Follow along as I build a white gaming PC.

We test a lot of components at PC Gamer. We’re often swapping GPUs, CPUs, SSDs and RAM between test rigs to find out whether they’re worth your cash. Yet an important question to ask yourself when digging into the data is: “what’s it like to actually build a PC with this stuff?” To answer that, I’m actually building a PC with this stuff.

I’m putting together a gaming PC using some of the latest components around. You’ll find a parts list of what I picked and why, a build log covering the process of putting the PC together, and some reflections on what I’d do differently next time below. There will be a next time, too. You can catch all the PC builds from myself and the team in coming months, covering a range of budgets and form factors, right here on PC Gamer.

For this inaugural build, I’ve gone for one of the latest PC cases on the market, the Havn HS 420 VGPU, and stuffed it with the finest white components money can buy. This build is all about trying to distract you from actually playing any games on it and instead just staring wide-eyed through its panoramic window at the vertically mounted RTX 4080 Super and ludicrous CPU cooler within. It’s a beauty, but it wasn’t always. Much like I imagine Michelangelo had, at times, regrets about David’s nude frame, so too do I have some regrets here.

On that undeservedly big-headed note, let’s get on with the build.

The parts

Total: ~$3,231 | ~£3,021

If I’d have skimped out on any of the components within this case, I’d have angry PC gamers knocking at my door. You don’t get a chassis with a panoramic curved glass side panel and vertical GPU mounting to stick beaten-up old junk inside it.

No, that just won’t do.

Let’s start with the chassis. This is Havn’s HS 420 and it’s about as extravagant a dual-chamber case as you’ll find on the market today.

Havn is a new brand from Pro Gamers Group, which owns a few other notable brands in the PC hardware space: Ducky, Noblechairs, Aerocool, and ThunderX3, to name a few; and also major European retailers Overclockers and Caseking. The HS 420 is the brand’s first product and a company representative tells me it’s a completely custom design from the ground up.

There are two versions of the HS 420: the standard model for $199/£200 and the VGPU model for $269/£270. The latter offers an additional vertical GPU mounting bracket and 45 degree fan mount, and that’s the option I’ve gone with for this build.

I first caught a glimpse of this case on a rotating plinth at Pro Gamers Group’s booth at Computex 2024. Thankfully, it looks just as good in somewhat less luxurious digs, i.e. my office.

It’s a great candidate for a showcase build such as this as the glass side panel extends right across the front of the case uninterrupted—this is a fully panoramic PC case with a single sheet of glass carefully curved to fit the capacious chassis. You’d think that’d make for a clumsy PC case to install or remove parts inside but it all peels away with ease.

A handful of screws sit under the magnetic dust cover on the top and each panel can then be lifted off without any extra tools, exposing the entire inner frame for easy access. The rear and top panels also feature this excellent striped design, which is more than simple aesthetics, as each strip is cut-out of the panel to give this machine a little more room to breathe.

Stare inside this machine and you’ll find Gigabyte’s RTX 4080 Super 16GB Aero OC staring right back. Held aloft by a vertical GPU mounting bracket included with the HS 420’s VGPU version, this overclocked Aero graphics card’s fans sit unconventionally with fans facing the outside world. It’s an all-white design to match the Havn case and other components I’ve opted for here, and it looks really tidy.

The RTX 4080 Super sits as the apologetic follow-up to the far less popular RTX 4080—it’s fractionally faster and more affordable than the standard model. This Gigabyte design houses three capable fans, one of which spins in a different direction to the other two to reduce turbulence, and which will stop entirely when temperatures are below ~60° and during light load.

While the fans will whirr to life with a modern game running, generally this choice of GPU led to fantastically low temperatures and noise levels.

With a price of $1,150 / £1,026 / $1,846 AUD, the GPU is far from the cheapest option around. If you want to save pennies, check out our Black Friday graphics card deals page. That said, the model I’ve chosen here is one of very few all-white GPUs on the market, and it performs well. For that reason, it feels overpriced to me—not any more than the RTX 4080 Super does in general, anyways.

My choice of CPU is the unequivocally speedy Intel Core i9 14900K. Now, this chip has a shaky history with instability but it is one of the fastest gaming processors available today, even in light of the recent release of the Intel Core Ultra 9 285K.

