PC Gamer's original 2004 review of Half-Life 2.

20 years ago, Half-Life 2 was the recipient of two of PC Gamer’s highest review scores ever: 96% in PC Gamer UK, and 98% in the US version of the magazine, which at the time published separate reviews.

“This is the one unmissable game,” UK reviewer Jim Rossignol concluded. “It’s time to get that cutting-edge PC system. Sell your grandmother, remortgage the cat, do whatever you have to do. Just don’t miss out.”

I didn’t promise any cats to the bank, but perhaps I would have if I’d needed to. My obstacle to playing Half-Life 2 was a pathetic lack of furniture: All I had in my studio apartment at the time was a futon, one Ikea chair, and a wobbly breakfast table that was too compact for a comfortable keyboard, mouse, and monitor arrangement. My Sony desktop PC, Logitech peripherals, and tiny LCD display instead lived on the floor under a window, flanked by a radiator that worked in tandem with the meager heat output of my early-2000s GPU to keep me warm.

If there was a good reason I was living like a disgraced detective in November 2004, it’s been compressed in my memory to ‘I was in college.’ Maybe I spent all my desk money on Half-Life 2. Whatever the case, after setting up an account with a frustrating new service called Steam, I played through Half-Life 2 lying on my stomach with my neck bent at 90 degrees, as if posing for the ‘what not to do’ section of an ergonomics textbook. We did what we had to do, as Jim said.

20 years later, I’m proud to say that I now own a desk, but I like to think it hasn’t changed me. Half-Life 2 certainly did, though, and along with Steam it set a new course for PC gaming. To celebrate the big anniversary of Valve’s landmark shooter, we’ve republished the original text of PC Gamer UK’s Half-Life 2 review below—enjoy the brief trip back to one of PC gaming’s most exciting moments. —Tyler Wilde, US Editor-in-Chief

Half-Life 2 review – PC Gamer UK, November 2004

It was all in that moment when I just sat back and laughed. I couldn’t believe it was quite this good. I chuckled in muddled disbelief, expectations utterly defied. My nervous fingers reloaded the level, knowing that I had to see that breathtaking sequence one more time. It was then that I knew for certain: Valve had surpassed not only themselves, but everyone else too. Half-Life 2 is an astounding accomplishment. It is the definitive statement of the last five years of first-person shooters. Everything else was just a stopgap.

Half-Life 2 is a magnificent, dramatic experience that has few peers.

Half-Life 2 is a near perfect sequel. It takes almost everything that worked from Half-Life and either improves on it, or keeps it much the same. But that simple summation undersells how the Valve team have approached this task. Half-Life 2 is a linear shooter with most of the refinements one would expect from years of work, but it is also a game of a higher order of magnitude than any of the previous pretenders to the throne. The polish and the stratospheric height of the production values mean that Half-Life 2 is a magnificent, dramatic experience that has few peers.

It would be madness for me to spoil this game by talking about the specific turn of events, so spoilers are going to be kept to a minimum. We’re going to talk about general processes and the elements of style and design that make Half-Life 2 such an energising experience. Key to this is the way in which Gordon’s tale is told. Once again we never leave his perspective. There are no cutscenes, no moment in which you are anything but utterly embedded in Gordon’s view of the world. Everything is told through his eyes. And what a story it is. Gordon arrives at the central station at City 17—a disruptive and chilling dystopia. And from there? Well, that would be telling. This is not the contemporary America that Gordon seemed to be living in during the original Half-Life. The events of Black Mesa have affected the whole world. The crossover with Xen has meant that things have altered radically, with hyper-technology existing alongside eastern bloc dereliction.

The world is infested with head-crab zombies and the aliens that were once your enemies now co‑exist amongst the oppressed masses. This very European city is populated by frightened and desperate American immigrants, and sits under the shadow of a vast, brutalist skyscraper that is consuming the urban sprawl with crawling walls of blue steel. It’s a powerful fiction. City 17 is one of the most inventive and evocative game worlds we’ve ever seen. The autocratic and vicious behaviour of the masked Overwatch soldiers immediately places you in a high-pressure environment. People look at you with desperate eyes, just waiting for the end to their pain, an end to the power of the mysterious Combine. Who are they? Why are you here? Who are the masterminds behind this tyranny? The questions pile up alongside the bodies.

