The studios behind these mega hits spent more than a decade iterating on their favorite design ideas until they went supernova.

Like many at PC Gamer, I’ve been enjoying a healthy amount of Helldiving the last two months. Whether I’m shoulders-deep in pulped bug biomass or cowering beneath a storm of automaton energy bolts, Helldivers 2 has been a refreshing surprise. I expected Helldivers 2 to be good, but not “unforeseeable appeal that knocks out back-end servers and leaves players in a weeks-long login purgatory” good—similar to how I couldn’t imagine Baldur’s Gate 3 consuming the entire gaming consciousness for the tail end of last year.

Helldivers 2 isn’t an anomaly. It’s the product of 13 years spent honing the craft of creating jolly, gratuitous meat grinders

While Helldivers 2 and Baldur’s Gate 3 might look like sudden jackpot successes, they’re testaments to what can be achieved through continued, devoted iteration. They’re the products of development teams honing their collective craft across a decade or more. Arrowhead and Larian are studios who had the willingness—and all-too-rare freedom—to gamble on chasing a singular creative vision until the bet finally paid off, even if that sometimes meant risking bankruptcy.

Oh, and they held onto the devs making their games. That probably helps. Who knew?

Arrowhead: The house Magicka built

Developing the next surprise blockbuster is an easier problem to tackle if, like Arrowhead, you’ve basically been refining the same game since Obama was president. Helldivers 2 was a surprise to me, but it wouldn’t have been if I’d remembered that my history with Arrowhead games goes back more than a decade. Even though I’d played and loved it back in 2011, it took a casual mention from my editor to realize that, oh shit, these are the Magicka folks!

As I rotated the two very different-looking games in my mind, cubelike, their similarities crystallized. In hindsight, Magicka’s DNA is visibly threaded across everything Arrowhead’s made. Mid-combat key combos to combine elemental magic would evolve into the ordinance input sequences in Helldivers, producing the same slapstick carnage. Magicka’s farcical fantasy was a premonition of the Helldivers sci-fi satire. And when Arrowhead drifted from the Magicka model, it was still improving its art of gratuitous multiplayer action in the firefights of Showdown Effect and co-op dungeon crawling in Gauntlet.

Helldivers 2 isn’t an anomaly. It’s the product of 13 years spent honing the craft of creating jolly, gratuitous meat grinders where you punch in frantic button combinations to turn your foes and friends gleefully into mulch. The camera angle changed and now it’s orbital strikes instead of elemental spells, but Arrowhead’s been chipping away at the same block.

Larian: Ultima aspirations

Larian’s been in an even longer chase for its ideal game, dating back to its first fantasy release, Divine Divinity, in 2002. Each Larian RPG has been fueled by CEO and game director Swen Vincke’s long-maintained drive to recapture the wonder of playing Ultima 7 in 1992—of a fantasy world rich with potential interaction.

It wasn’t always a straight path. Shaped by the expectations of the era’s lingering Diablo 2 fever, Divine Divinity established an action RPG model that Larian’s fantasy games wouldn’t break from for years. Some of the studio’s diversions were self-inflicted, like the development of the “monster” that was 2009’s Divinity 2: Ego Draconis, where Larian—in Vincke’s own words—went “full monty and dived blindfolded into next-gen-console-development-hell.” But even Divinity 2’s troubled development had Larian tinkering toward some of what we’d see in BG3, with early versions of the dynamic, object-based interactions that have since become a pillar of Larian’s turn-based combat design.

While Larian’s path twisted, it inevitably bent back towards iterating on how best to build a rich, reactive fantasy sandbox, even when it meant risking the studio’s future. With debts piling in the wake of Divinity 2’s middling reception, Larian risked betting on outside investment, bank loans, and Kickstarter funding for the in-development Divinity: Original Sin, even downsizing its work on the concurrent development of Divinity: Dragon Commander to consolidate resources.

If the bet hadn’t paid off, Larian would have crumbled. But Original Sin wasn’t just a success. By staging a fantasy setting dense with potential interactions, the turn-based RPG was the closest Larian had come to claiming Ultima 7’s legacy, and it would provide the skills and budget needed to get even closer. The engine Larian built in-house for Original Sin was a vital foundation for iteration.

Original Sin’s reactive systems and storytelling craft were dramatically refined in Original Sin 2, ultimately forming the basis for the cinematic storytelling and remixed D&D 5E combat system in Baldur’s Gate 3 as it attempted to provide the open-ended possibility of a tabletop RPG session. It’s a clear lineage, down to BG3’s opening being a retuned echo of OS2’s first act.

