SAG-AFTRA actors will refuse to work for Activision, EA, Take-Two, and other major developers until they get protection from AI exploitation.

It’s happening again: Videogame voice and motion capture actors in the SAG-AFTRA union are going on strike. Over 160,000 performers will refuse to work on games in production at a number of major developers, including Activision, Disney, and EA, until the companies agree to a contract with “critical AI protections” for union members.

The strike officially begins on July 26.

“Although agreements have been reached on many issues important to SAG-AFTRA members, the employers refuse to plainly affirm, in clear and enforceable language, that they will protect all performers covered by this contract in their AI language,” says the union.

The voice actors, who authorized the strike with a 98.32% “yes” vote, want big game makers to inform the union when they plan to use generative AI in a way that would replace the work of actors, and to negotiate compensation when they want to generate material based on an actor’s voice or likeness.

The fear is that without sufficient protections for voice actors, game companies will cut costs by training AI systems on their work, allowing a developer to, for example, endlessly reproduce an actor’s voice without hiring them to record new lines.

“Eighteen months of negotiations have shown us that our employers are not interested in fair, reasonable AI protections, but rather flagrant exploitation,” says actor and union negotiator Sarah Elmaleh. “We refuse this paradigm—we will not leave any of our members behind, nor will we wait for sufficient protection any longer.”

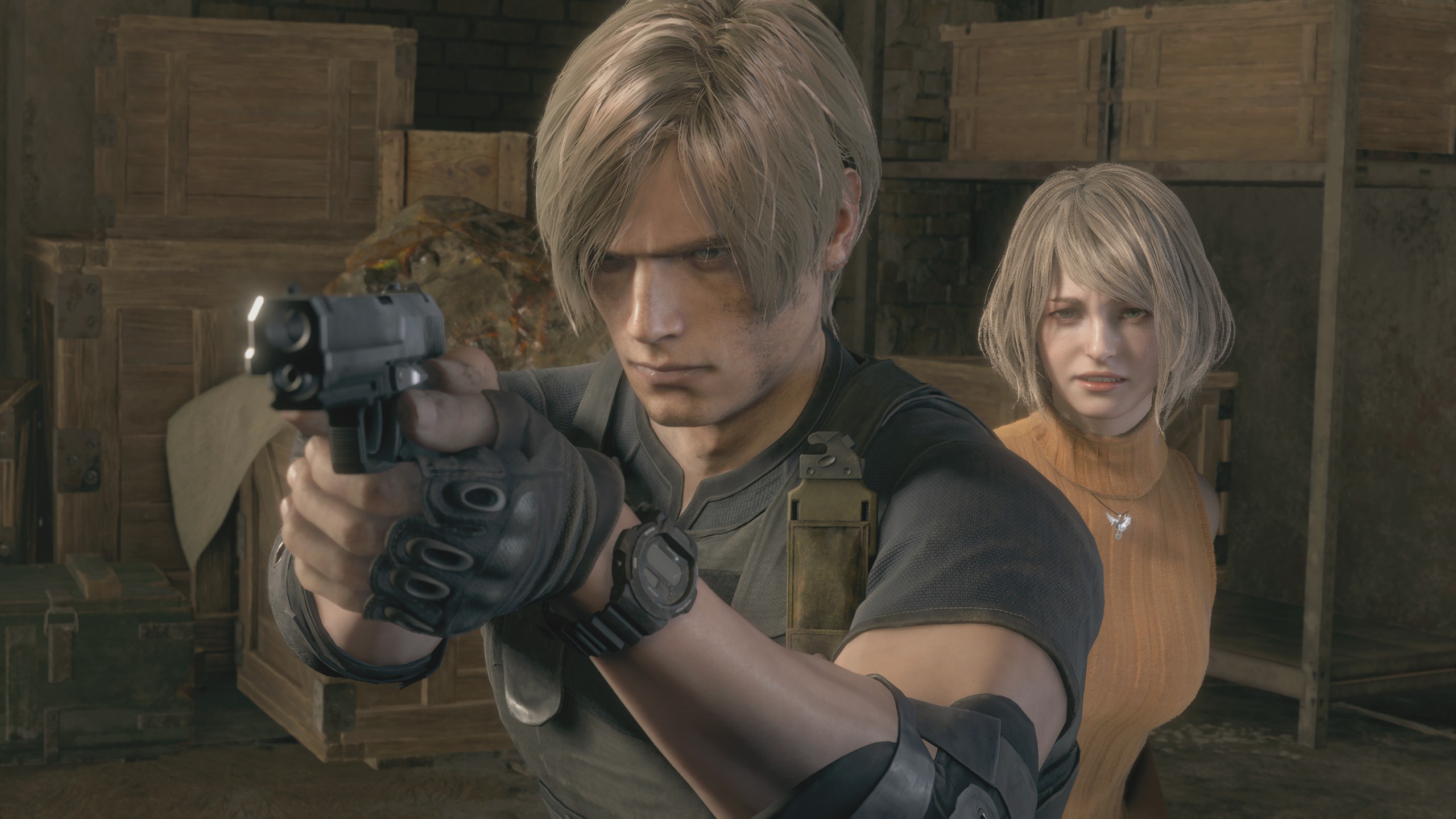

Generative AI voices will arguably never be able to perform as convincingly as real actors, but they have already proven a threat to voice actor livelihoods. Free-to-play FPS The Finals, for instance, uses AI text-to-speech software for its commentators rather than voice actors, and it’s far from the only game to do so.

