It's a shame that we'll probably never get to see a truly massively capable APU but I'll never stop dreaming.

(Image credit: Future)

This month I’ve been testing: Gaming mice and Elden Ring. Two things which haven’t normally been of great interest to me, but the former has shown that they’re no longer awkward, niche things and are genuinely great to use. The latter is still the same as it’s ever been, though, for better or worse.

AMD is well and truly on top of its game. Want the best gaming CPU possible? Get an AMD Ryzen 7 7800X3D. Need to throw lots of cores at a rendering project? Use an AMD Ryzen 9 7950X or a Threadripper Pro 7995WX, if money isn’t an object. The same is true for servers, AI mega-computers, consoles, and handheld gaming PCs—AMD rules the roost. And yet with its forthcoming Zen 5 chips, AMD is also driving an increasingly larger wedge between the CPUs it has for mobile platforms and those for the common desktop PC.

Just a few years back, the only significant differences between a Ryzen CPU in a laptop and one in a desktop were the number of cores, clock speeds, and amount of L3 cache. These were typically all lower for mobile chips to keep the chip smaller and help keep it within a certain power budget. The cores themselves, though, were exactly the same between the two.

Take AMD’s Z1 Extreme chip in the Asus ROG Ally. That has eight cores, 16 threads, a boost clock of 5.1 GHz, and a power limit of 30 W. Each of those cores is precisely the same Zen 4-powered core that you’ll find in a Ryzen 9 7950X, a Threadripper Pro 7995WX, or even an Epyc 9654. They just share a smaller amount of L3 cache.

But when AMD developed Zen 4c, a compact version of the ‘normal’ Zen 4 core, things started to change. For example, the original Ryzen 5 7540U laptop APU had six Zen 4 cores inside it, but then the chip giant updated it so that four of those cores used the Zen 4c architecture.

“No human being would ever know the difference,” AMD claimed, but that’s not entirely true. The Zen 4c cores don’t boost as high as the Zen 4 cores.

However, In terms of instruction throughputs, latencies, and capabilities, there’s no difference between them. It’s a fundamentally different approach to Intel’s hybrid CPU design, where the P-cores and E-cores are not very similar at all.

