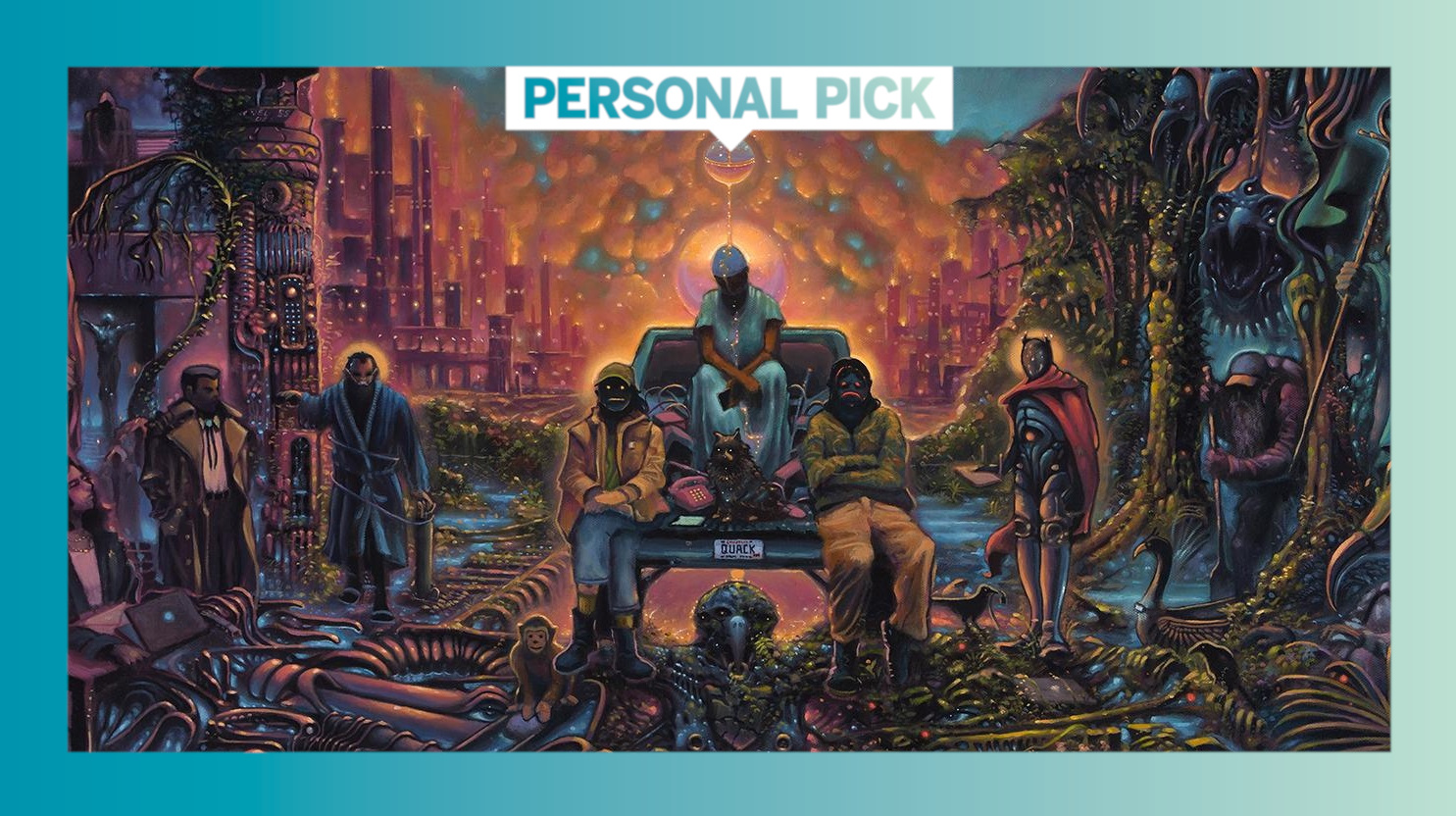

A standout adventure game in a red letter year for the genre.

(Image credit: Future)

In addition to our main Game of the Year Awards 2022, each member of the PC Gamer team is shining a spotlight on a game they loved this year. We’ll post new personal picks, alongside our main awards, throughout the rest of the month.