Half-Life 2 isn’t big on exposition, but the clues are there. You’re thrust into this frightening near-future reality and just have to deal with it. Your allies are numerous, but they have their own problems. Your only way forward is to help them. And so you do, battling your way along in this relentless, compelling current of violence and action, gradually building up a picture of what has happened since Black Mesa. The Combine, the military government that controls the city in a boot-stamping-face kind of way, are a clear threat, but quite how they came to be and what their purposes are become aching problems. Once again Gordon remains silent, listening to what he is told so that you can find those answers for yourself.

But even with Gordon’s vaguely sinister silence (something that is transformed into a subtle joke by the game’s characters) there are reams of dialogue in Half-Life 2. It is spoken by bewilderingly talented actors and animated with almost magical precision. Alyx, Eli, Barney and Dr Kleiner are delightful to behold, but they only tell part of the story. There are dozens of other characters, each with their own role to play. And each one is a wondrous creature. They might be blemished, even scarred, with baggy eyes and greasy hair, but you can’t tear your eyes away. People, aliens and even crows, have never seemed quite so convincing in a videogame. Doom 3’s lavish monsters are more impressive, but Half-Life 2’s denizens are imbued with life. More importantly, they offer respite. Half-Life 2’s world is a high-bandwidth assault on the senses that seldom lets up. That moment when you see a friendly face is a palpable relief. A moment of safe harbour in a world of ultraviolence. As Gordon travels he is aided by the citizens of City 17 and the underground organisation that aims to fight the oppressors. Their hidden bases are, like the characters who inhabit them, hugely varied—an abandoned farm, a lighthouse, a canyon scrapyard and an underground laboratory—each superbly realised.

It is this all-encompassing commitment to flawless design that makes Half-Life 2 so appealing. Even without the cascade of inventiveness that makes up the action side of events, the environments become a breathtaking visual menagerie. Cracked slabs and peeling paint, future-graffiti and mossy slate, tufts of wild grass and flaking barrels, shattered concrete and impenetrable tungsten surfaces—City 17 and its surrounding landscape make you want to keep exploring, just to see what might be past the next decaying generator or mangled corpse. Whether you find yourself in open, temperate coastline or mired in terrifying technological hellholes, Half-Life 2 presents a perfect face. The first time you see ribbed glass blurring the ominous shape of a soldier on the other side, or any time that you happen to be moving through water, you will see next-generation visuals implemented in a casual, capable manner. Half-Life 2 doesn’t have Doom 3’s groundbreaking lighting effects, but objects and characters still have their own real-time shadows and the level design creates a play of light and dark that diminishes anything we’ve seen in other games. The very idea that people have actually created this world by hand seems impossible, ludicrous. The detritus in the back of a van, the rubbish that lies in a stairwell—it all seems too natural to have come about artificially. Add to this the split-second perfection of the illustrative music, as well as the luscious general soundscape, and you have genuinely mind-boggling beauty.

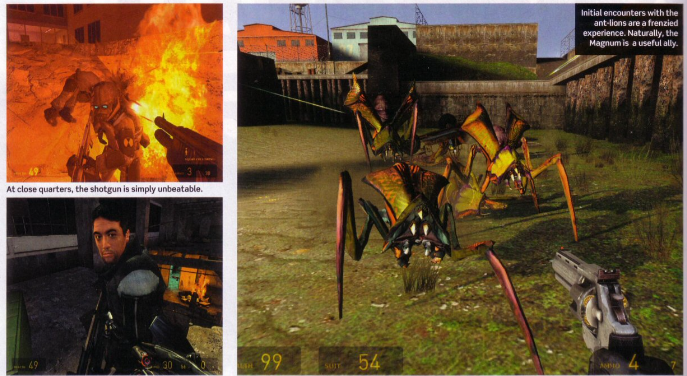

But these virtual environments are little more than a stage on which the action will play out. And what jaw-dropping, mind-slamming action that is. What’s tough to convey in words, or even screenshots, is just how much impact the events of combat confer. This is a joyous, kinetic, action game. The concussive sound effects, combined with the physical solidity of weapons, objects, enemies and environment, make this a shocking experience. Each encounter is lit up with abrupt and impressively brutal effects. Explosions spray shrapnel and sparks, bullets whack and slam with devastating energy. The exploding barrel has never been such a delight. You think that you’ve seen exploding barrels before, but no: these impromptu bombs, like everything else in the game, are transformed by the implementation of revelatory object physics. Unlike previous games, the object physics in Half-Life 2 are no longer a visual gimmick—they are integral to the action and, indeed, the very plot.