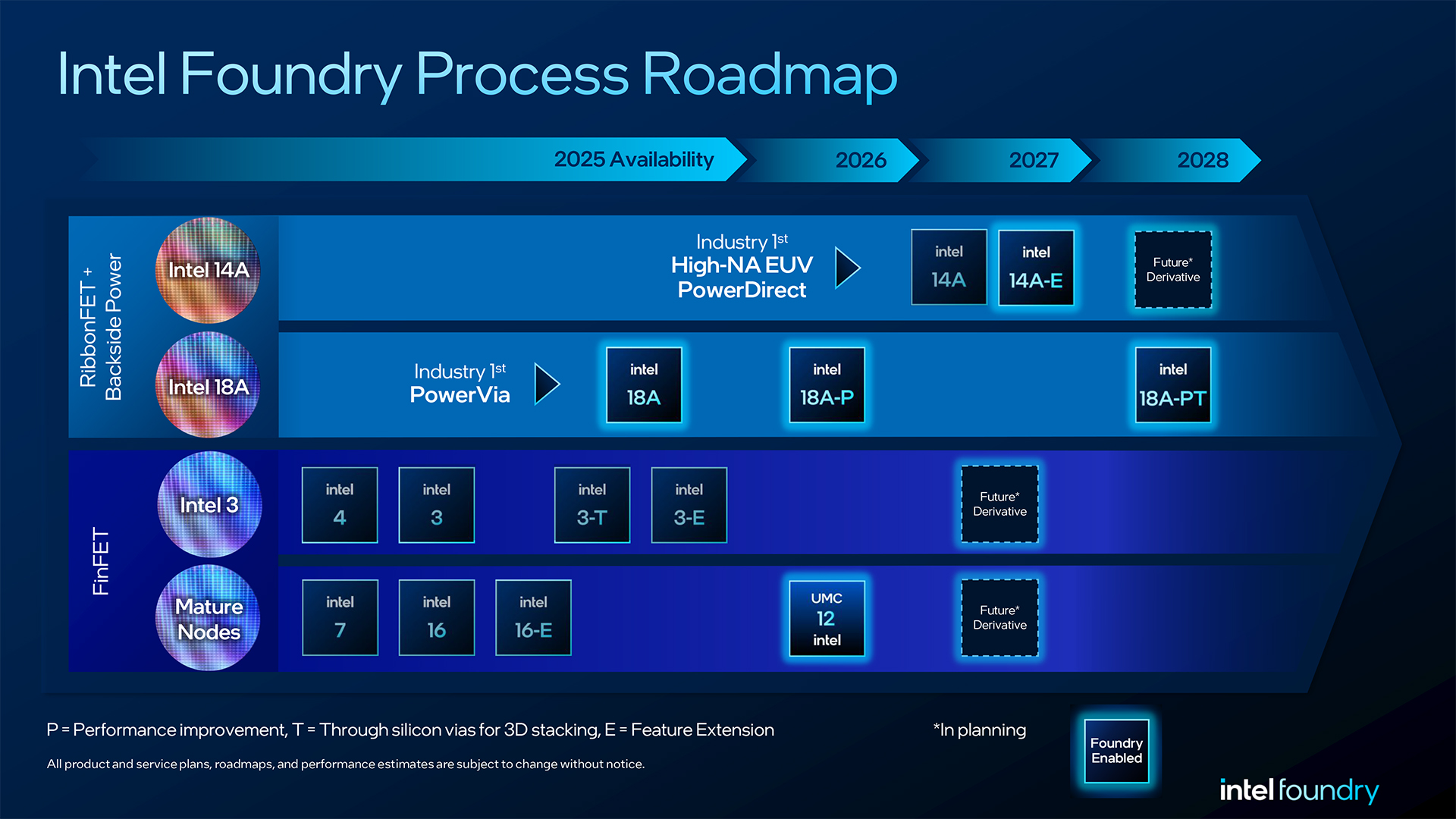

With the forthcoming Strix Point APUs (and possibly the hulky Strix Halo ones, too), AMD seems to be shifting a little more toward Intel’s way of thinking. The Ryzen AI 9 365 boasts 10 cores, with four of them being Zen 5 and the remaining six being Zen 5c. Nothing wrong with that, of course, except that the former gets to share 16MB of L3 cache, whereas the latter has to make do with just 8MB.

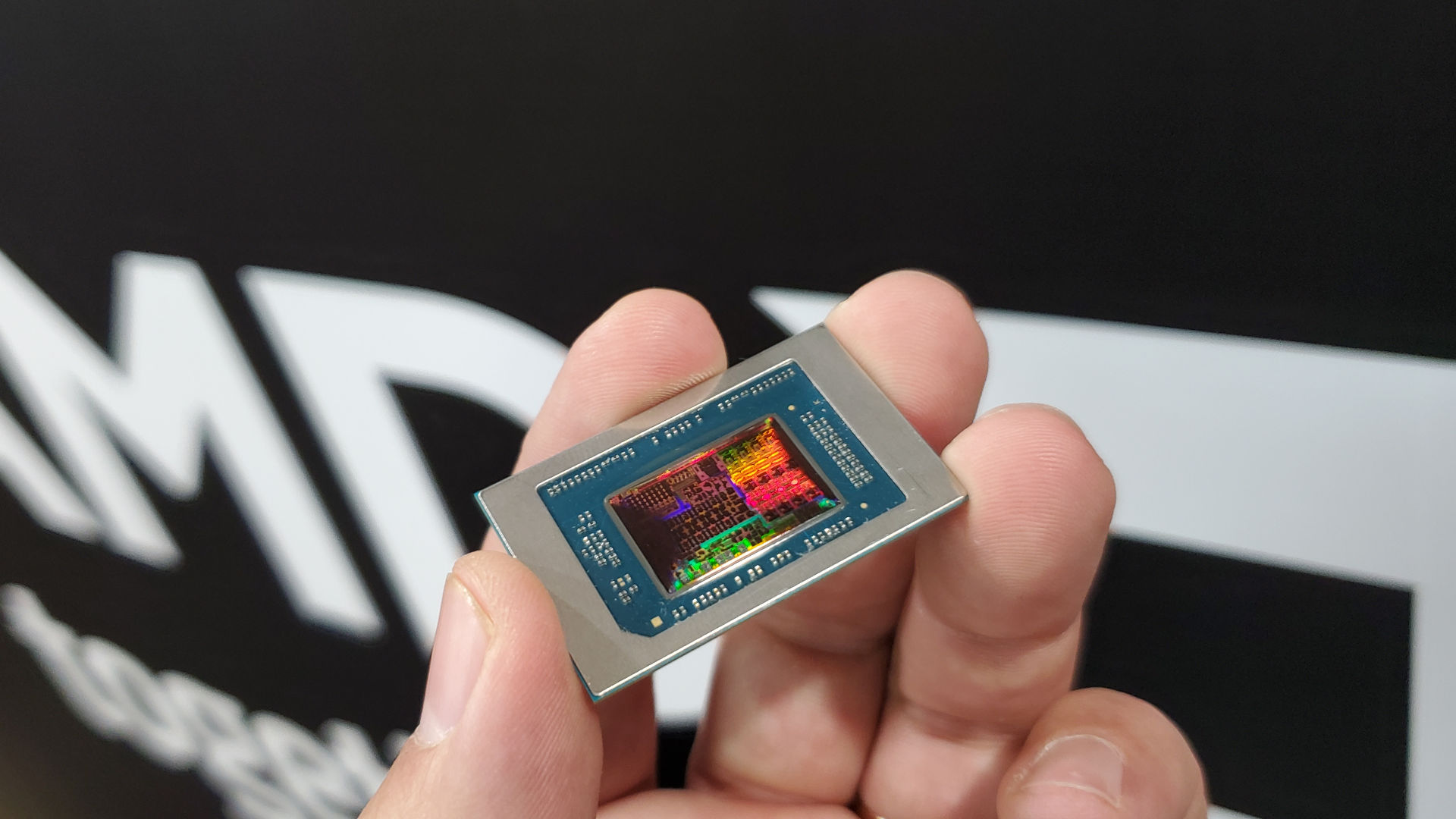

There are 12 cores in this chip but they’re not all the same as each other. (Image credit: AMD)