I picked this 14th Gen chip for a couple of reasons: 1) I could use the Gigabyte Z790 Aorus Pro X with it—a capable LGA 1700 motherboard that looks very dashing in its white colourway; 2) Intel’s latest Arrow Lake chips weren’t widely available at the point I was building this system; and 3) I didn’t have an AMD 3D V-Cache chip to hand at the time. In an ideal world, I’d have the Ryzen 7 7800X3D in this build within Gigabyte’s X670E Aorus Pro X. This chip impressed in testing last year and I don’t have to worry about skyrocketing CPU temperatures and high power demands. Those are two areas where the Intel chip slips up. But it is very fast.

To combat the Core i9’s proclivity to chug watts like cheap beer, I picked the Hyte Thicc Q60 all-in-one liquid cooler. This comes with a 240 mm radiator and a high absurdity factor for the inclusion of an Android-powered screen. Yep, that’s practically a mobile phone on top of the cold plate, capable of displaying widgets programmed via the Hyte Nexus application, including album art or key temperature readouts.

The Hyte Q60 was a mistake. I can admit that in hindsight. I’ll detail this further in the build guide below, but if you’re considering the Havn HS 420 for your own PC build, I’d opt for a full 360 mm radiator and a cold plate without an enormous screen attached. That should be easy, there are next to no other coolers with such enormous screens attached.

