit for the series, scrapping them in favour of the much more focused Doom (2016). And yet, in 2025, here they are in The Dark Ages.

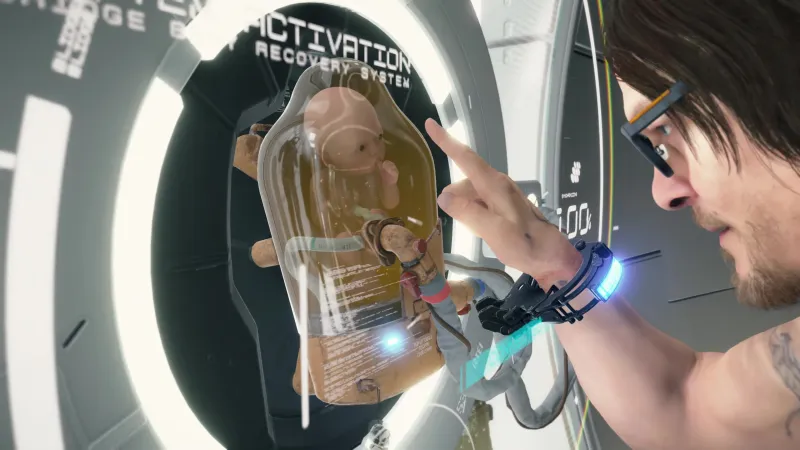

My demo opened on a long and elaborate cutscene, (re)introducing the realm of Argent D’Nur, the opulent Maykrs, and the Night Sentinels – the knightly brothers-in-arms of the Doom Slayer. The big guy himself is depicted as a terrifying legend; a nuclear-level threat on two legs. While all of this lore will be familiar to Doom obsessives who poured over the prior games’ codex entries, the deeply cinematic approach with which it’s now presented feels very new. Very different. Very Halo. That continues into the levels themselves, with NPC Night Sentinels scattered about the environment akin to UNSC Marines. While they don’t fight alongside you (at least not in the levels I demoed) there’s certainly a greater sense that you’re part of an army – like Master Chief, you’re the invincible spearhead of a large force.

There’s a lot of character work in the introductory cutscene and it remains to be seen if this is something Doom really needs. I’m a big fan of the prior games’ slight approach to story, and part of me would rather The Dark Ages continued to tell the Slayer’s tale through environment design and codex entries, reserving cinematics only for the big reveals à la Eternal. But while I have my reservations, the cutscenes thankfully know their place: they tee up a mission and are never seen again, refusing to interrupt Doom’s signature intense flow.

There are interruptions in other forms, though. After that opening mission, which starts with pure shotgun slaughter and ends with you parrying Hell Knights using the Slayer’s incredible new shield, I was thrown into the cockpit of a Pacific Rim-like Atlan mech and asked to wrestle demonic kaiju. After that, I was soaring through the skies on that cybernetic dragon, taking down battle barges and picking off gun emplacements. These tightly scripted levels create a significant gear shift, punctuating the campaign’s rapid pace with new gameplay ideas that are reminiscent of Call of Duty’s biggest novelties, such as Modern Warfare’s AC-130 gunship sequence or Infinite Warfare’s dogfighting missions. The Atlan is slow and heavy, and the skyscraper-high perspective makes Hell’s armies look like Warhammer miniatures. The dragon, meanwhile, is fast and agile, and the shift to a wide-angle third-person camera results in a very different experience that feels a dimension away from classic Doom.

Many of the best FPS campaigns thrive on this kind of variety. Half-Life 2 and Titanfall 2 are the gold standard for it. Halo has endured so long partly because its mix of vehicular and on-foot sequences provides it with a rich texture. But I’m unsure if this will work for Doom. As with Eternal, The Dark Ages is once again a wonderfully complex shooter to play – every second demands your complete attention as you weave together shots, shield tosses, parries, and brutal melee combos. In comparison, the mech and dragon sequences feel anemic, stripped back, and practically on-rails – their combat engagements so tightly controlled they almost resemble QTEs.