I’m really sorry everyone, but it’s the end of the year, we’re all cutting a little bit loose, and I think I deserve this: I want to begin this one with a quote. In Ursula K. Le Guin’s introduction to her novel The Left Hand of Darkness, she wrote “Science Fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive.” I don’t think I’ve felt that in a work of sci-fi more than with Geography of Robots’ miracle of a point and click adventure, Norco.

It’s the year 20XX or so and self-aware artificial intelligence has proliferated such that it’s a nuisance on the festering internet and a simple expectation of domestic labor and security-focused robots. Climate change has advanced unchecked, delivering at least one more Katrina-level disaster to New Orleans, and the United States is in the grips of some kind of low-grade civil war, “a meme that set Albuquerque on fire.”

At the same time, the only sense I get of this future is one of stasis, the same stifling, dehumanizing present we’re living in now extended for fifty years or so, with every potential moment of climax and resolution leading to more of the same. The Second American Civil War that lunatics like to jerk themselves off to has just led to some parts of the nation falling under the sway of “the soldiers of a popup junta,” while everywhere else you can still tell your phone to order someone making less than minimum wage to bring you a burger.

We might have just passed one such deferred resolution ourselves in the real world, potentially dating one aspect of Norco’s sci-fi prediction less than a year after it came out. As I write this, FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried has been arrested in the Bahamas (eat your heart out “Scrappy Doo found dead in Miami”) and mainstream celebrities who had been publicly shilling for cryptocurrencies in the first half of the year are just kinda shuffling their feet and refusing to make eye contact with you.

Nothing substantial is going to change—a lot of the same genre of tech fabulist guys are now saying that text prompt entries read by algorithms that steal artists’ work are going to replace those same artists, and where tech fabulists go, venture capitalists follow. Time will tell if we’ll only fail to learn our lesson on crypto in a wider sense or if we literally fail to learn our lesson from crypto and it comes roaring back.

For now, in late 2022, with cryptocurrencies facing public scorn and official inquiry, Norco’s running background gag skewering the tech so many years in the future already feels like a snapshot of a specific moment in the past, if in a charming and completely understandable way. It’s like stuff in the ’90s predicting that the internet would be cool and not just spy on you to sell you shit you already bought—they couldn’t have known.

The future refused to change

(Image credit: Geography of Robots)

New Orleans keeps getting destroyed in Norco’s world, but real estate money and fashionable young professionals “curating a theatrical self portrait of their lives in the ruins” roll back in like the tide and rebuild it, only slightly shittier, losing something in the process each time. Norco beautifully parallels that wider rebuilding and failed iteration in the recurring motif of protagonist Kay’s home flooding.

This was a regular occurrence for her growing up, but Norco ominously predicts that the next time will be the last. You get to witness that final flood during the climax of the game, going room to room in what is either a dream or a prophetic vision. You revisit the ghosts of Kay’s life, like her parents and de facto uncle, all directly or indirectly killed by the oil refinery that owns her home town.

At the risk of spoiling too much, you get a vision of the rest of Kay’s life after the events of the game, should she defy the will of its antagonist. That antagonist wants you to abandon the Body of Man, to use Kay to achieve some kind of technologically-infused religious apotheosis. You can instead choose to turn toward your remaining family and the people of this world, foiling the plan, at least for now. This would be my choice every time, and speaks to my most sincerely-held beliefs as to what matters in this life.

If Kay’s vision is to be believed, it doesn’t stick. She soon parts ways with her family and returns to the life of an alienated wanderer haunting “the overlit suburbs of the vast American limbo.” One final failure of revelation and resolution, stuff just stays the same while getting slightly worse.

(Image credit: Geography of Robots)

Norco’s a rich game, and you could dig into any aspect of it and turn up gold, like its references and parallels to early Christianity, the world building of its near future setting, or its meticulously researched portrayal of southern Louisiana that still, at the end of the day, comes straight from the heart thanks to its creators having actually lived there.

I come back to that feeling of hopelessness it evokes in me though. It hits on something very real about this time of material crisis and spiritual emptiness we live in, in a similar way to fellow adventure games Disco Elysium and Night in the Woods. Those games, however, end (or can end) on messages of hope and finding a way through thanks to the love of other people. “At the end of everything, hold on to anything,” Night in the Woods says. In Norco, at the end, there’s nothing left.