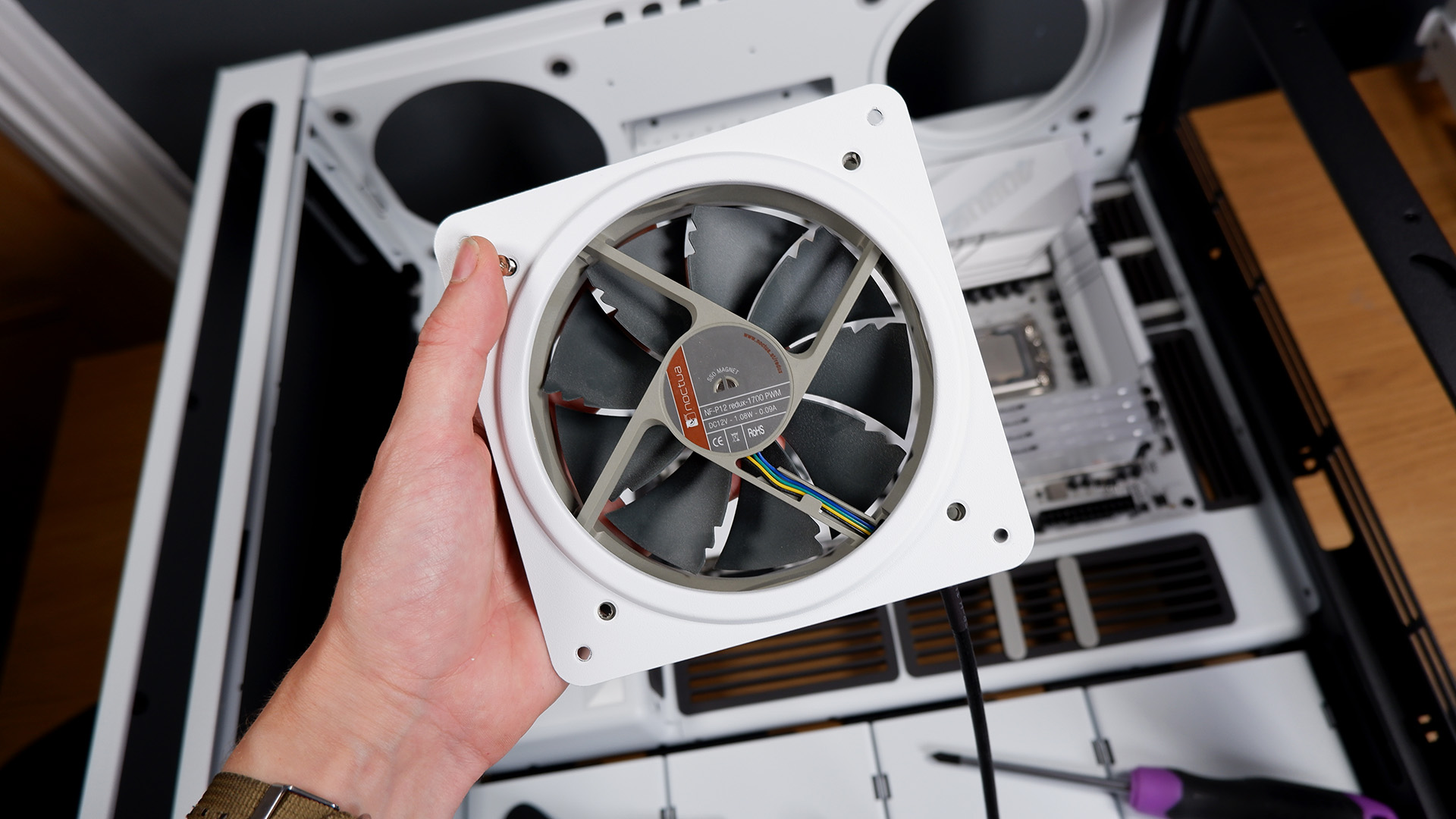

The Hyte Q60 does have one major benefit. It offers an easy way to connect system fans and RGB LED strips over proprietary magnetic connectors and USB Type-C. In fact, all except a pair of Noctua NF-P12 redux-1700 fans in this build were hooked up via a single cable run from the radiator and around the perimeter of the case. That’s three Thicc FP12 fans and three LS12 light strips using the control hub inside the all-in-one liquid cooler, which is a good way to save on messy cables.

I had to adjust my memory configuration due to the Hyte cooler: just two out of four sticks of the V-Color Manta XPrism 32 GB DDR5-6200 kit would fit alongside its screen. That won’t have any impact on the performance of this PC, however. The two DIMMs I was unable to install were only dummy sticks for uniform RGB effects—the capacity and speed remain the same.

The 6200 MT/s RAM kit hits a sweet spot for speed and latency with Intel’s 14th Gen platform. You can push for higher speeds but usually at a cost to latency or, well, actual cost. This Manta kit hits a CAS latency of 36, which is a healthy middle ground for available DDR5 kits.

For storage, I’ve opted for a single PCIe 5.0 NVMe SSD for this machine: Crucial’s T700. Rated to 12,400 MB/s sequential reads and 11,800 MB/s sequential writes, it’s no slouch. A PCIe 5.0 drive is overkill for most PC gamers right now and I’d absolutely recommend cutting this for a cheaper PCIe 4.0 drive to try to cut down costs with this build, but it means I don’t have to think about upgrading the boot drive anytime soon.

Lastly, the PSU. First, let me say I had hoped to use something different here, a more reasonable model with white cabling. It wasn’t available and I plucked this PSU out of my test bench to replace it. It’s not a sensible pick for this machine for two reasons: 1) it has a screen plastered on one side of it that won’t be in any way visible from inside the Havn’s second, rear chamber; and 2) it has more wattage than even this powerful PC requires at 1,200 watts. That’s huge and much better suited to an RTX 4090.

After receiving the last few parts in the mail, I was finally ready to assemble the PC. Looking forward to my colourful combination of cooler, RAM and GPU with wide eyed optimism. Of course, none of that went to plan, but that’s just the way it is with PC building sometimes.

The build

Step one: Remove the HAVN HS 420 VGPU from its cardboard container with incredible caution.

This panoramic glass case is one clumsy hand hold away from shattering into a thousand tiny pieces. Thankfully, it remains unshattered to this day, though it has come closer than I’d care to admit. I began this build by peeling off the tape and stickers adorning the HS 420 out of the box, pulling away every panel, removing the included accessories box, and preparing my build area.

Step two: Ready the motherboard.

