Taking notes has never been so much fun.

Pasokon Retro is our regular look back at the early years of Japanese PC gaming, encompassing everything from specialist ’80s computers to the happy days of Windows XP.

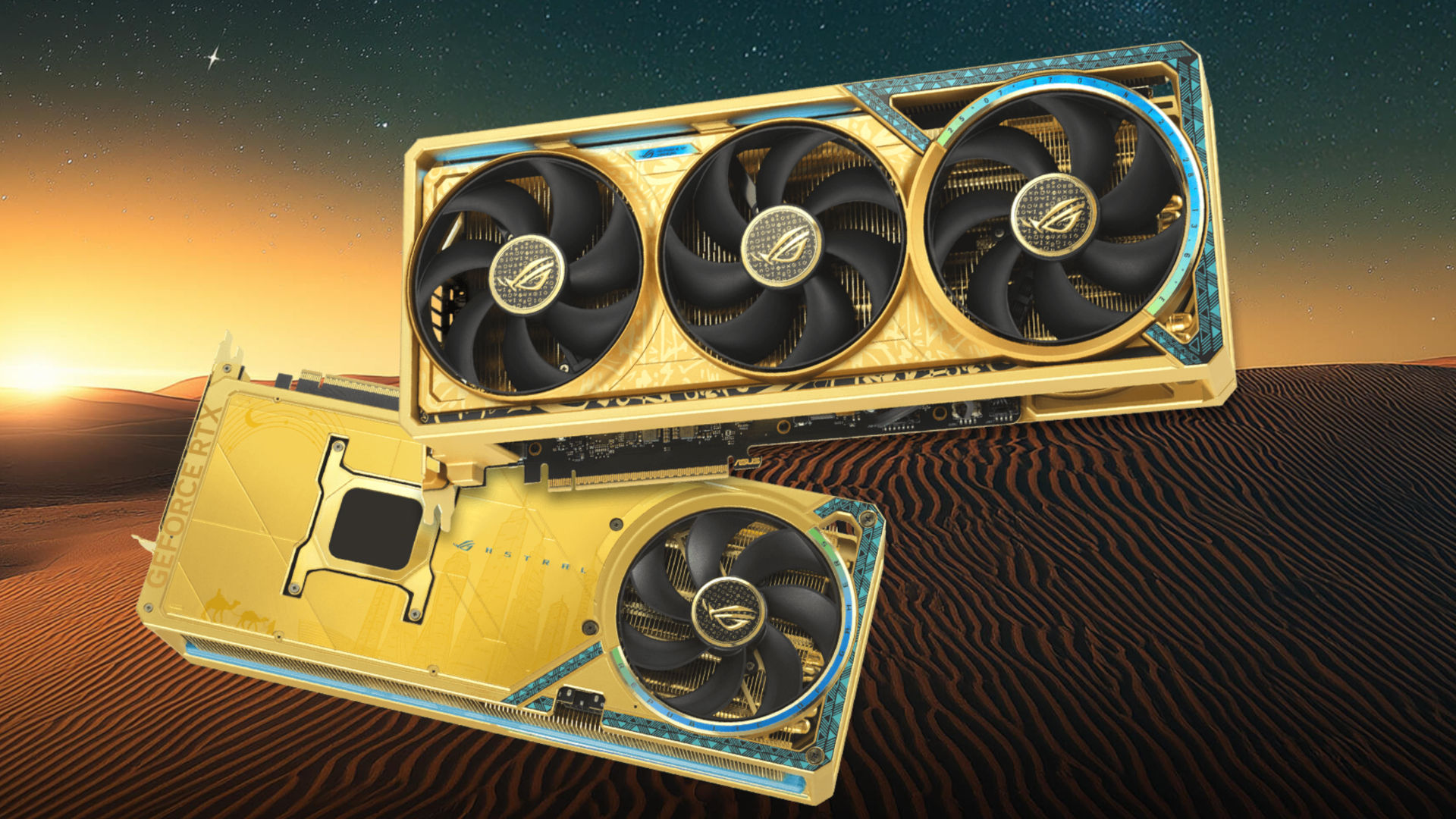

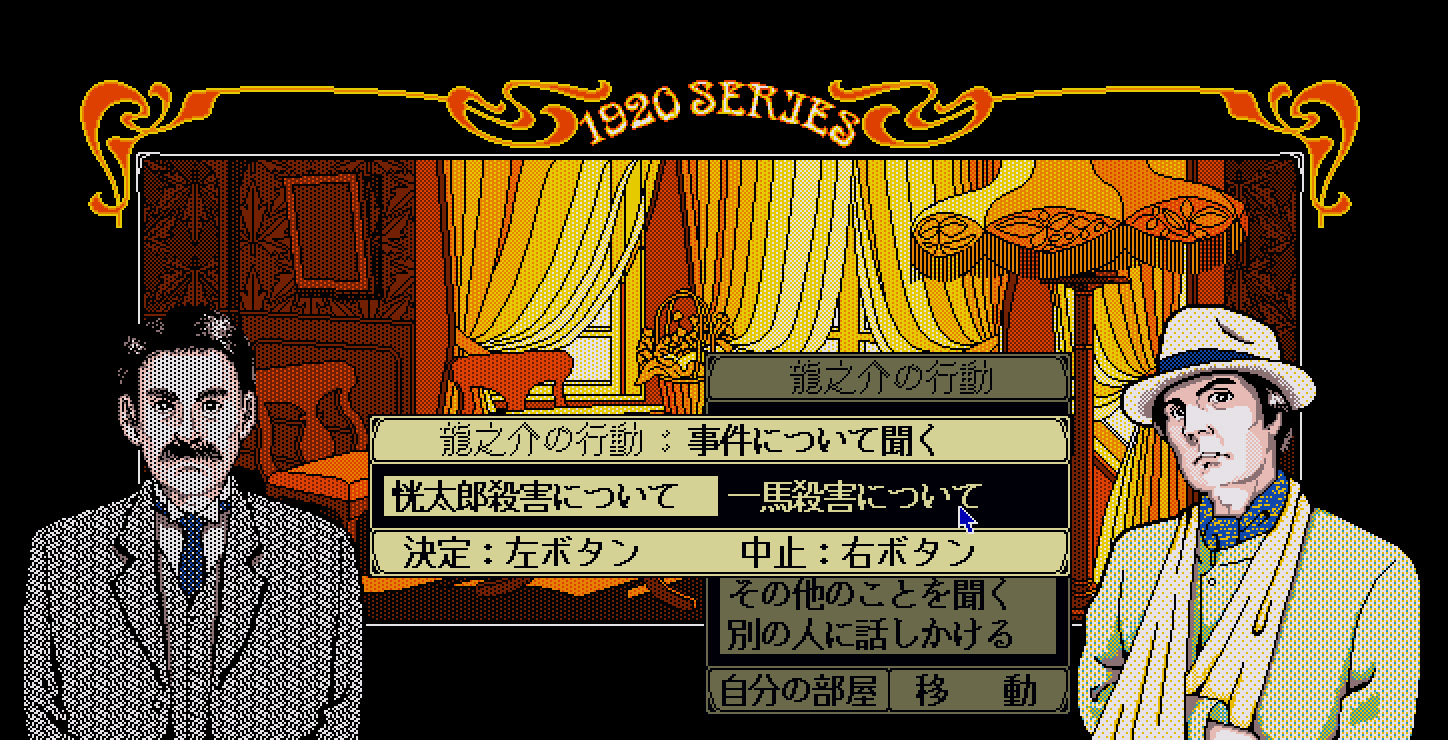

Developer: Riverhill Soft Released: 1988 PCs: PC-88, PC-98, X1 Turbo, X68000, FM77-AV, MSX2 (Image credit: Riverhill Soft)

A wealthy man has been murdered, and perceptive private investigator Ryunosuke Todo’s the only person in Japan capable of solving the mystery. More than a few people in the victim’s large family had a good enough reason to send him to an early grave—and it soon becomes clear that the killer’s not done yet. This 1988 adventure quickly spins a satisfying web of intrigue, although as much fun as pulling on Kohakuiro no Yuigon’s (“The Amber Will”) curious thread is, in this case the howdunnit is even more fascinating than the whodunit.