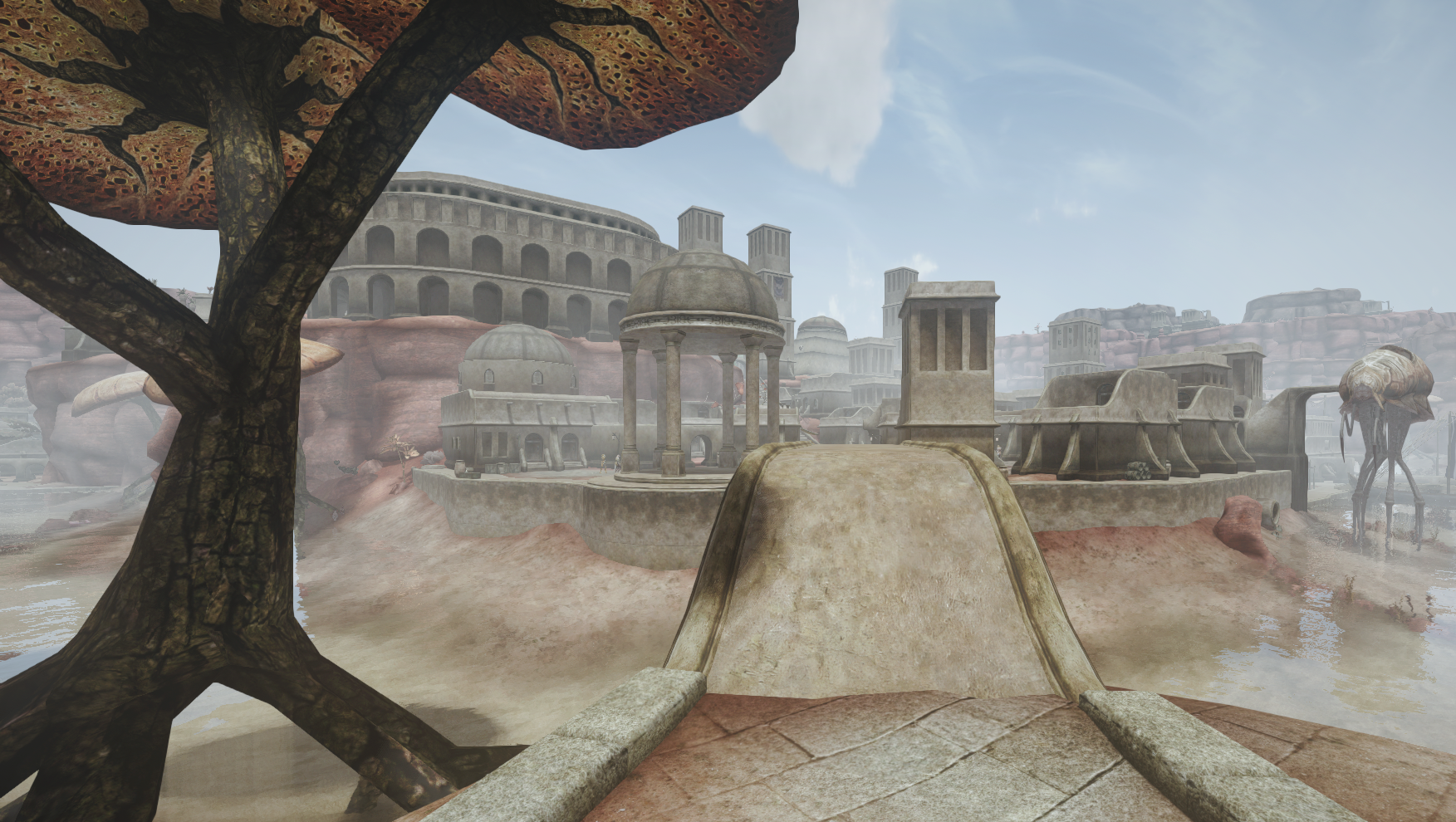

There are also examples in the wild of real actors having their voices replicated—Stellaris uses generative AI voices based on the voices of actors, for instance, although Paradox pays royalties to the actors who provided the AI training material, which is the kind of agreement a contract with AI protections can require.

This new frontier of generative AI use can get very messy: One notable incident saw OpenAI use a voice that sounded very similar to Scarlett Johansson’s, mimicking the Hollywood star’s performance as an AI companion in the movie Her. The company said that it was not Johansson’s voice, but removed it “out of respect” for the actor when she complained.

AI voice generation and replication is also being used by non-professionals, in some cases to create material that actors vehemently object to, such as pornography. It’s hard to stop hobbyists, but contractual protections could at least prevent game companies from exploiting an actor’s likeness in work they didn’t agree to.

The actors are striking for “fair compensation and the right of informed consent for the AI use of their faces, voices, and bodies,” says SAG-AFTRA national executive director Duncan Crabtree-Ireland. AI was also one of the issues that motivated SAG-AFTRA and Writers Guild of America strikes on Hollywood studios in 2023.

SAG-AFTRA videogame actors last went on strike in 2016 over residuals. That strike, which targeted the same set of companies, lasted for nearly a year. It isn’t obvious how significantly it hindered in-development games at the time, as big developers wouldn’t have publicly attributed delays to the strike, but one notable consequence was that actor Ashly Burch did not reprise her role as Chloe in Life is Strange: Before the Storm.