In Call of Duty the switch to driving a tank or firing from a circling gunship works because the mechanical complexity of such scripted sequences isn’t that far removed from the on-foot missions. But in The Dark Ages there’s a clear gulf between gameplay styles, so much so it’s akin to a middle school guitar student playing alongside Eddie Van Halen. And while I know Doom’s core combat will always be the star, when I’m beating the snot out of a giant demon with a rocket-powered mech punch I shouldn’t be wishing I was back on the ground using a “mere” double-barrelled shotgun.

My final hour of play saw The Dark Ages shift into another unusual guise, but one built on what feels like a much sturdier foundation. “Siege” is a level that returns its focus to id’s best-in-class gunplay, but it opens up Doom’s typically claustrophobic level design into a huge open battlefield, its geography shifting between narrow and wide to provide a myriad of pathways and combat arenas. The goal, to destroy five Gore Portals, has the same energy as Call of Duty’s multi-objective, complete-in-any-order missions, but I was reminded once more of Halo – the grand scale of this map versus the tighter routes of the opening level evokes the contrast between Halo’s interior and exterior environments. And, like Halo, the novelty here is that the excellent core shooter systems are given new context in much larger spaces. You must rethink the effective range of every single weapon in your arsenal. Your charge attack is employed to close football field-length distances. And the shield is used to deflect artillery fired from oversized tank cannons.

The downside of expanding Doom’s playspace is that things can become a little unfocused – I found myself backtracking and looping through empty pathways, which really does kill the pace. It’s here I’d like to have seen The Dark Ages veer even closer to Halo by throwing the dragon into the mix and using it like a Banshee; being able to fly across this battlefield, raining down fire before divebombing into a miniboss battle, would have helped maintain the pace and make the dragon feel more integral to the experience. If such a level exists beyond what I’ve seen, I’ll be very happy.

Regardless of the overall shape of the full campaign, though, I am fascinated that so much of what I’ve seen feels like a resurrection and reinterpretation of ideas that were once considered an ill-fit for the series. Very little of the cancelled Doom 4 was released for the public to see, but a Kotaku report from 2013 paints a distinct picture. “There were a lot of scripted set pieces,” a source told the publication, among them allegedly an “obligatory vehicle scene.” And that’s exactly what we’ve got in the Atlan and dragon sections – mechanically simple scripted sequences that hark back to the novelty vehicle levels of Xbox 360-era shooters.

Talking to Noclip in 2016, id Software’s Marty Stratton confirmed that Doom 4 “was much closer to something like [Call of Duty]. A lot more cinematic, a lot more story to it. A lot more characters around you that you are with throughout the course of the gameplay.” All that was scrapped, and so it’s genuinely fascinating to see so much of it return in The Dark Ages. This is a campaign set to feature big boarding action setpieces, lusciously rendered cinematics, a much wider cast of characters, and huge lore reveals.

The question now is: were those ideas always a bad idea for Doom, or were they just a bad idea when they looked too much like Call of Duty? Part of me is just as skeptical as the fans who once decried “Call of Doom”, but I’m also excited at the idea of id Software finally making that approach work by grafting it on to the now-proven modern Doom formula.

The beating, gory heart of The Dark Ages unquestionably remains its on-foot, gun-in-hand combat. Nothing in this demo suggested that it will not be centre stage, and everything I played affirms it’s another fantastic reinvention of Doom’s core. I think that alone is strong enough to support an entire campaign, but id Software obviously has other designs. I’m surprised that a couple of the studio’s new ideas feel so mechanically slim, and I am concerned that they will feel more like contaminants than fresh air. But there’s still a lot more to see, and only in time will these fractured demo missions be contextualised. And so I eagerly await May 15th, not just to return to id’s unrivaled gunplay, but to satisfy my curiosity. Is Doom: The Dark Ages a good late-2000s FPS campaign or a messy one?

Matt Purslow is IGN’s Senior Features Editor.