You taught an AI to play chess? Great. Now teach it to run a Dungeons & Dragons 5th edition campaign in the Planescape setting using the 2024 rules.

In 2018, a group of grad students at Georgia Tech published a paper that noted games had often been “an important testbed for artificial intelligence” in the past. AIs have been beating us at chess, checkers, and Unreal Tournament for years, after all. Since that was the case, they argued, it makes sense for future testing of AI to focus on whether they could learn to play tabletop roleplaying games. Games like Dungeons & Dragons would serve as an effective measure of the progress of AI, “due to an infinite action space, multiple (collaborative) players and models of the world, and no explicit reward signal.”

What they didn’t predict was how controversial AI would become by the time that was possible—a topic we’ll come back to later.

In 2019, OpenAI released GPT-2, a large language model trained on eight million web pages that could generate narrative responses to short prompts. Though it wasn’t fully released until November, a partial version was available by February, and three months later had already been used to create the first version of AI Dungeon.

Though more of a text adventure than a roleplaying game, AI Dungeon was an early taste of what it would be like to have a computer for a Dungeon Master. While the results typically descend into the surreal if not outright nonsensical, it made a fine proof of concept. Players were soon trying to craft the perfect prompt to turn GPT-2 into a DM, whether by creating opuses over 1,000 words long, or crafting something that took less than 100.

Problems emerged with both approaches. The chatbot DM would often try to wrap up an entire combat in a single reply rather than letting you play it out blow-by-blow. It would forget what had happened if you played for too long, and was averse to roleplaying conversations. It would take more than just a well-written prompt to create an artificial DM.

Professionals stepped in, and now there are several alternatives to choose from, like Hidden Door, which promises to let you play a story in the world of Wizard of Oz, Call of Cthulhu, or The Crow thanks to its use of “a unique architecture” and officially licensed source material. The end result has been underwhelming in my experience—stories hop from one disconnected scene to another in a dreamlike fashion and actions flip-flop back and forth. In one Call of Cthulhu game I was chased by a cloaked figure who I managed to escape from, then be caught by, then escape from, then be caught by all while gaining and losing and gaining and losing a pocketwatch in a tedious process of back-and-forth indecision on the narrator’s behalf.

Examining a wooden box in Hidden Door’s Call of Cthulhu game. (Image credit: Hidden Door)

For a more traditional game of Dungeons & Dragons in digital form, there’s Friends & Fables. Created by William Liu and David Melnychuk of indie game studio Side Quest Labs, Friends & Fables comes with character sheets, XP-tracking, an inventory, illustrated NPCs, and a narrator nicknamed “Franz” who acts as game master.

“It’s not just one chatbot that you’re talking to,” Melnychuk tells me. “It’s more like a system where there’s one part of the AI GM that reasons about, like, is something new introduced? If there is, we need to save that to the game state—or do we need to update it? Things like that, it’s a bunch of different modules that come together to create the final outcome that you see when you play.”

The funny thing is, while Liu and Melnychuk needed to train their large-language models with examples so it knows when to add an item to the inventory (Friends & Fables mainly uses Llama), it already knew the rules of D&D 5th edition. “A lot of these large language-based models, they’re actually trained on pretty much the entire internet,” Melnychuk says. “They have a lot of just general knowledge about most things. That includes D&D and the SRD.”

“The rule set, Wizards of the Coast has published it under the OGL and Creative Commons,” Liu adds. “So it’s on the internet for these language models to Hoover up.”

OK Computer

Adventurers try to fly a spaceship in Expedition to the Barrier Peaks. (Image credit: Wizards of the Coast)

When I play Friends & Fables, it certainly feels like a classic game of D&D. I start at an inn, with Franz describing several NPCs I could talk to. One of them has a lead on a magical artifact worth stealing, but wants to meet somewhere more private to discuss it. That leads to a journey into the tunnels beneath the city where a group of wizards have been meeting to conduct magical experiments on the sly. Along the way there are skill checks and back-and-forth dialogues with an insulting barbarian and a curious bard. It feels like exactly the kind of game of D&D an eager beginner might run.

One off-note is that Franz seems to be obsessed with the phrase “intricately carved wooden box,” introducing more than one unconnected wooden box into the story with the same phrasing every time. When I bring this up Liu asks if I met anyone named “Elara”, and I tell him I did learn about a goddess with that name. Turns out, that’s another thing Franz keeps falling back on.