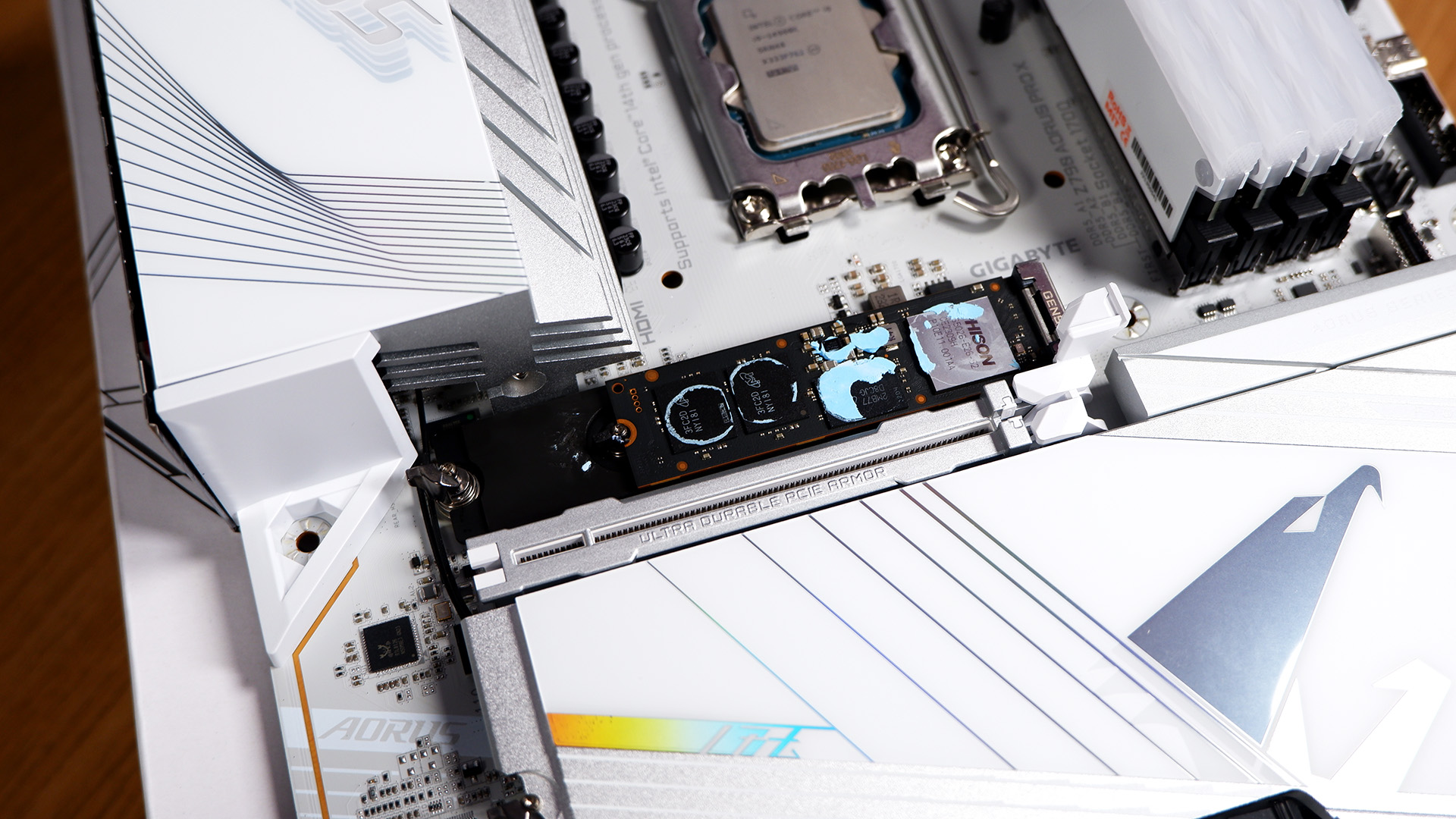

Placing the motherboard on top of the box it arrives in, I installed the memory, CPU, and SSD. This old trick saves time and effort later on in the process, though even more so for a build such as this. There’s not going to be easy access to this motherboard’s PCI slots, NVMe slots or internal headers once I install the VGPU bracket and graphics card, so best to get everything done right early in the build.

I installed both functioning DIMMs of the V-Color Manta memory into this motherboard alongside two dummy DIMMs. These are sticks fitted only with RGB lighting and intended solely to make memory look satisfyingly symmetrical. That’s a pretty desirable trait in a windowed case such as this. However, I don’t know it yet, but I will end up removing these DIMMs before the build is completed. They’re not compatible with the cooler, which is in turn not compatible with the VGPU mounting. It’s a whole thing.

The Intel Core i9 14900K slips into place snugly. I’ve not bothered adding any washers to the Independent Loading Mechanism (ILM) for this build, though if you’re using brand new parts I’d recommend it to prevent any bending that may lead to higher temps.

The Crucial T700 includes a chunky heatsink attachment. For this build, that has to go. A handful of screws detach the SSD from its housing and I only need to scrape a small amount of thermal padding away to reveal the naked NAND chips. One of the smaller features I’ve come to appreciate on the Gigabyte Aorus board is the tool-less access to the top NVMe slot. There are no awkward screws involved in the process whatsoever, actually, as both heatsink and SSD are held in place with easy latches.

With everything in place, the motherboard is screwed down into the HS 420. The case supports motherboards up to E-ATX but it’s best suited to ATX or smaller to make good use of the included cable channels.

Step three: Configure the cooling.