Elevated arts

Keeping game devs around sure seems to help when you’re making games. Weird!

For both studios, those years spent pursuing the same creative visions meant that they could make the most of the major clear increases in production scale on their latest projects. They’d already had gold in their hands, but too few people could see its glimmer from an isometric camera angle.

Buoyed by a Sony publishing agreement, Arrowhead paired their 13 years of lighthearted co-op carnage chops with a higher graphical fidelity and third-person camera angle for the shooter-hungry masses—a combination that proved to be the catalyst for its explosive public reaction.

Thanks to the D&D license and Baldur’s Gate brand, Larian was able to supercharge the early access strategy it had proven with Original Sin 2. By the release of Baldur’s Gate 3, Larian was 10 times the size it was while making Divinity: Original Sin. Among the additions were cinematics teams that allowed Larian to meld its interaction-dense sandbox design with a greater depth of visual storytelling and motion captured character performances.

It’s hard to overstate that Larian and Arrowhead were in unique positions to maintain creative control over how to deploy those additional resources. Unlike many development studios—really, unlike most studios in their tier of production—Arrowhead and Larian are private, independently-owned operations. Bloomberg described Larian as a “unicorn” company: With CEO and creative director Swen Vincke as its majority shareholder, Larian’s strategy and goals are entirely self-determined, leaving the studio free to “make creative decisions on the game without having to compromise due to financial pressures.”

Arrowhead, while smaller, enjoys a similar freedom with founder Johan Pilestedt as its CEO and creative lead.

Strong rosters

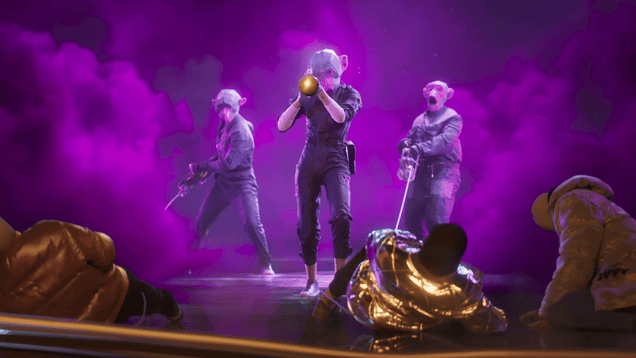

The Arrowhead team (Image credit: Arrowhead)

Members of Larian’s Dublin office (Image credit: Larian Studios)

One clear benefit of that self-direction, it seems, is employee retention. Chasing a hunch, I did a quick survey to see what I could find about each studio’s employment trends. The first thing I discovered: You can get your LinkedIn account suspended if you’re milling through game dev employment histories fast enough that the website thinks you’re illicit data-scraping software. Unfortunate. Exiled from LinkedIn, I turned to MobyGames to do some forensic credit research. And best I can tell, keeping game devs around sure seems to help when you’re making games. Weird!

Every person carried over from one project to the next can continue contributing to a studio’s collective craft. And judging from game credits, Arrowhead and Larian seem to have maintained a majority of their staff from one game to the next. Seven of the original 12 people credited as Arrowhead studio members on Magicka were also credited on The Showdown Effect in 2013. The trend continues into Gauntlet, then into Helldivers, and again into Helldivers 2, which carries over roughly 75% of the Arrowhead team members from the credits of the game before.

Larian games shows a similar trend since the studio’s near-bankruptcy to finish Divinity: Original Sin. Roughly 80% of Divinity: Original Sin 2’s credited studio staff reappear in the credits of Baldur’s Gate 3.

(Image credit: Future)

There are some asterisks here: Those percentage figures assume I was able to separate studio staff from contract employees and interns—a process that’s a little like reading tea leaves when, for example, “additional work” can be defined in any number of ways, depending on the studio’s convention. What’s less vague, however, is the fact that nearly every Larian employee who was first credited on Original Sin 2 and then on Baldur’s Gate 3 appears to have gotten a promotion along the way.

Those percentages stand stark against the backdrop of the ongoing devastation of game development layoffs—the latest dark chapter in an industry notorious for burnout, high turnover, and general career turmoil. A 2023 IATSE survey of games workers found that “less than half of respondents had made it to their seventh year in the business,” with two years being the most commonly reported career length. 42% of respondents described a lack of promotion opportunities at their workplace, with 37.9% of respondents characterizing working in games as unsustainable.

With their breakaway successes, Helldivers 2 and Baldur’s Gate 3 are testaments to what game developers can achieve when they have the ability to continue honing their craft. Of course, they can also leave you wondering: If more devs were given that chance, how many more of those successes would we see?