Seeing things in the shadows.

Pasokon Retro is our regular look back at the early years of Japanese PC gaming, encompassing everything from specialist ’80s computers to the happy days of Windows XP.

I have never seen a game ratchet up the supernatural tension quite as effectively as Onryō Senki, an adventure game from 1988. Not Fatal Frame, not Devotion, not even my first trip to Silent Hill—none of them come close to matching the level of “I’m not scared I just want to sleep with the lights on for a week” horror found here. This is a game content to treat players like prey, something to be patiently stalked while it waits for the perfect time to strike.

Developer: Soft Studio Wing Released: 1988 Japanese PCs: PC-88/98, MSX (Image credit: Soft Studio Wing / Generation-MSX)

I’ve also never seen another game ship with a protective ofuda designed to ward off evil spirits like Onyro Senki; this clever packaging gives the PC-88 version’s warning about malicious ghosts being summoned forth if played without protection just a bit more weight. This small rectangle of printed paper is exactly the sort of straight-faced “No, really” caution a scary tale should start with: it’s a physical suggestion this story might not be quite as fictional as anyone playing expects it to be.

Onryō Senki begins with lead character Hiroyuki Kitahara—just some regular programmer working for a large national bank—attacked by demons while out walking on a peaceful moonlit night in the very ordinary city he calls home. The hospital insists his memories are just an unfortunate side effect of the shock caused by being attacked by stray dogs, a reasonable if dismissive attitude that ignites a desire in Kitahara to gather more evidence and uncover the truth behind his spooky encounter.

Onryō Senki takes the time to establish this baseline level of plausible deniability only so it can masterfully erode it over the following in-game days: An artist suddenly driven to painting disturbing pictures, a series of unnatural murders and mysterious “accidents,” a demon in the park that’s mildly surprised Kitahara can see it as it dines on dead dog.

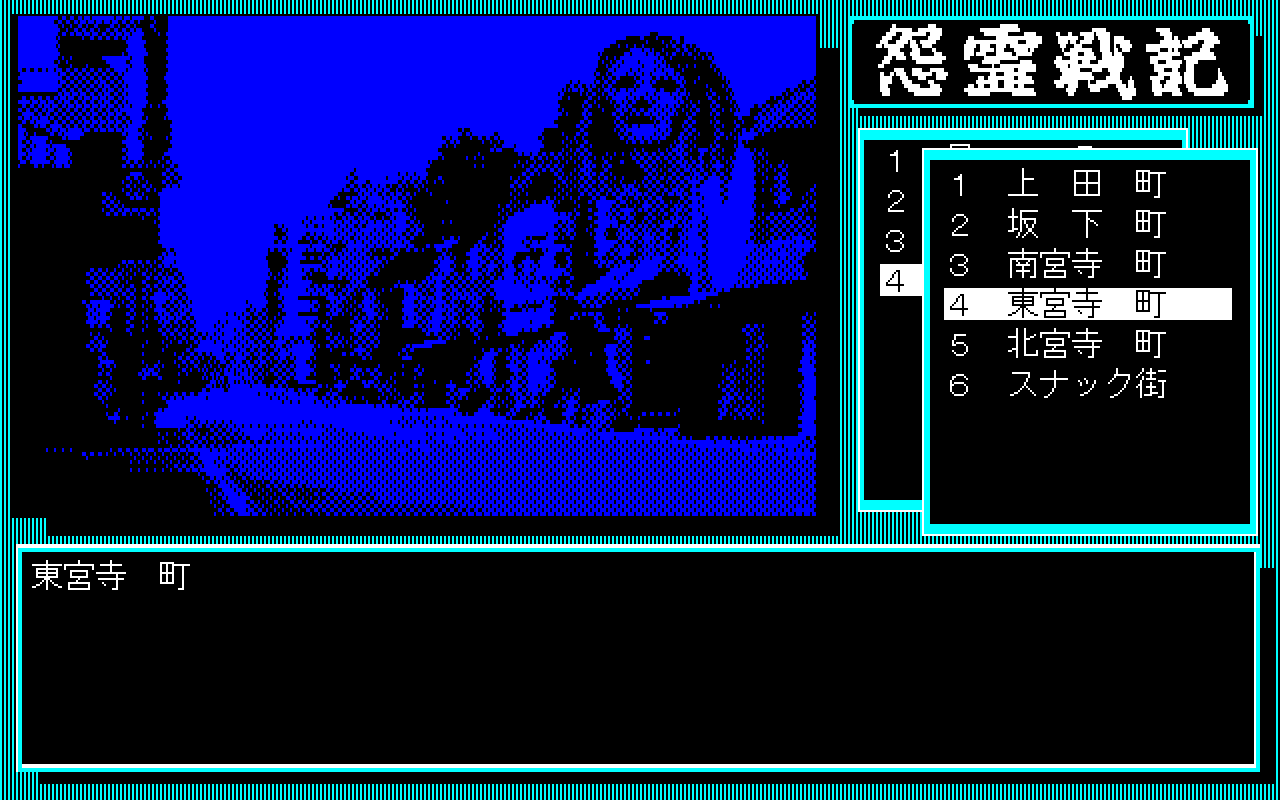

This is all happening in an adventure game stored on just a few floppy discs, controlled by simple commands picked from a text-based sidebar while a static picture of the scene sits in a neat little rectangle. The artwork is almost always heavily dithered and coloured using a striking combination of a midnight blue and stark black—detailed enough to resemble a specific place or scene, but always dreamlike and indistinct. It’s in many ways an early form of the shadows, fog, and film grain found in later horror games Visual noise is a natural hiding place for ghosts and ghouls.