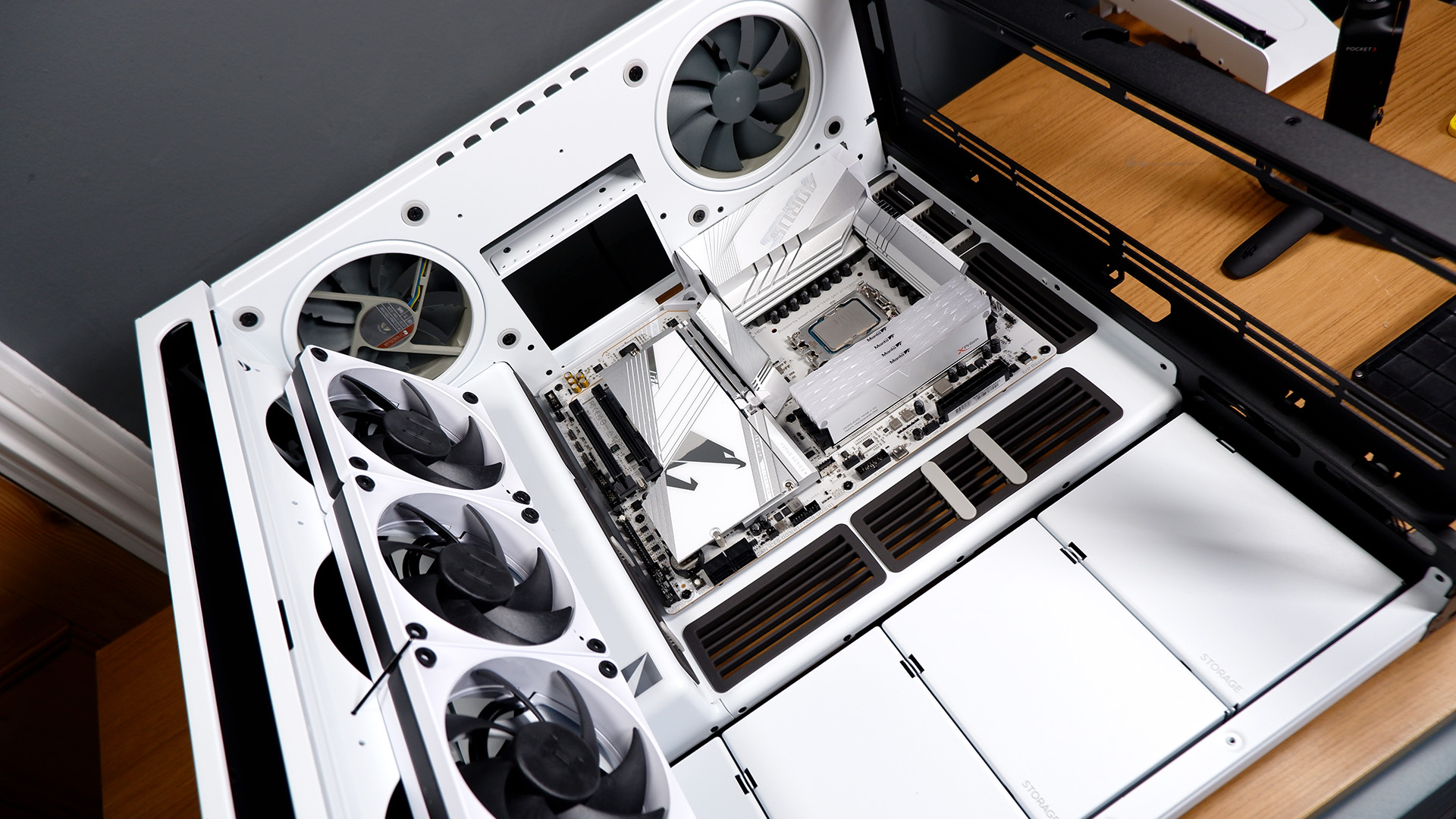

It’s a smart move to plan out your cooling ahead of time with the HS 420. This isn’t your average chassis and it relies on a bottom-to-top airflow, unlike most others that are front-to-back.

