Took four years to build, but can it play Crysis?

Fed up with silly graphics card prices? Then build your own, including the GPU itself, the PCB, drivers the works. That sounds like a silly, perhaps impossible, notion given the complexity of modern graphics cards. Heck, even the might of Intel has struggled with many aspects of entering the GPU market with its new Arc cards.

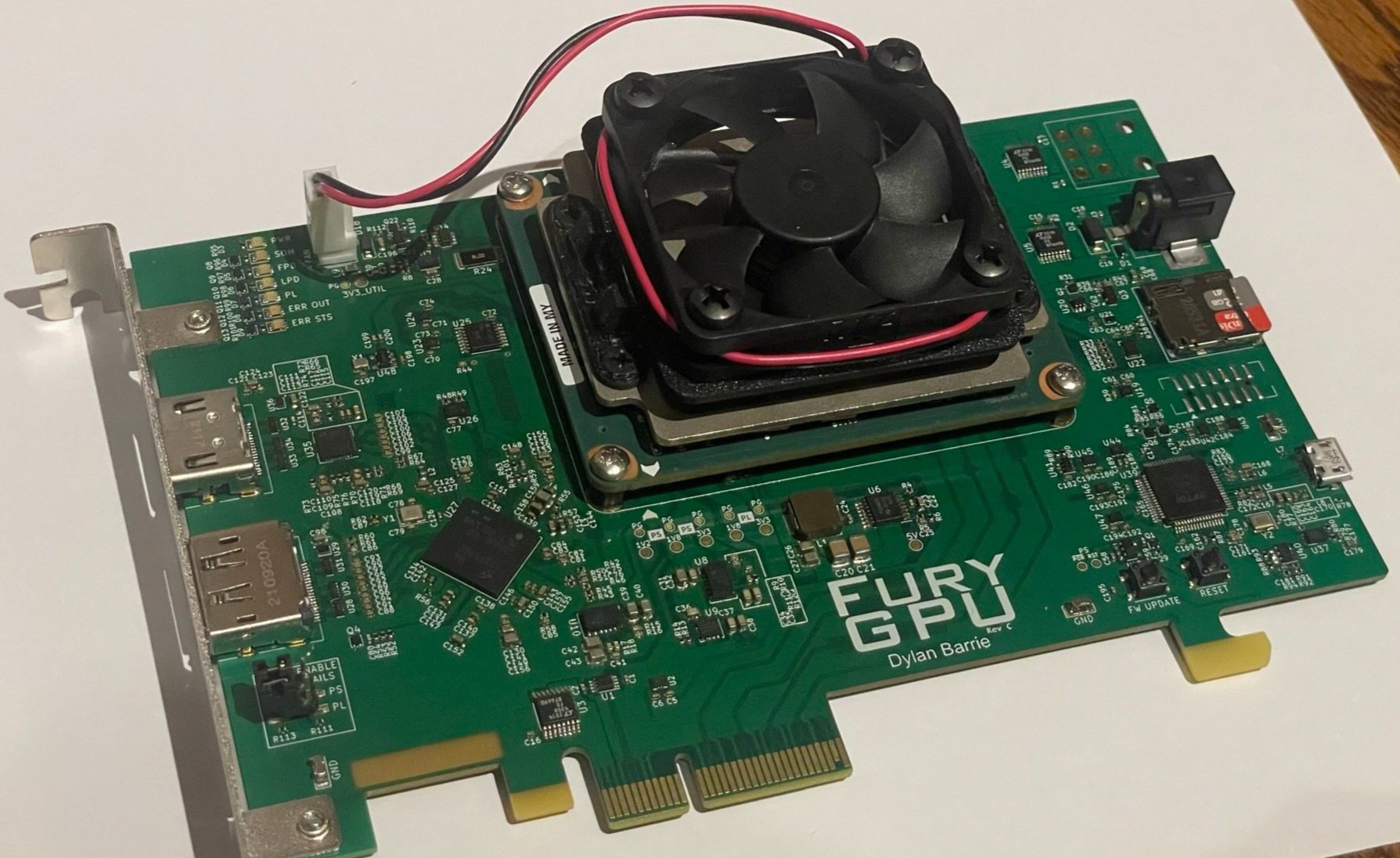

But that didn’t stop a software engineer, one Dylan Barrie, from making his own (via Tom’s Hardware). We give you the magnificent FuryGpu. It’s based on a Xilinx FPGA or Field Programmable Gate Array, which is basically a chip that can configured or programmed for specifics tasks. It’s a little like a blank silicon slate that can be reconfigured from a CPU to a GPU or anything in between.

There are pros and cons to FPGAs. They’ll never be as good as true dedicated silicon for specific tasks. But the offer far more flexibility than a dedicated design. Anyway, Barrie apparently spent four years developing FuryGpu and the result is a home-brew GPU with what he says is a roughly mid-90s feature set and the ability to run the original Quake at 720p and 60fps.

If you’re wondering about the specs, they go something like this:

Tile-based fixed-function rasterizerFour independent tile rasterizers400MHz GPU clock, 480MHz Texture Unit clockFull fp32 floating-point front-endTexture Units capable of performing linear and bilinear filtering on mip-mapped image samplesPCIe Gen 2×4 host interface

Not exactly an RTX 4090, then, but you trying making a GPU at home. Speaking of which, while the lay observer might imagine its the physical aspects of building your own GPU, working out how to turn a generic FPGA into a graphics chips, designing the PCB and so on, it turns out that it was in fact doing the Windows driver that was the most painful aspect for Barrie.

He also says clear opportunities for even better performance remain, all of which provides an intriguing insight into the difficulties Intel has had getting its driver quality up to speed. On the other hand, the fact that a one-man band can get a functional GPU up and running puts a rather different spin on the received wisdom that the barriers to entry are impossibly high in the graphics market.

(Image credit: Future)

Best CPU for gaming: The top chips from Intel and AMD.

Best gaming motherboard: The right boards.

Best graphics card: Your perfect pixel-pusher awaits.

Best SSD for gaming: Get into the game ahead of the rest.

That said, it did take Barrie four years and the result is about 30 years off the cutting edge. How many life times it would take to upgrade FuryGpu to today’s full ray-traced wonders, complete with support for AI-accelerated upscaling and frame generation doesn’t bear thinking about.

Barrie says he would like to make the entire project open source, though there are some legal issues that need to be addressed first. Even if that’s achieved, Barrie is at pains to emphasise that this project doesn’t have the makings of an Nvidia killer. “This is not going to change the GPU landscape or compete with any of the commercial players,” he says.

But we’re going to ignore that and blindly hope that it’s just the beginning of an upstart home-brew GPU movement that will force the likes of Nvidia and AMD to buck up their ideas, slash prices and sextuple VRAM allocations on their next-gen GPUs. You gotta dream, right?!