These under-celebrated adventure games hold up remarkably well more than 20 years later.

It’s time to drink deep from the well of ’90s adventure games, where 2D and early 3D art both benefited from the soft phosphor glow of our CRT screens. Where we really cared about hotkeys because the balls in our mice were caked with gunk. Where developers working in the shadow of LucasArts games like Grim Fandango were getting weird.

This is by no means an authoritative list of the most overlooked influential games from one of the wackiest periods in game experimentation, when FMV and 3D technology were respectively petering out and heating up. But they stood out then, and stand out even more today, in a new era of adventure games that seek to expand the historical limitations of the adventure genre.

1. The Best Within (1995)

Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Father is probably the best known of Jane Jensen’s beloved supernatural schattenjager (“shadow hunter”) adventure series. But its sequel, the gorgeous, ambitious The Beast Within—an FMV masterpiece that broke ground with its storytelling and incredibly detailed world—really set the bar for point-and-click adventures aimed squarely at adults.

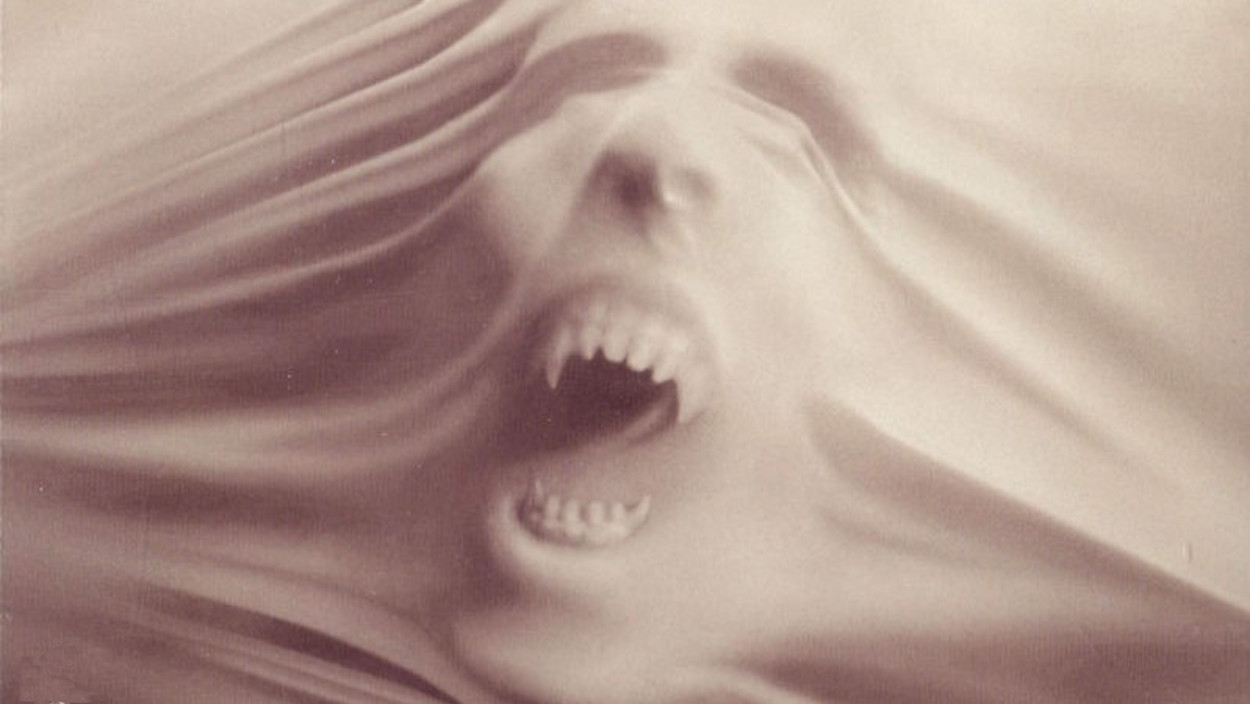

It came out in 1995, the same year as Roberta Williams’ FMV horror game Phantasmagoria, which, while also for older audiences, felt more like a novelty or object of fascination than something that had layers to slowly, patiently ponder and unpeel. Phantasmagoria also offered a much more contained narrative and a smaller, more intimate scope, with a story about a married couple’s isolation and paranoia in an ominous new home. And for that, it was fine. A little camp, a little cliched, set against the sort of memorably weird environments that defined 3D graphics at the time: plenty of over-the-top marble textures and slightly off-kilter architecture.