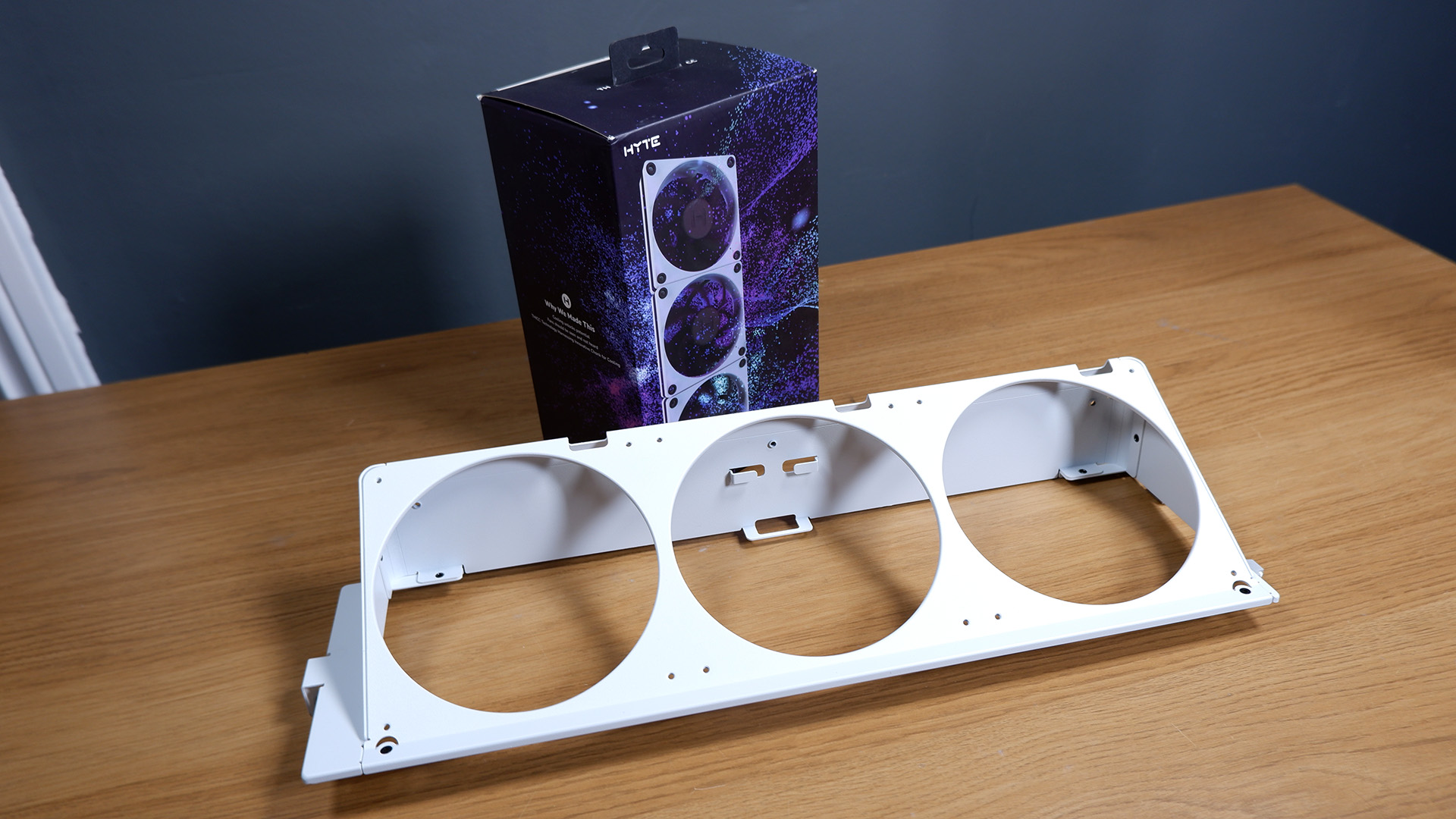

Don’t be like me. I opted for three 120 mm Thicc FP12 fans in the tilted mounting bracket in the bottom of the case—this is included in the VGPU version of the case and the standard version mounts the fans directly facing upwards—but I’m stuck having to zip-tie these in place for a secure fit. That’s because the VGPU bracket only supports three 140 mm fans. These Thicc fans magnetically connect to one another anyways, which saved the day, but don’t make the same mistake as I did.

Don’t install the fans backwards and only notice once you’ve started to install the GPU bracket, either. Definitely don’t do that.

I installed the Hyte Thicc Q60 CPU cooler into the top of the case. This job is made easy by the removable cooling bracket accessed on the HS 420, which leaves plenty of room between the cooler’s edge and the motherboard. There’s even plenty of space for the extra thick 240 mm radiator with two FP12 fans pre-installed. I switched these over to a push configuration to complete the chimney for this build.