“The way that these language models work is that they’re doing next-token prediction,” he explains. “They’re spitting out the sentence, and they’re getting to a point—and a token is just like a word, or a string of words or characters—and so it’s trying to guess, ‘What is the most likely next one?’ It’s not that those are the only names that were in the training data, but that those are the ones that end up having the highest probability to be the next token.”

Accepting a quest in Friends & Fables. (Image credit: Side Quest Labs)

Friends & Fables is still in beta, he points out, and “we’re definitely working on fixing some of those things.” Even with oddities like these—players on the Discord server have cataloged other Franz favorites, like windmills and hooded figures—my experience was more sensical than the amusing oddness AI Dungeon rapidly descends into.

“If we’re being completely honest,” Melnychuk says, “I think if AI Dungeon met our expectations of what we were expecting from an AI game we probably would have never built Friends & Fables.”

Their motivation comes from a familiar story: the difficulty of getting an RPG group together in real life. “I have a couple of friends who play a lot of D&D,” Liu says, “but they were deep in their own campaigns and I didn’t feel like I could ask to just join after they’re, like, three years deep. I also didn’t really feel like just going out and finding a group for myself, of strangers.”

Bardo is another AI GM—one that lets players upload their own rulebooks. (Image credit: Bard Studio)

It’s a tale as old as D&D itself. Even now, with roleplaying at the height of its popularity, people struggle to find or maintain a campaign that suits them. “We get people that pop up in our Discord all the time who tell us, ‘This is so great because I have two kids now, and don’t have time to play,'” Liu says. “Or there’s one guy who told us—he lives in Iraq, and there’s just, like, nobody to play with there. He has a real hard time if he wants to play, so this was a solution for him. Just hearing people tell us that we’re kind of solving this accessibility challenge for them is why we kept doing it.”

Both are at pains to explain they’re not interested in replacing human DMs, but rather in supplementing them. As well as providing a substitute for people who can’t find a game, they want Friends & Fables to be able to help DMs run their own games.

“Think of it as a super-powered group chat,” Liu says, “where you’re the DM and you could send a message and say, like, ‘Jody’s character, roll a skill check.’ Then a button on your phone pops up, and then you hit the skill check, right? That’s definitely part of the future vision, but we’re not there yet.”