In almost direct opposition to this purposefully claustrophobic intimacy, The Beast Within went big. It covered multiple cities and towns. It tugged at the threads of a fictional Wagner opera that had been lost and cursed to the ages: barely realistic enough to feel plausible until you delve deeper into the supernatural chaos that make up the schattenjager’s bread and butter. Using real life locations also helped. There are scenes set in Munich, tourist spots around Bavaria, and, most dramatically, Neuschwanstein Castle (one ambitious fan even posted an account of his trip to Germany where he visited the game locations).

It was the first time that I’d seen a game pull together such a compelling, haunting world drawn from reality; to be fair, when I played this with my dad, I was also a kid and the closest combination of reality and gaming I’d experienced was playing Carmen Sandiego and The Lost Secret of the Rainforest. The Beast Within had such a wonderfully indulgent tone: you can tell Jensen loved working on the character dynamics between Gabriel and Baron von Glower, as well as Grace and Gerde; every single character in the ensemble cast was played to perfection.

I will never stop talking about this game, because playing it was like having an incendiary lightbulb go off—no, explode from sheer brightness—in my head, all those years ago. While everyone else was coasting, Jane Jensen was in a league of her own, and if Microsoft gives her the chance to rekindle the Gabriel Knight fire (she’s open to it!), it’ll be the best decision of their lives.

2. The Longest Journey (1999)

From a storytelling perspective, 1999’s The Longest Journey treads familiar ground in everyday fantasy magical realism—the idea of otherworldly forces seeping into a “normal” world—but it’s just so damn well made. Teen art student April Ryan, a relatively new arrival in the bustling metropolis of Newport, finds herself plagued by wild dreams about a fantastical place where dragons and magic are real. The story hinges on the idea of dual worlds—Stark devoted to order and science, and Arcadia to magic and chance—and the threat of a forced reunification, with April as a rather stereotypical “chosen one” to realign the all-important Balance.

Even over 20 years on, the environmental art is gorgeous evidence that photorealism often isn’t the best route when you’re trying to build out the character of a game world. The relationship between Arcadia and Stark isn’t just cosmetic, and the writing plays on this estranged sibling-type dynamic relationship to create compelling layers of tension and longing. The voice acting is excellent as well, down to April’s corny, self-aware one-liners that exemplify the finest cheese that adventure writing has to offer without going overboard.

The supporting characters, too, are all well-played and mostly well-formed. The Rolling Man is a fun specimen: April meets him as an “expat” from Stark who’s been living in Arcadia for the past fifteen years, in a ramshackle house he built into the cliff by the sea. He’s built around the very familiar (at least to me, as my home country Singapore has a large expat population) stereotype of the real-world western expat, who enjoys the distinction of being a stranger in a strange land while keeping an arm’s length from the populace. Cortez, April’s mentor, is an Arcadian expat in Stark, and chooses to maintain the core of his Arcadian principles through the role of being a weird old hippie that everyone finds a little creepy. And her landlords—a down-to-earth lesbian couple who run a boarding house for students and low-income arrivals to the city—evoke the most ’90s vibes of all.