Sound on

Kitahara’s desire to investigate the city’s burgeoning occult phenomena leads to him creating a program for the online-enabled computer terminal he has at home, which would’ve been seriously high-tech in the late ’80s. This seemingly benign bit of assistance is actually the perfect dread-enhancing tool, giving him (and me) access to a steady stream of reports about people who were officially attacked by “dogs” and “monkeys” as well as a map showing where the current ghostly hotspots are. Thanks to this information it’s easy to see the danger shifting and growing as the game progresses. More and more districts change from an uneventful blue to an ominous red as the ghostly threat spreads across the city.

The annotated map included in the manual helps to make sense of the short lists of place names available to choose from at each location. Kitahara’s fact-finding mission is split across both the day and night, with the daylight hours broadly intended for gathering information and the moonlit ones for acting on it. In the beginning ghosts appear at random during these wanderings only at night, a silent flicker of something so swift it’s hard to be sure there was ever anything there at all.

The initial subtlety of these hauntings is what makes them so effective—they’re not jump scares designed to make me scream but an independent otherworldly presence, a face in the background that definitely wasn’t there last time and refuses to appear again even if I try to force it to. The first time it happened I went back to the same area and… nothing. I checked my screenshots folder and… nope, I wasn’t fast enough to catch it, whatever “it” was. There’s not much as unsettling as a game making you question your own senses.

After a while it becomes clear these manifestations don’t “do” anything other than show up and then go away, and a brave player might start to look out for them just for fun… and it’s around about that point those “harmless” ghosts start hanging around—just present on the screen, watching—every one drawn in such a way it could be making direct eye contact with me.

(Image credit: Soft Studio Wing)

(Image credit: Soft Studio Wing)

(Image credit: Soft Studio Wing)

(Image credit: Soft Studio Wing)

(Image credit: Soft Studio Wing)

A disembodied head just sometimes manifests on the street right outside Kitahara’s home, staring straight out of the screen. There weren’t any ghosts that close to home before. Something’s changed. In these quiet moments in the dark it doesn’t feel like Kitahara’s alone: it feels like he’s vulnerable, and the dead are closely following his every move.

I catch myself wishing the world would unravel faster rather than putting me through any more of this excruciating slow-burn torment. The entire city is clearly teetering on the edge of a huge supernatural event but still not quite ready to topple over into the abyss.

The collapse of normality that does inevitably come is well worth the wait, and when Onryō Senki’s ghostly goings-on finally crosses the point of no return the spooky tapestry it has spent hours weaving unravels in a spectacular fashion. Ordinary people are attacked by ghosts in the street and sightings are no longer dismissed as angry wildlife, and it becomes so intense and undeniable that the police and the mayor officially get involved. Regular citizens rush to leave the city in fear. Skilled priests try to fight back and are decapitated on live TV in broad daylight. The good old days of creepy little sightings in the night and being afraid of the odd talkative demon feel quaint in comparison.

Kitahara can ward off evil spirits using special mantras and mudras, which are religious chants and hand gestures, but he’s nowhere near an all-powerful videogame protagonist. By the time he gets the hang of it the dead are able to violently manifest at will, turning the screen a threatening blood-red in the process. I’m not using these skills to bravely fight back against the afterlife, I’m giving myself just enough breathing room to safely get from one place to another as I scurry around the city looking for answers—and it’s clear I’m running out of time.

(Image credit: Soft Studio Wing)

(Image credit: Soft Studio Wing)

(Image credit: Soft Studio Wing)

Yet for all this apparent danger there are only a few places Kitahara can actually die in Onryō Senki, and they’re mostly avoidable with just a little thought and common sense. You’d think this relative safety would lessen the impact of the horror—so many horror games are based around monsters that can tear you apart in seconds. But Onryō Senki works differently.If anything Kitahara’ virtually guaranteed survival only intensifies everything happening around him.

There’s no easy way out for the player, no convenient excuse to put the game down for the day, no chance to become comfortably familiar with (or bored of) a scary scene through repetitive reloads. Instead there is only more and worse right to the end. Onryō Senki keeps on turning every shadow into a lurking spectre, every silence into a monster patiently holding its breath, making every event just that little bit more demonically shocking than the one before—until the credits roll.

Now where did I put that ofuda…?