I initially installed the Q60’s pump to the Core i9 14900K in a vertical position, as Hyte intended, though once I installed the VGPU bracket and graphics card, I had to admit defeat and rotate it sideways. That’s a bit of a shame, as Hyte is yet to offer a way to run the screen in horizontal mode. Hyte told me that may be a feature it includes in its Nexus software at some point—at the very least the ability to flip the screen’s orientation 180 degrees—though it’s not available right now. As such, I’d recommend a different cooler than this—a basic 360 mm model would be a much better pick.

I generally found the Hyte cooling set-up extremely useful for this build. In essence, it allowed me to connect the Hyte Thicc Q60 CPU cooler to the FP12 fans in the rear with only a single cable run—a braided, magnetically attached USB Type-C. Then, from the final fan in the three-fan chain, I ran another length of cable to the LS10 RGB lighting strips. That’s CPU cooling, case cooling, and lighting connected and synced via a single cable run.

Even without this sort of simplicity, the HS 420 includes two (yes, two) fan controller hubs for easy syncing of fan speeds.

To complete my cooling configuration, I have two Noctua NF-P12 redux-1700 fans. These are fitted into the included fan brackets, which are themselves removable from the case for easy installation. One sucks cool air into the case closer to the bottom, beneath the GPU intake, and the other expels hot air out just beyond the VRM and CPU. These are both hooked up into one of the fan controllers, which is duly connected to my motherboard’s CPU fan header.

Step four: Connect those cables.

I unravelled the front panel connectors neatly included in the rear of the HS 420 and connected them to the motherboard’s USB, audio and front panel connectors. It’s important to do this now, as otherwise I’d have a very hard time trying to connect these once the GPU is in place. Form over function at its finest. But hey, the GPU looks fantastic when mounted this way.

I turned my attention to the rear of the HS 420 to install the PSU, Gigabyte’s Aorus P1200W. I needed this PSU’s wattage for this machine—the alternatives I had available to me were a little on the small side—but I have to admit the PSU’s unique selling point, a full-colour screen, is entirely wasted. The HS 420’s dual-chamber design means you can’t see the PSU at all.

Thankfully, the PSU is easily loaded into the trunk on the HS 420, and there’s ample room for cables.

I only need to run the motherboard, CPU, and PCIe cables for this build. Though a spare SATA is handy to have ready for any later expansion. I also needed a spare PCIe 6-pin connection for the Hyte cooler to connect to.

The wide cable management channels that run from the bottom to the top of the case, around the motherboard, and through the top and rear panels are simply superb. I soundly stuff each one with each of the cables as I go, strapping them in place, and taking them where they need to go. I was not neat about it, but that doesn’t really matter, as they all fit snugly in the generous cable management system.

Step five: Mount the GPU.

The highlight of the build has to be the vertically mounted graphics card. An RTX 4080 Super with a fresh white paint job will occupy most of my eyeline once installed, but I had to make sure not to mess it up before I got there.

First, I need to install the vertical mounting bracket. This is easily done, as I had to remove it following the same steps but backwards in the beginning to make way for the motherboard. I started by connecting the PCIe 5.0 riser cable, as it’s a little more fiddly to attach once the rest is installed. Then I slid the bracket into place. This is held on with a couple of screws, though this bracket is adjustable to different depths, and requires a couple of thumbscrews as well. With this securely tightened into place, it was a surprisingly simple job to mount the extremely large Gigabyte Aero graphics into place.

Except for the screen mounted on top of the cold plate on the CPU. That was an issue. I ended up having to spin the cooler to accommodate the long screen, which meant the arm holding the screen in place sat overtop the RAM. That then meant I had to ditch the closest DIMM to the CPU socket, one of my two dummy DIMMs, and I wasn’t going to keep the other around in that case.

So the dummy DIMMs were gone, and the screen on the cooler was the wrong way around, but at least the graphics card was sitting pretty.

With my CPU cooler reoriented, my only other concern was that the graphics card brushes up against a piece of glass used to direct air away from the backside of the GPU and across the intake fans. I was mostly concerned about vibration creating excessive noise, though in my testing I didn’t come across anything noticeable. Still, I did test thermals with both the glass included and removed, and both times temperatures stayed near-enough the same. So I wouldn’t worry about ditching it altogether.

Step six: Reassemble.

One final check over and I’m ready to reassemble the side panels. That means checking each cable, connection, and fan orientation. That last bit is extremely important if, like me, you realise you put the entire bottom row of fans in the wrong way around. Luckily, magnetically attached fans with only a handful of screws in them make for an easy switch.