Ethics & Electronics

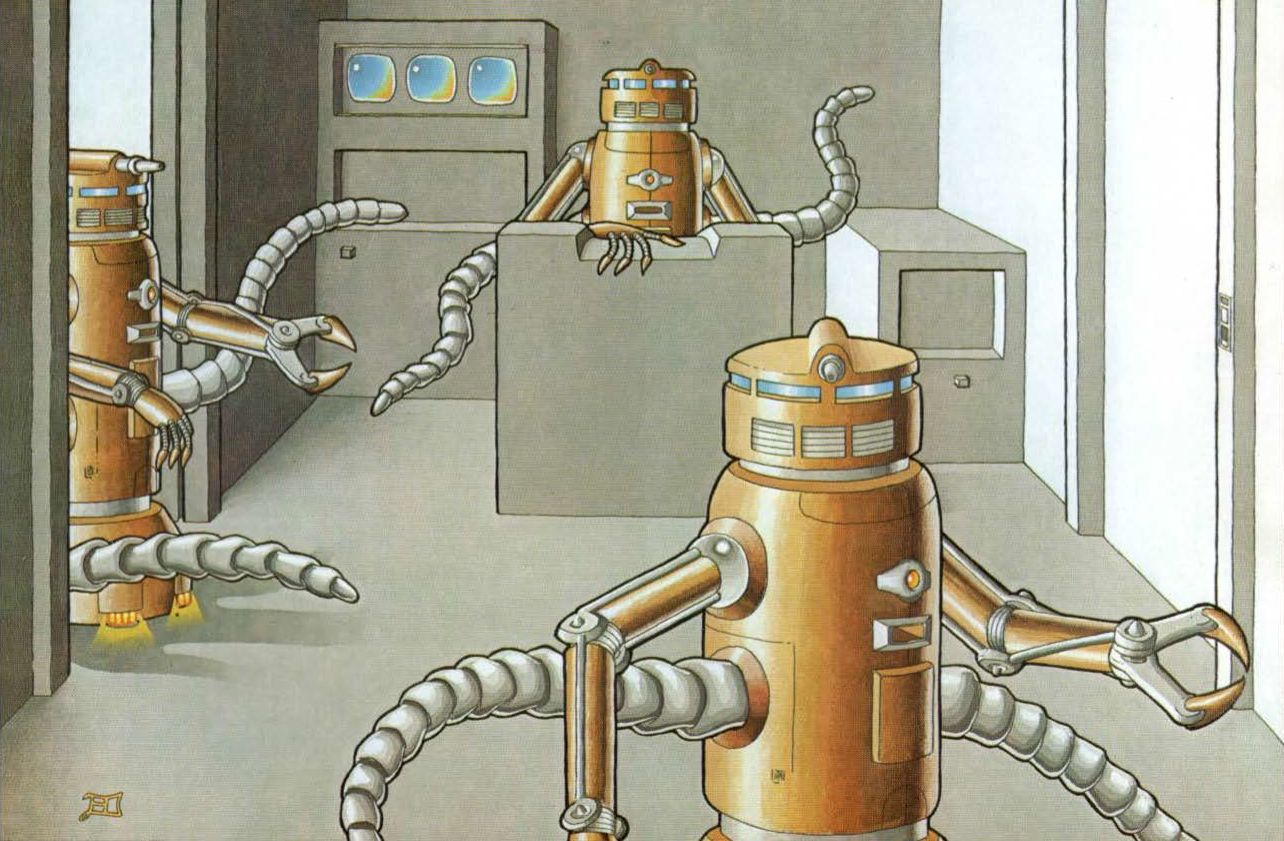

Robots in the 5th edition update of Expedition to the Barrier Peaks. (Image credit: Wizards of the Coast)

Who hasn’t, in a moment of writer’s block, turned to an online fantasy name generator? If an AI helps me run a game, is it any different to recycling bits of a pre-written scenario or showing my players NPC art I found by doing a Google image search for the phrase “elf pirate”? I use third-party stuff when I roleplay because I don’t have time to do everything—my players don’t need to know how often I steal NPCs from Brennan Lee Mulligan—and it doesn’t make the games I run any less satisfying.

Still, AI has been a hot-button topic in the pen-and-paper RPG community. D&D publisher Wizards of the Coast came under fire for using AI-generated art, and though it swore off it, the CEO of its owner Hasbro has been much more chipper about embracing AI. Hidden Door CEO Hilary Mason has spoken at length about the ethical problems that come with generative AI, telling PC Gamer last year that the company is committed to using ethically sourced training data and paying authors.

“We want writers to get paid,” said Mason. “We see what we do as a way of giving writers access to the technology that takes the work they’ve already done—all of that world building, all of that imagining, all of that writing—and then gives them another way to share that with their fans where they get paid more for the work they’ve already done. We’re really excited to work with writers. And personally, I know this is controversial, but I don’t think AI is innately evil. I think what we’re arguing about is who gets to benefit, and we really want to see the writers, the creators, benefit from it.”

Character selection in Friends & Fables. (Image credit: Side Quest Labs)

To generate art for its characters and locations, Friends & Fables relies on Stable Diffusion—a deep-learning model that has been criticized for using a data set of publicly available images without the permission of their creators, which is why Getty Images filed a suit against it. “We totally sympathize with creators and artists who have gotten their data essentially trained on without permission from all these big AI companies,” Liu says. “We don’t think that’s right either. Like, we think artists should be compensated.”

He compares their use of Stable Diffusion to the way a DM running a home campaign might. “AI art generators unlock some really cool things there where you can’t really hire a sketch artist to come to every campaign and draw things out for you on the fly,” he says. “That’s just not possible.” Friends & Fables isn’t just a home campaign, though. While you and one friend can play free for a while, eventually you’ll run into the paywall.

Whether or not there’s profit involved, generative AI’s biggest critics won’t touch it on the basis that it relies on stolen work, devalues real artists, and generates hollow mush. On the other side are people who enjoy refining prompts and finding the specialized use cases where AI can excel as an assistant rather than a replacement. The role of generative AI in RPGs is being explored and developed at dining room tables, tech startups, and big companies like Nvidia (which has been experimenting with conversation-holding NPCs), regardless of the ethical and legal battle lines having already been drawn, and both sides of the culture war using it as another way to holler at each as predictably as anything AI could come up with.