Gordon can pick up anything that isn’t bolted down and place, drop or hurl it anywhere you choose. Initially this consists of little more than shifting boxes so that you can climb out of a window, but gradually tasks increase in complexity. Puzzles, ever intuitive, are well signposted and entertaining. If they’re tougher than before they’re still just another rung up on what you’ve already learned. This is immaculate game design. There are a couple of moments in these twenty hours where something isn’t perfect in its pace or placing, but these are minor, only memorable in stark contrast to the consistent brilliance of surrounding events. There is always something happening, something new. You find yourself plunging into it with relish. Just throwing things about is immediately appealing. You find yourself restraining the impulse to just pick up and hurl anything you encounter. (Free at last, I can interact!) Black Mesa veteran Dr Kleiner is remarkably relaxed about you trashing half his lab, just to see what can be grabbed or broken. Combine police take less kindly to having tin cans lobbed at their shiny gasmasks.

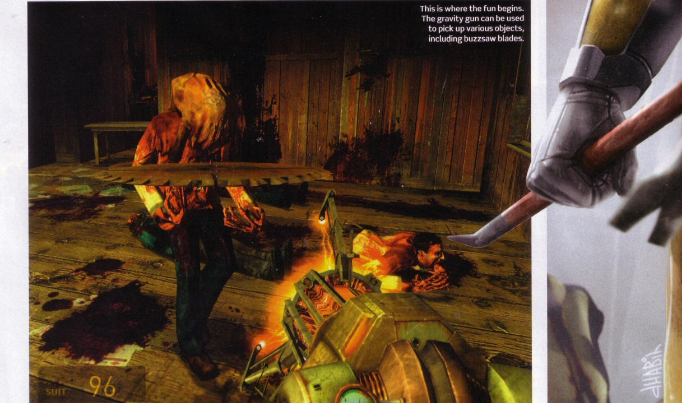

But the core process of this new physics, the key to the success of the game, is to be found in the Gravity Gun. Once you’ve experienced vehicular action and got to grips with combat, Half-Life 2 introduces a new concept—the idea of violently manipulating objects with this essential tool. The gun has two modes, one drags things toward you and can be used to hold, carry or drop them. The other projects them away and can either be used to smash and punch or, if you’re already holding something, hurl it with tremendous force. A filing cabinet becomes a flying battering ram, dragged towards you and then fired into enemies, only to be dragged back and launched again to hammer your foe repeatedly, or until the cabinet is smashed into metal shards. Pick these up and you can blast them through the soft flesh of your enemies.

The gravity gun isn’t just another a weapon, it’s the soul of Half-Life 2.

Killing the badguys with nearby furniture becomes habitual, instinctive. Or perhaps you need cover from a sniper—picking up a crate will give you a makeshift shield with which to absorb some incoming fire. Likewise, you immediately find yourself using the gravity gun to clear a path through debris-blocked passages, or to pick up ammo and health packs, or to grab and hurl exploding barrels at encroaching zombies, setting them ablaze and screaming. You can even use it to grab hovering Combine attack-drones and batter them into tiny fragments on concrete surfaces. Soon the gravity gun is proving useful in solving puzzles, or knocking your up-turned buggy back onto its wheels. Yes, a buggy. I’ll come back to that. The gravity gun isn’t just another a weapon, it’s the soul of Half-Life 2. Do you try to bodge the jump over that toxic sludge, or take the time to use the level’s physics objects to build an elaborate bridge? Do you waste ammo on these monsters or pull that disc-saw out of where it’s embedded in the wall? Of course, you always know what to do. When there’s a saw floating in front of your gravity gun and two zombies shamble round the corner, one behind the other, well, you laugh at the horrible brilliance of it. Yeah, I think that was the moment that I sat back and laughed. It’s just too much.

Sometime after these experiments in viscera comes Gordon’s glorious road trip. Simplicity incarnate, the little buggy is practically indestructible, but also an essential tool for making a journey that Gordon can’t make on foot. Dark tunnels, treacherous beaches and bright, trap-littered clifftops become the new battleground. Like the rest of the game there are oddities and surprises thrown in all the way through. The bridge section of this journey would make up an entire level in lesser shooters. And yet here it is, just another part of the seamless tapestry of tasks that Gordon performs. Also illustrative of the game as a whole is the way in which the coast is strewn with non-essential asides. OK, so you’re zooming from setpiece to setpiece, but do you also want to explore every nook and cranny, every little shack that lies crumbling by the roadside? Of course you do. This is a game where every hidden cellar or obscure air-duct should be investigated; you never know what you might find.

