Somerville is a delightfully bizarre, physics-based puzzle adventure game that was developed by some of the former talent that created Playdead’s pair of modern classics: Limbo and Inside. And yet at the same time it plays very differently from those offerings, reminding me more of the seminal early-’90s classic Out of This World than Limbo or Inside with its upside-down setting, its color palette and character renderings, and its ever-rotating camera orientation from scene to scene. This was a pleasant surprise, though it isn’t nearly as polished or thought-provoking as its progenitors, leaving us with a very good game but ultimately not one I expect to be thinking about for very long now that I’ve finished it.

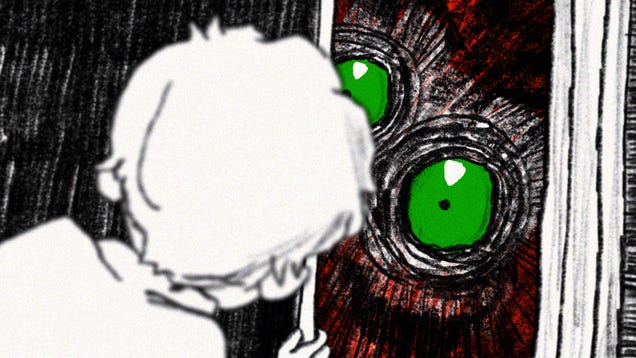

Somerville opens in the most wholesome way possible: A man, a woman, their infant child, and their dog are all on the living room couch, having fallen asleep in front of the TV. You take control of the man, who is never named. In fact, we never hear from him or from anyone else. Like Limbo, Inside, and Out of This World, there is no dialogue; Somerville’s storytelling is entirely visual. And visually, I do love what developer Jumpship has done here. Our nameless, voiceless hero is also essentially faceless, since all of these characters are more like impressionist renderings of people. And yet the use of color – and particularly contrast – makes the world pop when need be, such as when a dash of yellow wordlessly tells you that you can interact with an object.

Sound design, meanwhile, is effective in its minimalism. Aside from the piano soundtrack that’s good at nudging up the drama or tension when Somerville’s designers want it to, the pervading audio you’ll hear is the pained breathing and movement of our hero. Whatever happened to him clearly physically hurts him, and the further into this strange new world he gets, the more pain he’s in.

The use of color – and particularly contrast – makes the world pop when need be.

All of this paints a very dark, bleak, and yet intriguing mystery – one where the story wastes no time in ratcheting up the danger with extraterrestrial objects suddenly filling the sky outside of your remote cabin in the opening moments and, well, it only gets mesmerizingly weirder from there.

Somerville, then, is a slightly-under-four-hour quest to unravel what the hell just happened and is very much still happening. You’ll need to solve physics-based puzzles using your inexplicably glowing arm’s newfound power – primarily through turning the invading alien architecture into a permeable, water-like substance by shining light on it; specifically, light that’s been supercharged by your arm’s power. Extra layers get added to these powers as you progress, but it’s a bit thin; while it was enough gameplay to keep Somerville out of walking simulator territory, its puzzles aren’t likely to hold you up for more than a few moments at a time. In fact, the one time I did get hung up, it was more of an issue I had wrestling with the physics system than the actual game design.

Part of the reason its puzzles never get all that complex is that Somerville keeps its control scheme minimalist: the triggers and one face button are all you’ll ever need. I admire that simplicity – including in the way it keeps its interface nonexistent 99% of the time. Especially in a moody adventure like this, I love when the atmospheric world gets to shine through unobstructed.

An Imperfect World

As a dog lover I was delighted at first by the prospect of having a four-legged wingman, but sadly, your canine companion serves almost no purpose here aside from occasionally and subtly pointing you in the right direction. He doesn’t assist in puzzles or gameplay, he has no impact on the story, and you can’t even pet him at will. There’s value in some companionship in such a lonely world, but it seems like he could’ve been given something more to do.

Lonely and isolating as it may be, the altered Earth is, again, pretty. It’s also refreshing to be able to move about freely in each scene’s 3D space, which Somerville mixes up constantly. This is not a left-to-right stage progression; you’ll go up, down, left, and right at various times, and in that respect Somerville does a great job of staving off anything remotely resembling monotony during its short run. That’s a big part of where the aforementioned Out of This World reminder stems from, which was very much a good thing. And like that gem, I was always intrigued by where Somerville’s next scene might take me.

Occasionally, though, that freedom results in awkward transitions when you move from one room to the next. Sometimes the room you’re heading into will have a different camera angle that causes you to move in the opposite direction, right back where you just came from, which never ceases to be annoying.

I was always intrigued by where Somerville’s next scene might take me.

When I made it through, though, I found a conclusion to the story that left me with far more questions than answers as I watched the end credits roll, and I have to admit with some disappointment that I didn’t immediately feel compelled to gather around the nearest water cooler to discuss those questions with friends. It’s difficult to describe without spoiling anything, but I suppose I’d say that I didn’t find Somerville’s mystery as alluring as I’d hoped.