Then, on with the dust filters and panels. The HS 420 comes with a large dust filter for the underside intake, though I was surprised to see a compact single-fan dust filter included for the rear lower intake, too.

One addition I made at the last minute with this build was a little bit of black electrical tape along the lower edge of the curved panel. Some might disagree with this sorta thing, but I feel the black tape is a neat way to cover up the RGB LED strips I’ve run along the bottom of the case. If these light strips were diffused, maybe I’d not bother with the tape, but seeing as the LS10 is bare LEDs, I prefer to cover up the strips themselves.

Step seven: Plug it in and press the button.

With every panel now back on the chassis, I hit the power switch on the PSU to give this PC a test run.

So… did it post right away?

The performance

This PC posted right away. Phew. It booted into the BIOS screen where I promptly installed the latest version to stave off any concerns of instability with this 14900K.

With Windows 11 installed and fully updated, it’s time to play some games and get an idea of this PC’s performance.

The RTX 4080 Super delivers superb frame rates in combination with the Core i9 14900K. That’s hardly surprising but it is incredibly satisfying to game on nonetheless.

I carry out all gaming tests at 1440p, which offers a happy medium of frame rates upwards of 100 fps in Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora and Metro Exodus Enhanced Edition. With DLSS and Frame Generation enabled, I am able to hit over 100 fps in Cyberpunk 2077, too.

The most impressive feat is that throughout my testing, the GPU keeps extremely cool. During a pretty lengthy three run test of Metro Exodus Enhanced Edition, which I use to measure thermals while gaming, I saw the GPU temperature peak at 60°C only, with an average of 57°C. This seems pretty spectacular, so I’ve dug into the data collected using Nvidia’s Frameview tool in the other games tested to find out more.

Yep, the GPU never exceeded 60°C in any other game. In fact, there are Baldur’s Gate 3 runs where the average temperature is in the mid-forties. That’s a real win for the cooling solution both on this card and inside the Havn HS 420.

It should come as no surprise that an overkill rig such as this is able to shred through Cinebench R24, 3DMark, and various productivity and encoding benchmarks with ease. Though I am a little surprised to see high CPU temperatures from the Thicc Q60 liquid cooler. The Core i9 14900K is often too hot to handle with intensive workloads, as evidenced here.

I’d wanted to keep my chip from hitting 100°C at all costs, but unfortunately it isn’t to be. Another reason why a bigger CPU cooler might be a smart decision.

I can report healthy VRM and SSD temperatures, even from that PCIe 5.0 SSD. These are notoriously hot drives and I had thought this might prove an issue after removing the heatsink included by Crucial and relying on the Gigabyte Z790 Aorus Pro X’s instead. However, the motherboard keeps the drive’s temperatures well and truly in check, even throughout the 3DMark Storage benchmark.

The conclusion

I won’t wax lyrical about this build’s top performance too long—that’s a little bit too much like patting myself on the back for a job well done. And evidently, some things didn’t go quite as planned. Though I will wrap up with a couple of reflections on what went right, what went wrong, and where I’d do things differently next time.

The case was a huge success. I don’t regret for a second opting for the vertical GPU mount, even though it makes changing out an SSD or plugging in an internal USB header an absolute nightmare. It’s all worth it for the overall finish of the build, which I still haven’t got sick of staring at as of yet. Sadly, I have to take it all apart before I will.

Though I do wish I’d been able to get the correct size fans for the mount included with the VGPU. Similarly, I should have been more aware of the size constraints for the CPU cooler, screen, and RAM. I was blissfully unaware of the clearance issues until I was face to face with them, which led to a couple unfortunate misses, such as being unable to use the screen to its fullest potential or sticking a couple extra DIMMs in the machine just for extra style points.

Though I cannot fault it for overall style and performance, there are ways I could have levelled it up further, such as with white sleeved power cables or a PSU that supports a native 12×6 power connector. Also not using a PSU with a very expensive and unnecessary additional screen when you know it’s going to be hidden in the back of the case would be a start.

Honestly, I got lucky a few times with this build, a few less fantastical parts and a few more reasonable parts would’ve saved me a lot of hassle. But it all actually worked out, this time. Perhaps the moral of the story is to not get too carried away with ideas—I foolishly wanted a screen and a vertically-mounted GPU within one mid-tower PC case—or just to roll with the punches when it doesn’t all go quite right. Either way, this remains one of the loveliest gaming PCs I’ve ever built, and I’m glad I did.

Now, to take it all apart and start again fresh next month.