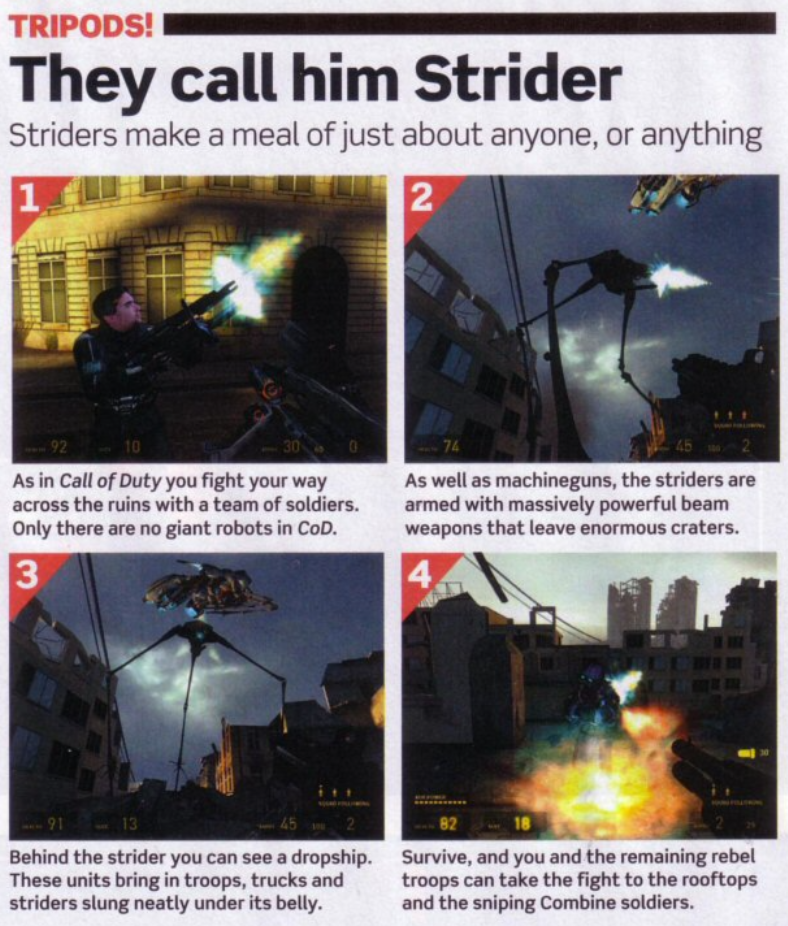

Investigating means using the torch that, oddly, is linked to a minor criticism of the game. Both sprinting and flashlight use are linked to a recharging energy bank. It’s clear why this restriction was imposed, but it’s nevertheless a little peculiar. The quality of the game meant that I was searching, rather desperately, for similar complaints. Smugly I assumed that my allies in a battle were non-human because that way Valve dodged the lack of realism and other problems created by fighting alongside human allies. Of course my lack of faith was exposed a few levels later, when I found myself in the midst of the war-torn city fighting alongside numerous human allies who patched me up, shouted at me to reload, apologised when they got in the way and fought valiantly against a vastly superior force. What a battle that was. I want to go back, right now. The striders, so impressive to behold, are the most fearsome of foes. Fighting both these behemoths and a constant flow of Combine troops creates what is without a doubt the most intense and exhilarating conflict ever undertaken in a videogame. The laser-pointer rocket launcher is back and even more satisfying than ever before. Rocket-crates give you a seemingly infinite resupply to battle these monsters but it’s never straightforward. Striders will seek you out, forcing you under cover, while the whale-like flying gunships will shoot down your rockets, inducing you to resort to imaginative manoeuvring to perform that killing blow. Even dying becomes a pleasure—you want to see these beasts smash through walls and butcher the rebels, again and again. Oh Christ, what will happen next?

I could talk about how those battles with the striders almost made me cry, or about the events that Alyx guides you through so cleverly, so elegantly. I could talk about the twitchy fear instilled by your journey through an abandoned town, or the way that the skirmishes with Overwatch soldiers echoes the battles against the marines in the original Half-Life. I want to rant and exult over this and that detail or event, this reference or that joke. I want to bemoan the fact that it had to end at all (no matter the excellence of that ending). And I’m distraught that we’ll have to wait so long for an expansion pack or sequel. I even had this whole paragraph about how CS Source will be joined by an army of user-fashioned mods as the multiplayer offering for this definitively singleplayer game. But we’re running out of space, out of time. There’s so much here to talk about, but in truth I don’t want to talk, I just want to get back to it: more, more, more… You have to experience it for yourself. This is the one unmissable game. It’s time to get that cutting-edge PC system. Sell your grandmother, remortgage the cat, do whatever you have to do. Just don’t miss out.