And that’s not the only change. Some early deep-dive tests of that chip design strongly suggest that AMD has tweaked the capabilities of the SIMD/vector units in APU’s cores compared to those expected for the desktop Zen 5 chips. At this stage, it’s not clear how (or if at all) AMD is managing the threads on these new APUs, as it’s clear that any being processed on the Zen 5c cores will not be processed as quickly as those on the normal cores—lower clocks and less L3 cache, shared across a greater number of cores, is only going to slow things down a bit.

Early benchmarks suggest that isn’t actually an issue (so perhaps AMD is doing some fancy thread management under the hood) but it does mean that Ryzen APUs in laptops are becoming increasingly more disparate, in terms of hardware and capabilities, than Ryzen CPUs in desktop PCs, which are made up of only one type of core, Zen 5.

The die space and power budget for the NPU could have been put to better use

Is that a bad thing? Well, one can argue that, so far, this just seems to be the case for AMD’s new APUs and the high-end laptop processors could well just be like the current Ryzen 9 7945HX—essentially a Ryzen 9 7950X but with lower clocks and a much lower power limit.

Intel has a full gamut of different architecture designs for its laptop chips, from the hulking Raptor Lake-based models that are like the 7954HX, through to the current multi-tiled Meteor Lake Core Ultra range, and down to the nearly-here Lunar Lake chips for low-power, ultramobile platforms.

The Zen architecture, followed by the move from monolithic to chiplet manufacturing, saved AMD from eternal gloom. That sole core design could be applied everywhere in the processor market, from handheld PCs to massive server chips. Now it would seem that AMD is taking a leaf from Intel’s book and increasing the segmentation across its chip portfolio.

This could be a design born of necessity, of course, as it could well be the case that ‘normal’ Zen 5 cores just aren’t power efficient enough to be used in energy-limited applications, such as APUs in laptops. I say cores but I’m really talking about the whole CCX, the core complex, as one cannot leave L3 cache from the equation.

Also a very quick and rough layout of STX.Seems to be 2 CCXs with the 4 “big” cores having majority of the L3?Photo courtesy of @System360Cheese pic.twitter.com/vnwMrEYExtJune 3, 2024

As a reminder, the four Zen 5 cores in the Ryzen 9 AI 365 and 370HX share a total of 16 MB of L3 cache, akin to 4 MB apiece. However, the Zen 5c cores (six in the 365, eight in the 370HX) get just 8 MB and that will certainly impact performance. Less cache means fewer transistors, which ultimately means the whole CCX consumes less power.

Another aspect to the point of these design choices being a necessity is AI. The NPU (neural processing unit) in the Strix Point chip takes up no small degree of valuable die space and there’s an argument to be made that the die space and power budget for the NPU could have been put to better use—that ship has long sailed now, of course.

I’m pretty sure if it wasn’t present, though, then the new APUs could sport 12 full-fat Zen 5 cores with plenty of cache, purely from comparing how much space they take up compared to the NPU.

But what if all of this isn’t about power consumption or AI? What if it’s simply about increasing the portfolio segmentation between laptop and desktop processors? Now, I know what you’re thinking—there’s little to no overlap between these markets, as the vast bulk of purchases of laptops are not made by individuals who are stuck between considering getting a portable PC or a hulking big desktop.

Just imagine how awesome this would be with a big GPU inside. (Image credit: Future)

And it’s not like AMD is doing an Nvidia, where it uses the same model name for desktop and laptop GPUs, even though the latter are all at least one tier lower down. For example, laptops boasting an RTX 4090 aren’t sporting an AD102 inside them—it’s an AD103, the same chip used in RTX 4080 graphics cards. You are absolutely not getting 4090 desktop performance on a 4090 laptop.

(Image credit: Future)

Best gaming PC: The top pre-built machines.

Best gaming laptop: Great devices for mobile gaming.

One might criticise AMD’s Ryzen AI branding but at least it’s not giving its APUs the same name as its desktop chips. Nobody is ever going to confuse a Ryzen AI 9 370HX with a Ryzen 9 9950X, for example. Well, there’s always going to be somebody who doesn’t understand the difference but at least any confusion that does arise isn’t intentional.

I don’t think AMD is trying to deliberately make its new Ryzen APUs any less capable than desktop Ryzens, it’s just that this is the unfortunate side-effect of trying to keep chips as small and as energy efficient as possible, all while offering more cores than ever before, as well as riding along on the now-ubiquitous AI bandwagon.

Strix Point and Strix Halo look like they’re really good APUs, but it’s still a shame that we’ll probably never get to see one that’s a cross between something like a Ryzen 7 7800X3D and a Radeon RX 7700 XT.

That’d be an incredible APU, better than Halo Point, but its cost of manufacturing and power consumption means it’s unlikely to ever see the light of day. One can still dream, yes?