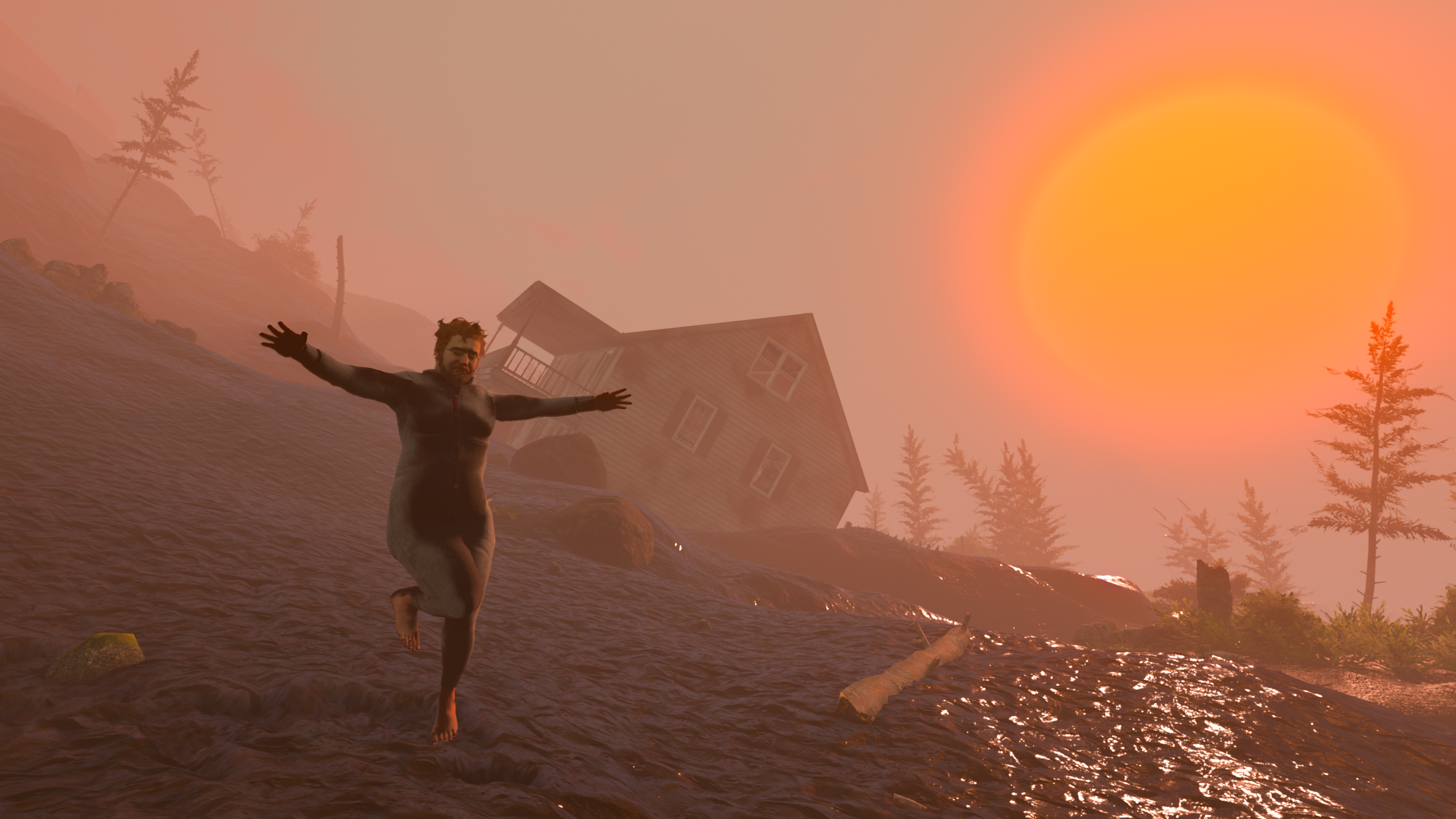

(Image credit: Funcom)

I can’t help but feel a sense of regret that I didn’t play The Longest Journey when it first came out, on a cozy CRT monitor where its thin, spidery cursive text font would have hit the mark (now it’s just borderline illegible). Its sense of scale is amazing. I never got frustrated having to schlep from one scene to the other because I wanted to absorb as much of the atmosphere as possible; I soaked up every last second of April’s small interactions with a weird old Arcadian sailor on the Marcurian pier. I pored through all the barely-intelligible fairytales and folklore and Arcadian history at the Enclave.