This game is the first entry of two in the “1920 Series” of murder mysteries, the second of which takes place on a cruise ship between Japan and San Francisco. As you’d expect from a name like “1920 Series,” a lot of effort has been spent trying to capture the mood and style of the time. Serpentine art deco embellishments are a regular feature, every member of the cast wears fashionable era-appropriate clothing, and the furnishings of each opulently decorated room believably reflect the roarin’ decade.

It’s enough to make your computer feel thoroughly underdressed, an RGB lit keyboard just not ritzy enough to display this world of smooth jazz and smoky bakelite.

The strong artistic bent even extends to the colour palette. As Todo approaches the Amber Mansion we see the front of the house rendered in ordinary, realistic, boring full colour. These tones are then replaced by slightly warmer tints as the view changes to show a close-up of the front porch. And then the instant you enter the house—the only location in the game—your screen’s bathed in deep sunset hues, reality only seeping back in if you look into the distance over the gardens. The amber-hued monotone used to create these gorgeous locations is not a technical limitation, but a conscious artistic choice. It’s a play on the game’s title and the mansion’s name, as well as a constant visual reminder that the dark events that have unfolded here have effectively trapped the building in amber, a small world existing outside the usual flow of time.

Out of time, but never out of your reach.

Inside the game’s unshelveably large plastic box is a personal organiser, and this little plastic folder is stuffed with page after page of custom-printed ringbound material designed to immerse you in the role of a fiercely intelligent independent investigator.

The first tabbed section contains a luxurious 19 page story leading up to the start of the game. Flip over to the back and you’ll find a replica of Todo’s business card neatly slotted into its bespoke plastic holder, as well as a manila-style envelope containing a few colour photographs showing period rooms and items. These bits and pieces don’t “do” anything—they’re not even used as old fashioned “type in word five on line two”-style copy protection—but they help to get you in the right frame of mind. You can almost hear Kohakuiro no Yuigon’s developer telling you not to rush, to sit a while and read a short story and only start the game when you’re ready.

Sandwiched between that scene-setting is a wealth of paper bursting with key information. There’s an annotated map of the house, fold-out family trees, and individual illustrated character pages with plenty of space for you to fill out pertinent information, or jot down anything else you feel might be relevant.

(Image credit: Kerry Brunskill)

(Image credit: Kerry Brunskill)

You really were expected to treat this organiser as a tool, not a cute prop to leave untouched in the box. It was considered so integral to the experience, every copy came with two printed tokens to cut out and mail off (along with 2,000 yen) if you needed spares.

In these enlightened times, as we download our games out of thin air and patches can be measured in gigabytes, it’s easy to view all of this paper-poking as nothing more than an awkward and expensive implementation of something now easily done on the screen. Convenient menus, reminders, personal annotations, and even hand-typed notes have been available in games for decades now (and Kohakuiro no Yuigon even includes a few itself), after all.

But it’s not so much the features as the physicality of these objects that matters. Being able to hold the organiser in your hands or slip it into a bag completely changes your relationship with the mystery.

(Image credit: Riverhill Soft)

(Image credit: Riverhill Soft)

(Image credit: Riverhill Soft)

(Image credit: Riverhill Soft)

(Image credit: Riverhill Soft)

(Image credit: Riverhill Soft)

Because you can pore over your own handwritten notes whenever you please, there’s a chance you’ll have a huge breakthrough over your morning coffee, or find yourself furiously writing down a flurry of new possibilities under the light of a bedside lamp. You can idly wonder if you missed a vital detail in the family tree and note your theory down in the margins, fold out the tarot sheet one more time and wonder if there’s a clue hidden in the artwork or meaning of the mysterious cards you acquire whale you play, or remove key suspect pages and pin them to the wall by your monitor, a tangible reminder of potential inconsistencies in someone’s statements or behaviour.

Kohakuiro no Yuigon is an engrossing and deeply stylish mystery filled with a rich cast of characters, a beautifully tangled tale packed with a tight knot of twists and turns just waiting for you to unravel them. It’s also something of a mixed media project, a deeply personal experience that gives you the freedom and the real-world equipment to approach this people-puzzle as you see fit.

Finding immersive and enjoyable ways to bridge the gap between the “analogue” player and the rigidly digital game they’re interacting with is a complex problem, but with this release Riverhill Soft proved that—at least under certain circumstances—you don’t even need to have a computer turned on to solve it.