I even liked taking the Newport subway, for whatever reason—there’s nothing particularly special about it, but by the time I got my subway pass working, I was fully dialed into April’s journey and by god I was going to roleplay the living shit out of it.

This isn’t a story that reinvents the wheel: there are certainly some shit bits in there, like April’s edgelord housemate Zack, who doubtless only exists because ’90s storytelling felt compelled to remind us that date rapists are real. Even though writer Ragnar Tornquist was influenced by Joss Whedon, he actually made something that stands up better than anything Whedon did (whose success I feel was a testament to the talent and resilience of his crew). The Longest Journey had such a magnificent sense of immersion that still mostly holds up today, and was arguably one of the first “big” 3D games to take established fantasy and sci-fi tropes and make them feel engaging and new.

D2 (1999)

I’m always going to think of D not as shorthand for the most famous vampire in the world, but for “Dad.” I often think about D and D2 together (I haven’t played the middle child in the series, Enemy Zero) because I feel that what creator Kenji Eno did for the character of Laura was ahead of his time and a glorious finger in the face of an industry that largely banks on uniform continuity in franchises.

I’m not going to pretend that the first game, D, isn’t painful to sit through in the year 2022. It’s abysmally slow and the graphics look like crap on modern resolutions/screens, unless you can commit to putting yourself in the shoes of someone in 1995 who had never played an atmospheric horror game before. The awkward camera angles, the slow panning, the stiff, death-mask like faces were tethered to the technology available at the time. But where D really just let its freak flag fly was the way in which Eno forced his vision on the player—you only have two hours to play the game (there’s even a clock in your inventory to remind you of the time), and there is no save function. It was meant to be a meal eaten in one sitting, and you would have to eat all of it, or at least try to.

Eno wasn’t a perfect Michelin-starred chef, but his work was strange and engaging and just a little pretentious without being mind-numbingly overbearing, so much so that you’d definitely want to eat from him again.

With D2, released only on the Dreamcast, we meet Laura in a drastically different reincarnation but with the same “accessories;” namely the handheld compact that her mother left her, which gives you a limited number of in-game hints. The way that Eno envisioned his blonde, Lynchian protagonist as a “digital actress” was something that nobody else was doing in games, long before we got to the present and very exhausting era of digital humans. There’s a particularly cool blog entry on Laura as a fleeting fashion/cultural icon in Japan, modeling for Yojhi Yamamoto in an issue of HF magazine long before video game characters started showing up in Prada and Louis Vuitton shoots (high fashion brands are now, of course, all the rage in games like Fortnite and the metaverse-adjacent world).

(Image credit: Mobygames)

Laura’s influence aside, D2 stood out as a freakish experiment all on its own, with Eno going full-bore weirdo with a survival/action situation in the Canadian wilderness, complete with body horror, genetic engineering, cults, and angels. There is, unsurprisingly, a full 15-minute ending cinematic (this is part one) that seems to be, on some level, a partial reach for the epoch-spanning texture of 2001: A Space Odyssey, with some odd on-screen AIDS statistics and causes of death around the world.

It’s a lot.

But it was also fucking great, because it was like nothing I’d seen before. The little musical choices, especially, were such a great flourish, and inappropriate audio cues like cheery automated flight attendant reminders to buckle your seatbelt while you’re having a full-blown gunfight in a wrecked airplane. Eno had all the room to do what he wanted, and as this blog points out, his vision for D2 seemed more fully-formed than his previous two outings and closer to what he might have achieved in future games if not for his death in 2013.